If you’ve ever read an Agatha Christie novel, you will have encountered the poisons register, signed by anyone who bought poisons. It seems a sensible idea, but the register only came about after a law was passed in 1851 to regulate the sale of arsenic. What happened to force a change in the way people bought poisons, and why did the thought of regulations send Victorians into a tizzy?

Arsenic – more properly arsenic trioxide – is a highly poisonous white powder. It was very cheap, a by-product of metal industries, and ordinary Victorians could buy it from their local chemist, or even their grocer, as poison for rats and mice. It had little or no flavour – Robert Christison, daredevil toxicologist, had put some on his tongue, and discovered that it had a very slight sweet taste. Mix it in with gruel or stew, and the recipient would be none the wiser. The main symptoms of arsenic poisoning were vomiting and diarrhoea, which made it indistinguishable from the sometimes fatal bugs that often went the rounds in a country that had poor sanitation. Arsenic was a convenient secret weapon for poisoners.

Scientific innovation led to improvements in tests for arsenic in the 1830s and 1840s. In 1839, the first of the Rural Constabularies Acts was passed, which meant that professional county police forces started to appear. Perhaps there were more poisoners about, or perhaps they were now more likely to be caught.

Cases sprang up which the press seized upon. The most well-known was the trial of Madame Lafarge (pictured above) in France in the early 1840s, to whom any woman accused of poisoning would be compared. In Dickens’ magazine Household Words, the verb ‘Lafarged’ was used to describe someone having been done away with by poison. It gave the crime a Continental glamour, which had persisted since the time of the Borgias, even if it was perpetrated in an English hovel. Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor, a toxicologist who worked on many poisoning cases in the mid-nineteenth century, claimed that certain novels – such as Bulwer-Lytton’s Lucretia – were little more than a poisoners’ handbooks.

Professor Taylor had reason to complain. To give his work contemporary pizazz, Bulwer-Lytton (remembered now as a rather terrible author) had called his novel’s main character Lucretia Clavering. In 1846, the year Lucretia was published, a woman who lived in the Essex village of Clavering, Sarah Chesham, had been accused of no less than three poisonings. While Lucretia Borgia was a well-known Renaissance poisoner, Bulwer-Lytton was implying that the Victorians were just as good at creating their own. But Professor Taylor had worked on the Clavering cases: he had been sent the viscera of Sarah Chesham’s sons, and he had seen, inside the stomachs, the yellow smear which indicated the presence of arsenic trisulphide (what happens to arsenic trioxide after reacting with sulphur, released during decomposition). He had performed the chemical analysis which proved that it was, indeed, arsenic, taken in a huge quantity. He didn’t think Bulwer-Lytton took the reality of poisoning seriously enough, and that the novel dealt with its fatal theme too lightly.

