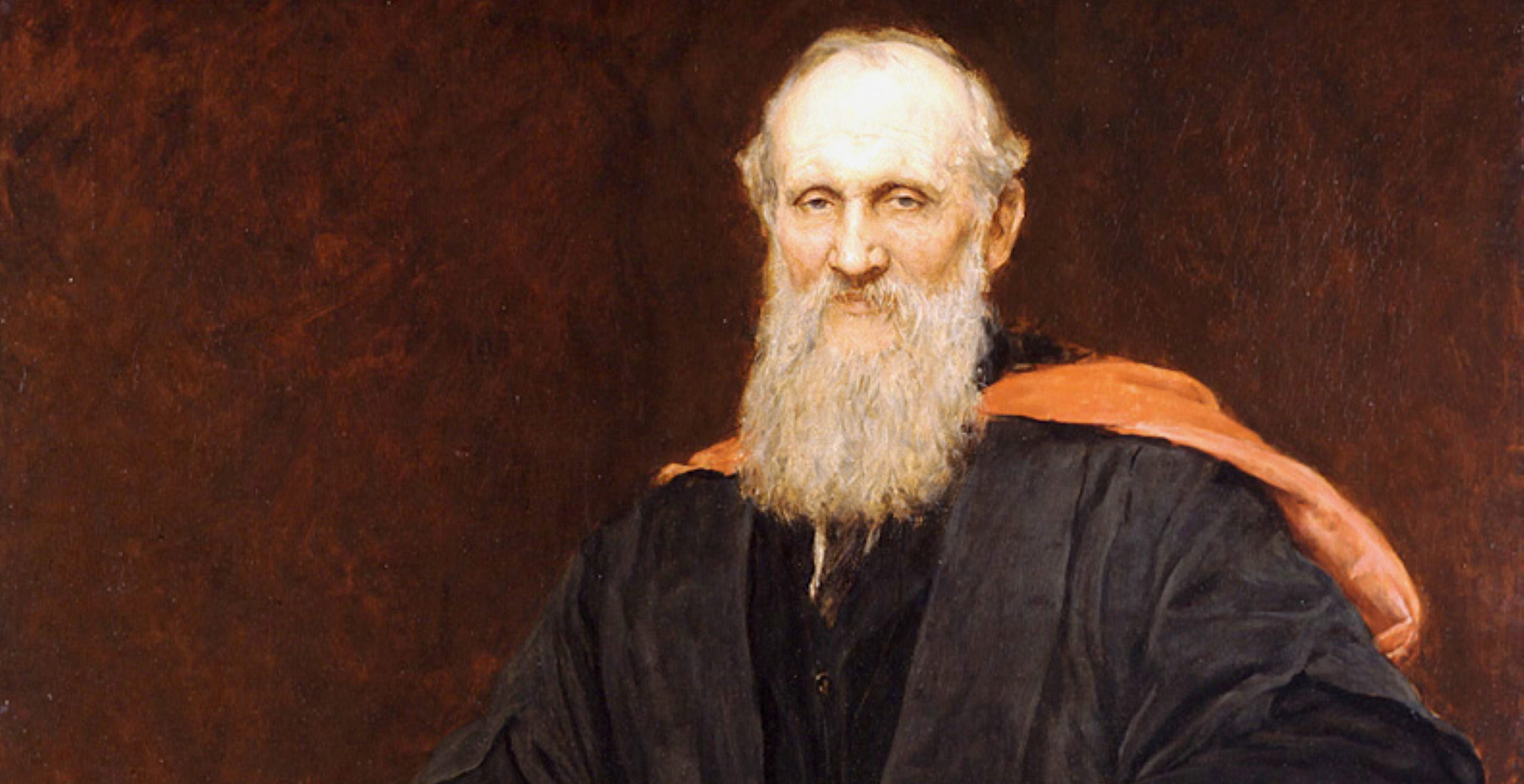

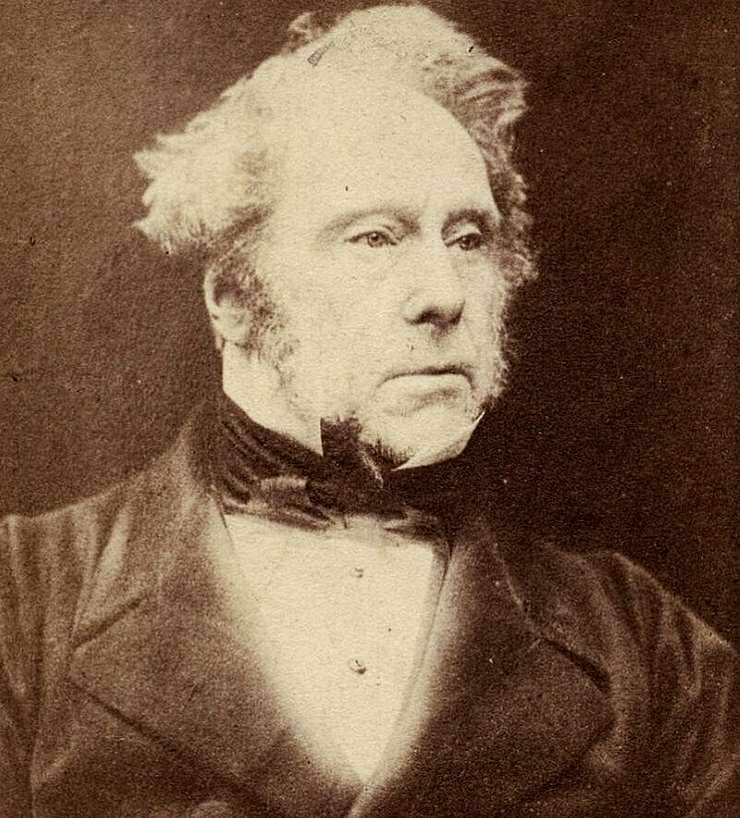

Born Henry John Temple, the 3rd Viscount Palmerston was an English politician who would become one of the longest serving members in government and finally become leader, serving as Prime Minister until his death in October 1865.

He was an English politician who served in various capacities throughout his long political career, including Foreign Secretary (hence Palmerston the cat who is currently residing at the Foreign Office!).

During his time in government he gained a reputation for his nationalist views, famously stating that the country had no permanent allies, only permanent interests. Palmerston