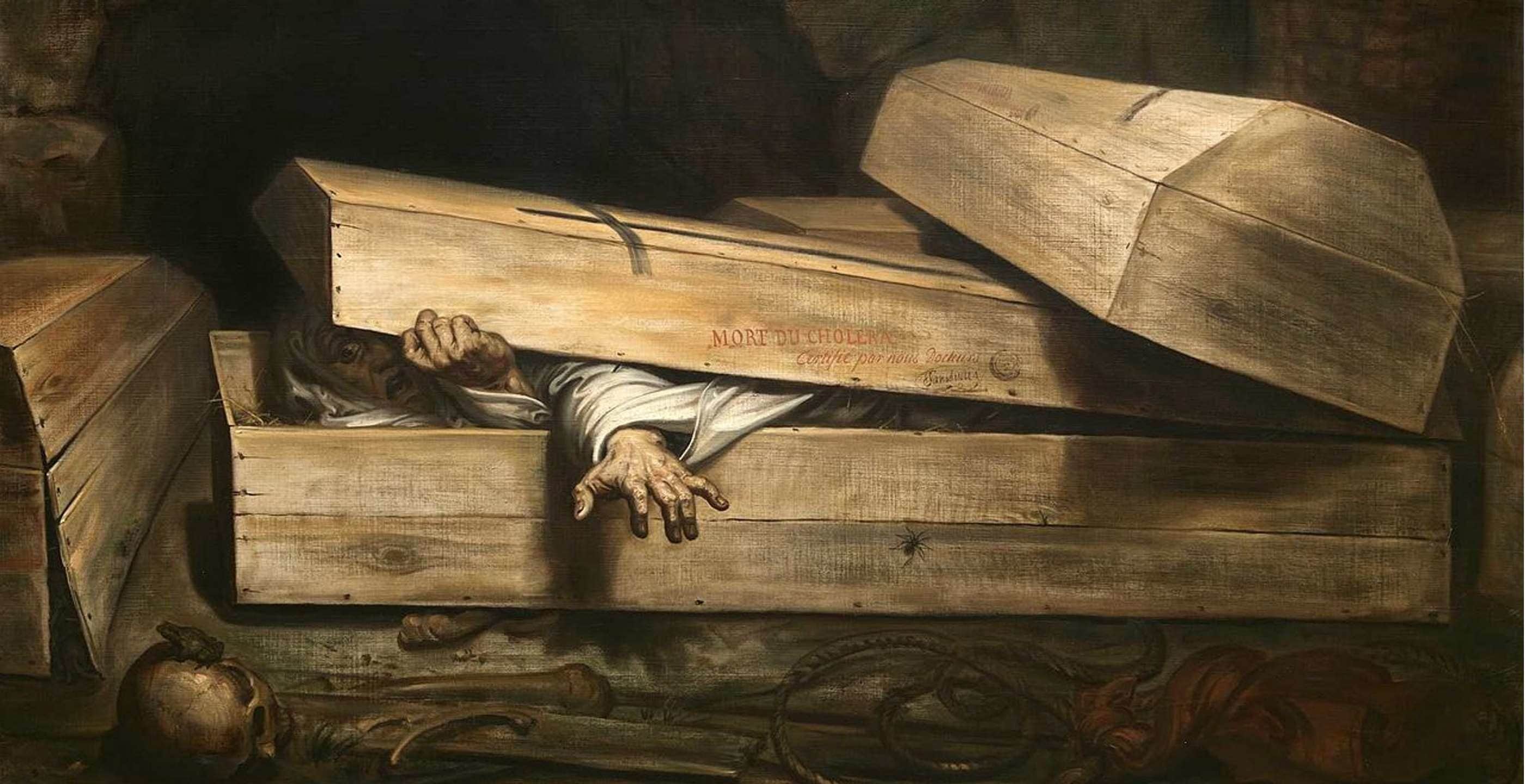

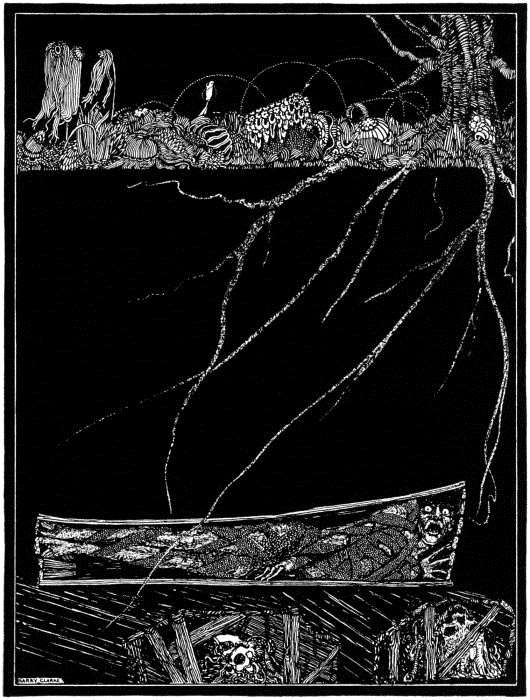

Taphophobia, the fear of being buried alive and waking up in one’s own grave, is the stuff of nightmares. It has provided the inspiration for some of the most cold-sweat inducing horror stories and films ever produced, including at least four tales by the master of the genre himself, Edgar Allan Poe.

