It was 2015 and my first visit to Seattle – coffee central USA. Looking for somewhere to sit and enjoy my morning take-out, I chanced upon a small, narrow park sandwiched between Uptown and the waterfront. Perching on one of the many logs washed up on the shore, I gazed out over Puget Sound, the vast estuary that dominates not just Seattle but the entire region. Who or what was Puget, I wondered? It had a French ring to it. My phone came to the rescue. His name was Peter Puget, and although of French Huguenot ancestry, he was very much an Englishman. But I was more delighted to discover that he had spent his final years in Bath, my home city. This year marks the bicentenary of his death.

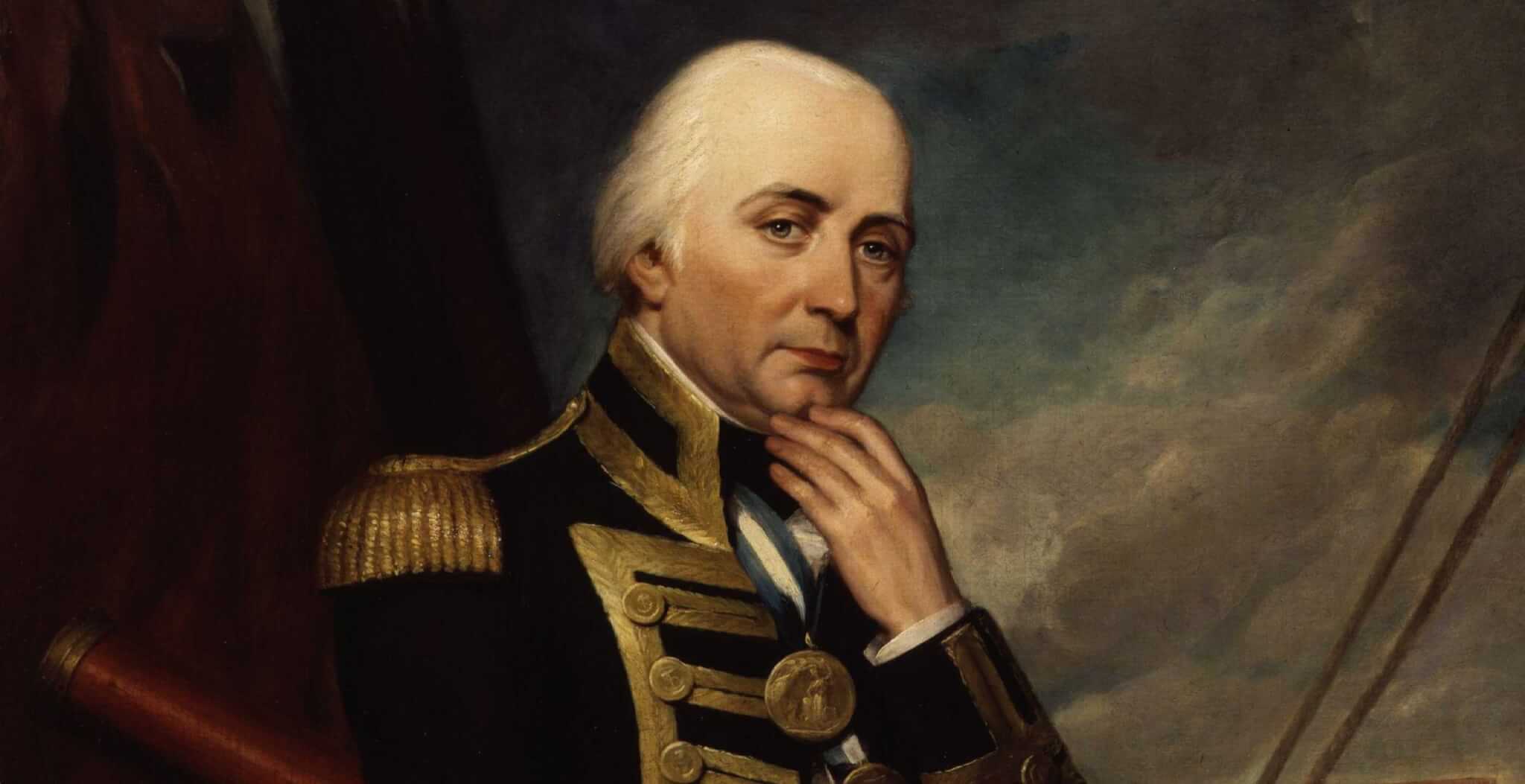

Puget was born in London in 1765 and joined the Royal Navy at twelve. In a distinguished career, this tireless and talented officer spent much of the next forty years either afloat or overseas, avoiding the extended periods at home on half-pay that dogged the careers of many naval officers.