was a leading figure in foreign policy at the height of Britain’s imperial ambitions for almost thirty years, and handled many great international crises at the time. So much so, many argue that Palmerston was one of the greatest Foreign Secretaries of all time.

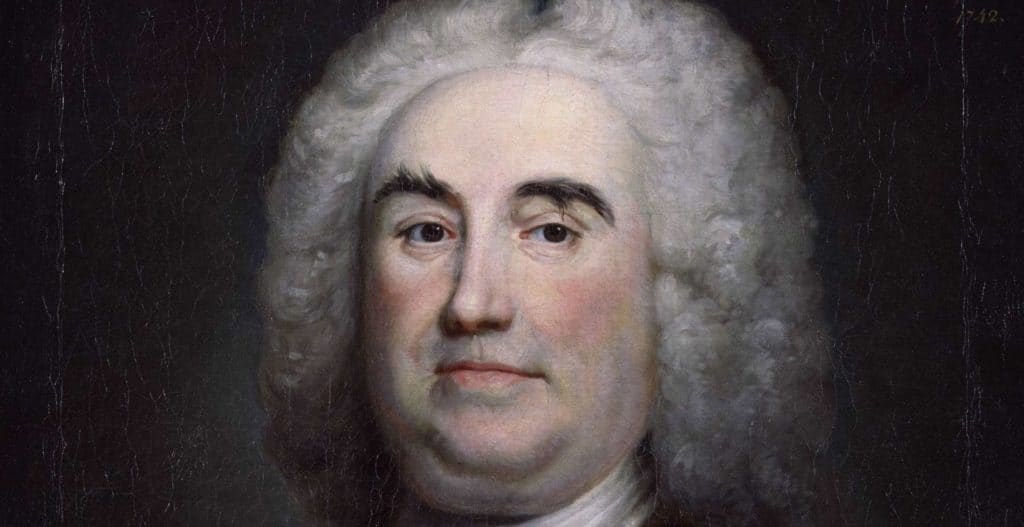

Henry Temple was born on 20th October 1784 into a wealthy Irish branch of the Temple family in Westminster. His father was 2nd Viscount Palmerston, an Anglo-Irish peer whilst his mother Mary was the daughter of a London merchant. Henry was subsequently christened at the ‘House of Commons church’ of St Margaret in Westminster, most apt for the young boy destined to become a politician.