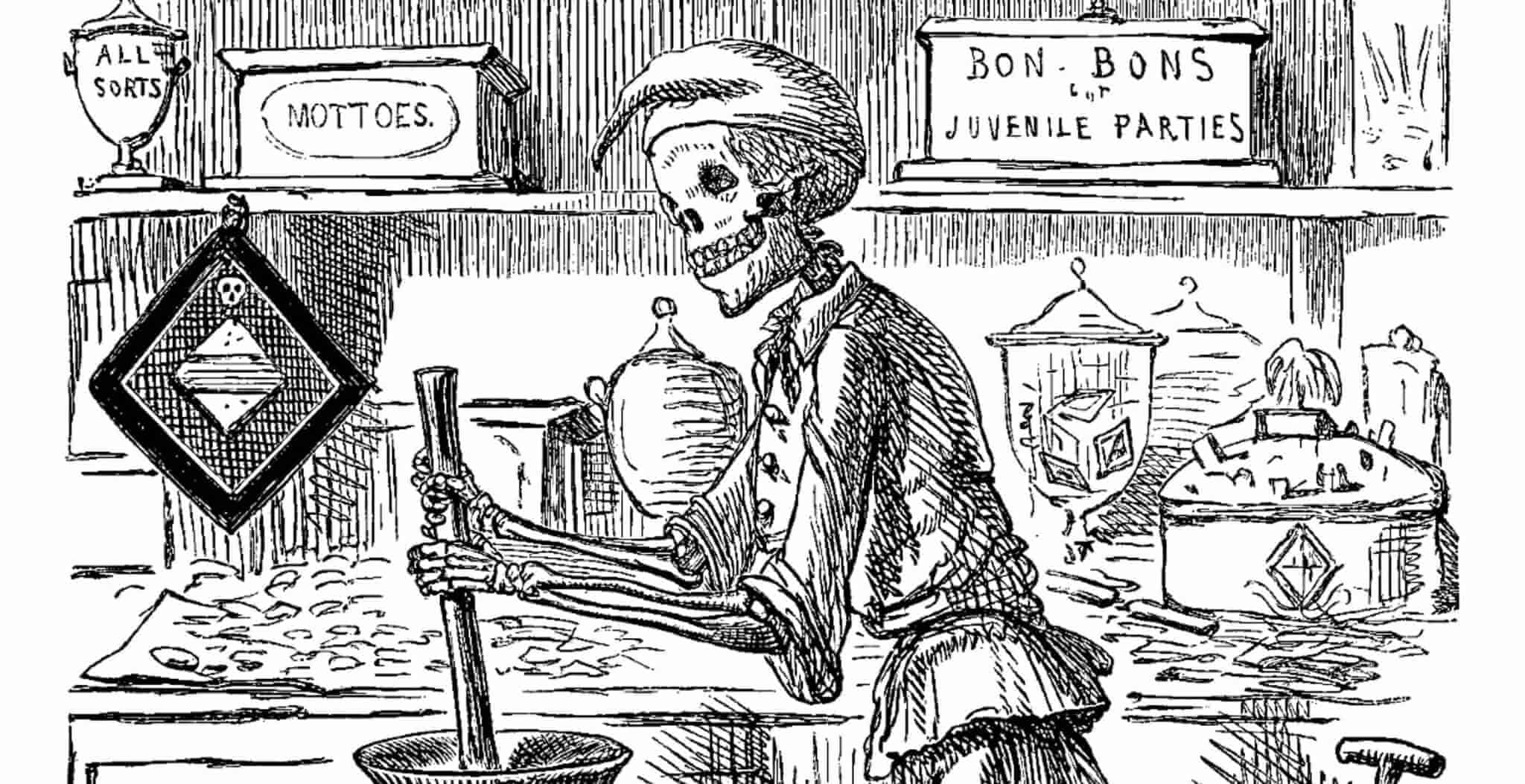

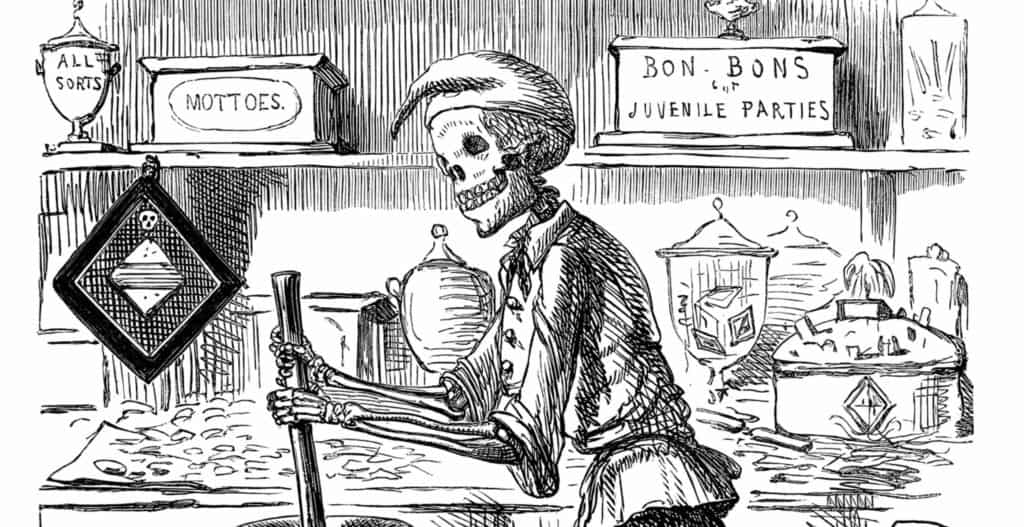

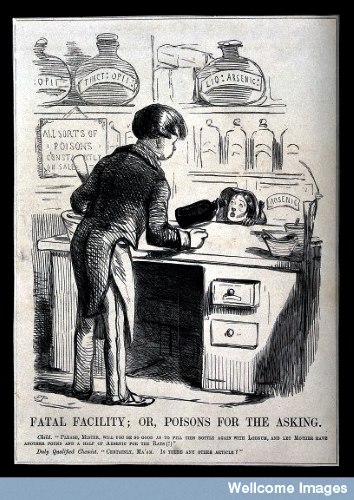

There were other cases of arsenic poisonings in Essex, far to the east of Clavering. The press claimed that all the cases were linked, as if women were conspiring en masse to kill. Elsewhere in Britain other arsenic deaths came to light, and at inquests and trials up and down the country, police, coroners, juries and judges were left to decide if they were murders or accidents. As arsenic was so easy to buy, it made the task even more difficult. Was there evidence that the accused had bought arsenic? They had to rely on the memory of the grocer or chemist or rat-catcher or post mistress – had they been approached by the accused to buy poison? And had they said what it was for?

With thanks to the Wellcome Library, London

A poisons register would clearly be the solution to this. It could then be proved if the accused, or an accomplice, or someone known to them, had bought arsenic. It might put off any would-be murderers. The idea was suggested at a meeting of medical gentlemen during the 1849 cholera epidemic; they couldn’t do much about rampaging disease, but it was time they controlled arsenic.

One thoughtful chemist in Millbrook, just outside Southampton, had stopped selling arsenic entirely. He thought it would prevent murders and dissuade suicides. If someone claimed they wanted it for killing rodents, he’d sell them nux vomica instead. It contains strychnine, but as the name suggests, nux vomica has a strong, bitter taste and induces nausea – only a tiny amount would raise suspicions, before harm was done. This didn’t stop 16-year-old William Bird from buying it from the Millbrook chemist in an attempt to poison his employers’ whole family on Boxing Day 1850. No motive was ever alleged. He’d already spent 18 months in prison for sheep-stealing and perhaps it was some slight – real or imagined – which set his heart against them.