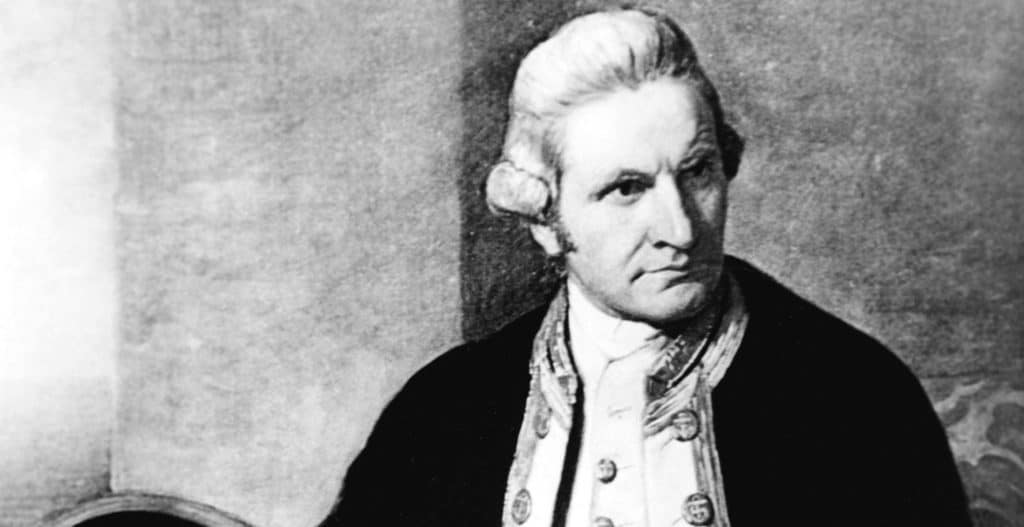

His geographical immortality resulted from his circumnavigation of the globe with Captain George Vancouver aboard HMS Discovery and her armed tender, HMS Chatham. Setting sail from Falmouth on 1st April 1791, the greater part of this four and a half year voyage was spent surveying the coastline of the Pacific Northwest. Charting such an extensive area provided Vancouver with numerous opportunities to exercise one of the perks of his position, that of naming places and features, and his junior officers, friends, and people of influence were to benefit.

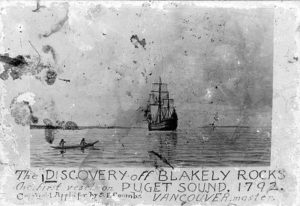

At the time, it was thought possible that Admiralty Inlet at the northern end of Puget Sound might lead to the legendary Northwest Passage. So, in May 1792, Vancouver dropped anchor off modern-day Seattle to investigate, dispatching Lieutenant Puget in charge of two small craft to survey to the south. Puget may not have found the Northwest Passage, but thanks to his captain, this vast body of water, plus Puget Island in the Columbia River and Cape Puget in Alaska, perpetuate his name.

Promoted to captain in 1797, he was the first captain of HMS Temeraire – years later “the Fighting Temeraire” of J. M. W. Turner fame. He went on to command three more ships of the line and played a decisive role during the Second Battle of Copenhagen in 1807.

In 1809, Puget was appointed a Commissioner of the Navy. This senior but administrative position ended his sea-going career. Nevertheless, in this new role, he became a key player in planning the unsuccessful Walcheren Expedition to the Netherlands later that year. Posted as Naval Commissioner to India in 1810, where he was based in Madras (now Chennai), he developed a reputation for fighting the corruption endemic in procuring naval supplies. He also planned and supervised the building of the first naval base in what is now Sri Lanka.

By 1817, his health broken, Commissioner Puget and his wife Hannah retired to Bath, where they lived in relative obscurity at 21 Grosvenor Place. Appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1819 and promoted to flag rank on Buggin’s turn in 1821, on his death the following year, the Bath Chronicle spared him less than a column inch:

Died on Thursday, at his house in Grosvenor-place

after a long and painful illness, Rear-Admiral Puget C.B.