In his youth he received a classic education based on French, Italian and some German, after spending time both in Italy and Switzerland as a young boy with his family. Henry then attended Harrow School in 1795 and later entered the University of Edinburgh where he studied political economy.

By 1802, before he had even turned eighteen, his father passed away, leaving behind his title and estates. This proved to be a large undertaking, with the country estate in the north of County Sligo and later, Classiebawn Castle which Henry added to his collection.

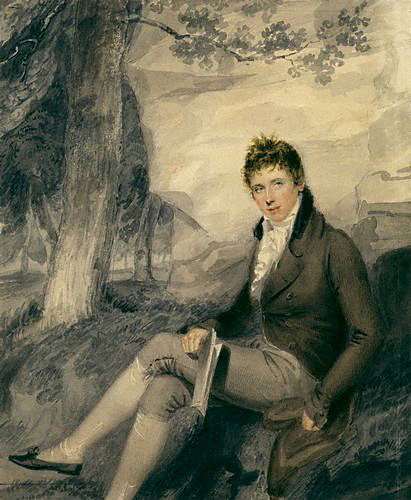

In the meantime however, the young Henry Temple, still a student but now known as 3rd Viscount Palmerston, would remain an undergraduate, attending the prestigious St John’s College in Cambridge the following year. Whilst he held the title of a nobleman he was no longer required to sit his exams in order to acquire his Masters, despite his requests to do so.

After having been defeated in his efforts to become elected for the University of Cambridge constituency, he persevered and eventually entered Parliament as a Tory MP for the borough of Newport on the Isle of Wight in June 1807.

Only a year into serving as an MP, Palmerston spoke out on foreign policy, particularly with regards to the mission of capturing and destroying the Danish navy. This was a direct result of attempts from Russia and Napoleon to build a naval alliance against Britain, using the navy in Denmark. Palmerston’s standpoint on this issue reflected his defiant, strong beliefs in self-preservation and protecting Britain against the enemy. This attitude would be replicated when he served as Foreign Secretary later in his career.

The speech given by Palmerston with regards to the Danish naval issue garnered a great deal of attention, particularly from Spencer Perceval who subsequently asked him to become Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1809. Palmerston however favoured another position – Secretary at War – which he assumed instead until 1828. This office was focused more exclusively with financing the international expeditions.

One of the most surprising experiences for Palmerston during this time was an attempt on his life by man called Lieutenant Davies who had a grievance regarding his pension. In a fit of rage he had subsequently shot Palmerston, who managed to escape with only a minor injury. That being said, once it had been established that Davies was mad, Palmerston in fact paid for his legal defence, despite almost being killed by the man!

Palmerston continued to serve in the Cabinet until 1828 when he resigned from Wellington’s government and made a move to the opposition. During this time he focused his energy strongly on foreign policy including attending meetings in Paris about the Greek War of Independence. By 1829 Palmerston had made his first official speech on foreign affairs; despite having no particular oratory flair, he managed to capture the mood of his audience, a skill he would continue to demonstrate.

By 1830 Palmerston had Whig party allegiance and became Foreign Secretary, a post he would hold for several years. In this time he belligerently dealt with foreign conflicts and threats which at times proved controversial and highlighted his tendency towards liberal interventionism. Nevertheless, no-one could have denied the degree of energy he exerted on a wide range of issues including the French and Belgian Revolutions.