The legitimate uses of arsenic were an argument against regulation. Farmers used it as a fungicide and steeped their seeds in it. Shepherds treated their sheep’s wool with it. Glass manufacturers made their glass clear with it, and shot makers used to it give their shot a spherical shape. It seems ridiculous, but arsenic was even used as food colouring, in Scheele’s Green Dye. This had occasionally tragic consequences; in 1848, one man died and several others fell ill after too much of it was used to colour a blancmange at a dinner in Northampton. It wasn’t just green fabric or green wallpaper that the Victorians had to be careful of. Arsenic was used in medicinal tonics, because in tiny amounts arsenic stimulates the blood – hence its use in leukemia treatments today. The thought of regulation was anathema to Victorians: personal liberty trumped everything. Why should it be limited just because some people were careless or murderous?

The government was under pressure from scientists and the press, so in 1851, the Sale of Arsenic Regulation Act passed into law. Some felt it had not gone far enough; what about all the other poisonous substances that weren’t regulated? Strychnine, cyanide, oil of vitriol…? The list was a long one, and was addressed by later legislation. The arguments ring true today: should popular entertainment glamorise crime? How far should governments impinge on personal freedoms for public safety?

When Agatha Christie worked as a pharmacist during World War One, she saw the poisons register first hand. Whenever someone signed it, her imagination wandered home with them: were they really going to kill the rats or purge their garden weeds?

Find out more about the arsenic poisoning cases in Essex in Helen Barrell’s new book Poison Panic: Arsenic Deaths in 1840s Essex, published by Pen & Sword in paperback. Her next book, Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor and the Dawn of Forensic Science, will be published in 2017.