This lamented officer had sailed round the world with the

late Captain Vancouver, had commanded various men-of-war, and

was many years commissioner at Madras, the climate of which

place greatly contributed to the destruction of his health.

Bath has long celebrated its noteworthy people. One of the more visible examples of this are the bronze plaques affixed to many houses to inform passers-by of notable former occupants – or in at least one case of a fleeting visitor. One evening in 1840, Charles Dickens accepted an invitation to dine at the home of the poet Walter Savage Landor at 35 St. James’s Square, returning after port and cigars to his room at the York House Hotel in George Street. Thanks to this isolated appearance at Landor’s dining table, the house sports plaques for both literary gentlemen, with Dickens’ plaque somewhat stretching the definition of the phrase “Here dwelt”.

But it’s no surprise that, despite Puget’s achievements, 21 Grosvenor Place is plaque-less. In contrast to his standing in the Pacific Northwest, Peter Puget remains almost unknown in his homeland. No known image of him survives.

Attempts by Seattle historians in the early twentieth century to discover Puget’s final resting place were unsuccessful. Their error, in part, was to assume he lay in grand repose in Bath Abbey or another of the city’s imposing churches.

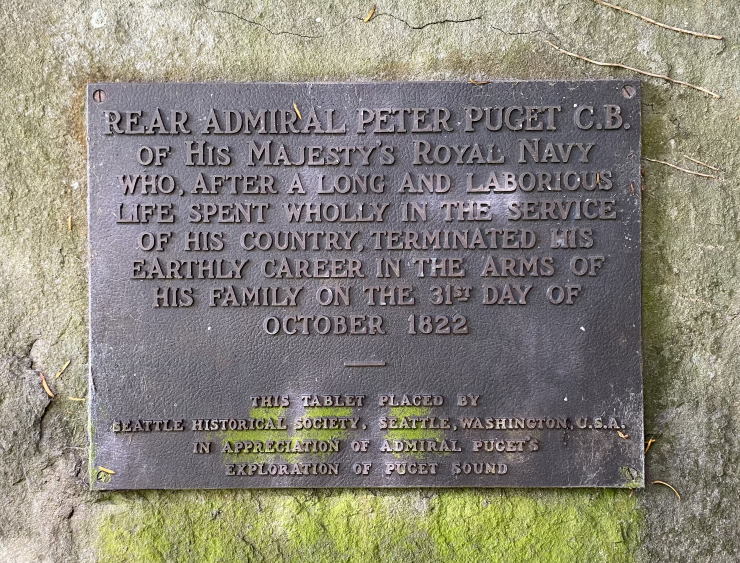

Fast forward to 1962, and Horace W. McCurdy, a wealthy shipbuilder and former president of the Seattle Historical Society, hit upon the simple idea of taking out a small ad in The Times requesting information on where Puget lay. Much to his surprise, he was successful. McCurdy received a letter from Mrs Kitty Champion of Woolley, a tiny village near Bath, confirming, “We have a Rear Admiral Puget buried in our churchyard”, and describing the tomb as “the shabbiest in the churchyard.” It remains so.

How Peter and Hannah Puget came to rest at All Saints Church, Woolley remains a mystery. Their monument, which can be found adjacent to the north wall, beneath a yew tree, is worn to the point that no trace remains of the original inscription. Yet, unlike 21 Grosvenor Place, the tomb boasts a bronze plaque thanks to the Seattle Historical Society. On a cold, grey spring day in 1965, over one hundred people crowded into Woolley churchyard to witness the plaque’s dedication by the Bishop of Bath and Wells. Also in attendance were representatives of both the Royal Navy and US Navy. I would like to think that Peter Puget looked on approvingly.

Perhaps, though, the essence of Puget’s indefatigable life is better captured by his original epitaph, which, thankfully, was recorded before it succumbed to the effects of time and the weather:

Adieu, my kindest husband father friend Adieu.

Your toil and pain and trouble are no more.

The tempest now may howl unheard by you

while ocean smite in vain the rocky shore.

Since grief and pain and sorrow still molest

the wandering vassals of the boundless deep

Ah! Happier thou now gone to endless rest

than those who still survive to err and weep.

Richard Lowes is a Bath-based amateur historian who takes a keen interest in the lives of accomplished people who have passed under history’s radar

Published: 17th August 2022.