His time as Foreign Secretary occurred during a tumultuous period of foreign unrest and therefore Palmerston took the approach of protecting Britain’s interest whilst simultaneously attempting to maintain an element of consistency in European affairs. He took a strong stance against France in the eastern Mediterranean, whilst he also sought an independent Belgium which he believed would ensure a more secure situation back home.

Meanwhile, he tried to resolve issues with Iberia by forming a treaty of pacification signed in London, 1834. The attitude he took when dealing with the respective nations was based largely on self-preservation and he was unashamedly blunt in his approach. Fear of causing offence was not on his radar and this extended to his differences with Queen Victoria herself and Prince Albert who held very differing opinions to him regarding Europe and foreign policy.

He remained outspoken, particularly against Russia and France in relation to their ambitions with the Ottoman Empire as he was greatly interested in diplomatic matters concerning the east of the continent.

Further afield, Palmerston was finding China’s new trade policies, which severed diplomatic contact and restricted trade under the Canton system, as directly in breach of his own principles on free trade. He therefore demand reforms from China but to no avail. The First Opium War ensued and culminated in the acquisition of Hong Kong as well as the Treaty of Nanjing which secured the use of five ports for world trade. Ultimately, Palmerston accomplished his main task of opening trade up with China despite criticism from his opponents who drew attention to the atrocity caused by the opium trade.

Palmerston’s engagement in foreign relations was well-received back in Britain amongst the people who appreciated his enthusiasm and patriotic stance. His skill at using propaganda to stir up passionate national feelings amongst the populace made others more concerned. More conservative individuals and the Queen regarded his impetuous and brash nature as more damaging to the nation than constructive.

Palmerston managed to maintain a great deal of popularity amongst the electorate who appreciated the patriotic approach. His next role however would be much closer to home, serving as Home Secretary in Aberdeen’s government. During this time he was instrumental in bringing about many important social reforms which were aimed at improving worker’s rights and guaranteeing pay.

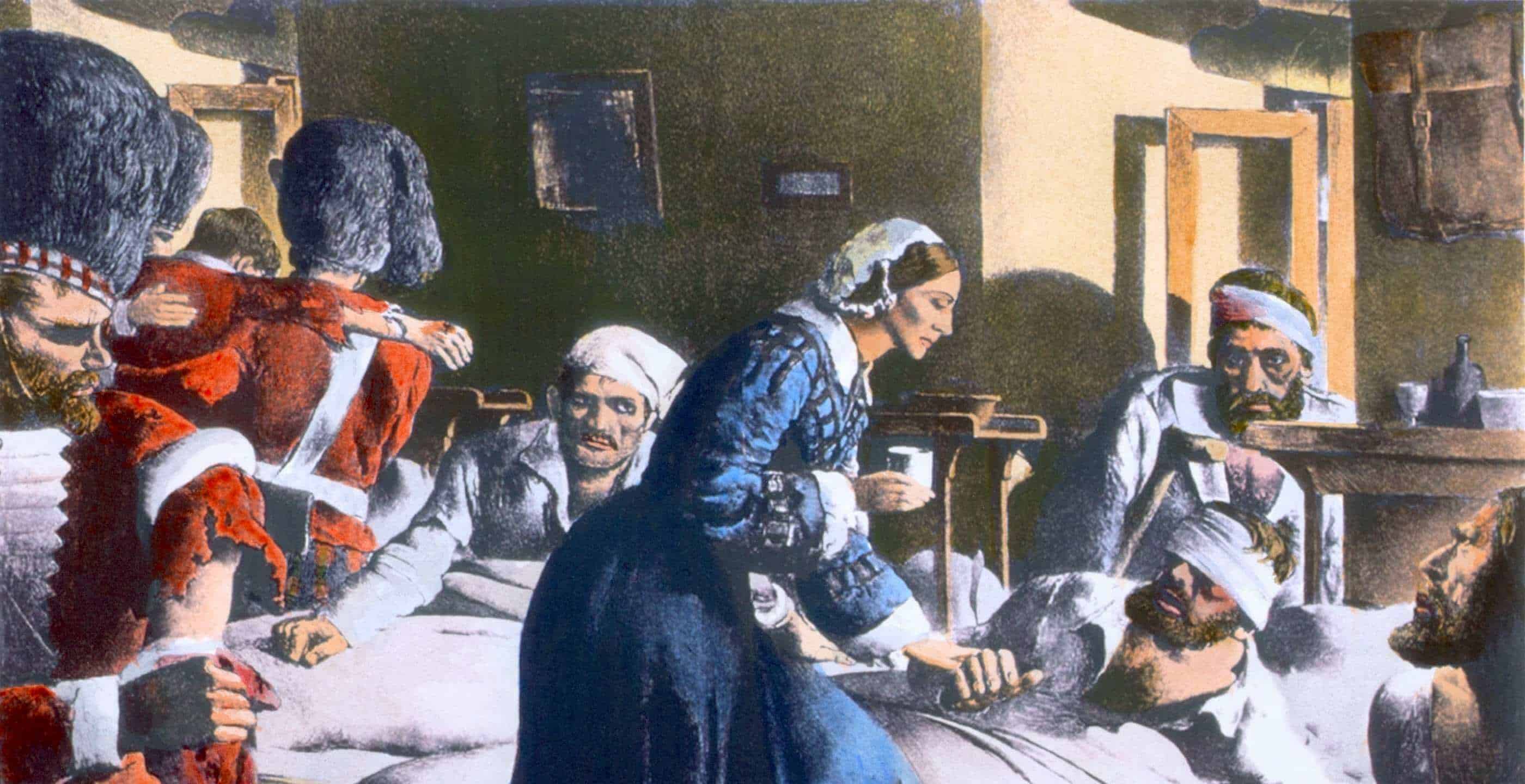

Finally in 1855, aged seventy, Palmerston became Prime Minister, the oldest person in British politics to have been appointed in this position for the first time. One of his first tasks included dealing with the mess of the Crimean War. Palmerston was able to secure his wish for a demilitarised Black Sea but could not achieve the Crimea being returned to the Ottomans. Nevertheless, peace was secured in a treaty signed in March 1856 and a month later Palmerston was appointed to the Order of the Garter by Queen Victoria.

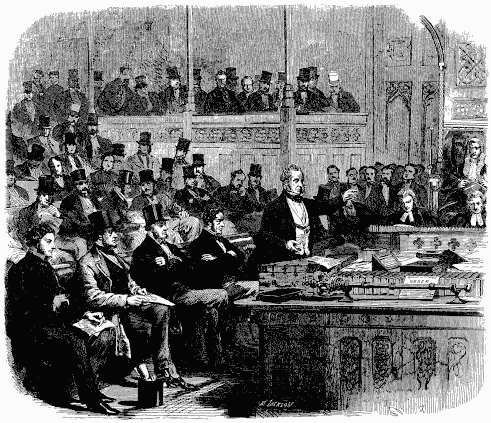

Palmerston during his time as Prime Minister was forced to evoke a strong patriotic spirit once more in 1856 when an incident in China was cited as having insulted the British flag. In a series of events Palmerston showed his unwavering support to the local British official Harry Parkes whilst in Parliament the likes of Gladstone and Cobden objected to his approach on moral grounds. This however did not have an impact on the popularity of Palmerston amongst the workers and proved to be a politically favourable formula for the next election. Indeed he was known as ‘Pam’ to his supporters.

In the years that followed, political infighting and international affairs would continue to dominate Palmerston’s time in office. He would end up resigning and then serving as Prime Minister again, this time as the first Liberal leader in 1859.

Whilst he maintained good health into his old age he was taken ill and died on 18th October 1865, only two days before his eighty first birthday. His last words were said to be “that’s Article 98; now go onto the next’. Typical for a man whose life was dominated by foreign affairs and who subsequently dominated foreign policy.

He was a remarkable figure, both polarising and patriotic, steadfast and uncompromising. His famous wit, reputation for womanising (The Times called him ‘Lord Cupid’) and his political will to serve, earned him favour and respect amongst the voters. His political peers were often less impressed, however no-one can deny he left an extraordinary imprint on British politics, society and further afield.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.