Although phobias are technically “irrational fears”, until the 20th century the fear of being buried alive wasn’t irrational. Prior to the establishment of sound scientific means for identifying the point of death, the medical profession couldn’t always tell, particularly in the case of people in deep comas and those who had apparently drowned. In fact, one early resuscitation society was called The Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned (later the Royal Humane Society).

In the 19th century, there were several documented cases of individuals pronounced dead who were interred in family vaults only to wake up after the funeral party had left. Some stories were genuine, others legendary, such as that of Ann Hill Carter Lee, mother of General Robert E Lee who said to have been interred alive but was found in time by a sexton and restored to her family.

The fear was sufficiently widespread for societies such as the Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial to be established. Inventors created practical means of attracting attention should premature burial take place, the best-known contraption being that of the wonderfully named Count Karnice-Karnicki.

The count designed a spring-based system using a ball placed on the corpse’s chest that would automatically open a box on the surface to let in air if there was movement in the body. A bell would also ring and a flag begin to wave to attract attention to the grave, leading to the hair-raising possibility of people suffering heart attacks as a corpse began to wave at them. (“Coo-ee! Let me out!”)

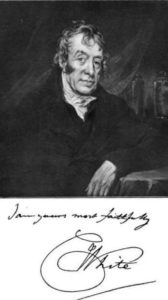

Hannah Beswick (1688 – 1758), a member of a wealthy family from Failsworth in Lancashire, was one of the people who had a pathological fear of premature burial; and with good reason, too. The funeral of her brother John had been about to take place in York when a member of the mourning party noticed his eyelids flickering, just before the lid was fastened down. The family doctor, Charles White, declared that John was still alive. John made a full recovery and lived on for years afterwards.

Unsurprisingly, this left Hannah with a morbid fear of the same thing happening to her. She asked her doctor (the same Charles White) to ensure that there was no risk of premature burial when her time came. It was a straightforward enough request, on the face of it; but Charles White had eccentricities of his own, and his subsequent actions would ensure that people would still be wrangling over Hannah’s will and testament a century later.

Charles White was a collector of curiosities who had already acquired the remains of a notorious highwayman, Thomas Higgins. He was also a student of one of the country’s leading anatomists and surgeons, the Scot William Hunter. White was not only personal doctor to the Beswick family, but also a pioneering obstetrician who was involved in the foundation of the Manchester Royal Infirmary.

Although there does not appear to have been any reference to embalming in Hannah’s will, White embalmed her body, probably using techniques which would have been familiar to him through studying with Hunter, who had devised them. The process involved arterial embalming by injecting turpentine and vermilion into the corpse’s veins and arteries. The organs were removed and washed in spirits of wine. As much blood as possible was squeezed from the body and more injections followed. Then the organs were replaced and the cavities packed with camphor, nitre and resin. The body was finally rubbed with “fragrant oils” and the box that contained it was filled with plaster of Paris to dry it out.

Once embalmed, there was of course no chance of Hannah returning to life, but she didn’t receive an appropriate funeral, either. Rumours were rife about whether a massive bequest had been made to White to embalm her (unlikely, since the details of the will apparently included reference to £100 for White plus a sum for funeral expenses). All Hannah had wanted, it appeared, was to ensure she wasn’t buried prematurely. In not giving Hannah a proper burial, it was argued, there were no funeral expenses and White could pocket the difference.

Whether inspired by a spirit of scientific curiosity or for mercenary reasons, White’s actions meant that Hannah was now set for an afterlife that she certainly doesn’t seem to have envisioned. The wealthy heiress, daughter of John and Patience Beswick of Cheetwood Old Hall, was kept for a short time at Beswick Hall, which belonged to a member of her family. She wasn’t there for long though, for soon she returned to the care of Charles White, who kept her on display in his home in an old clock case.

When White died, Hannah was bequeathed to another doctor, Dr Ollier, who in turn bequeathed her to the fledgling Museum of the Manchester Society of Natural History in 1828. There, variously known as “The Manchester Mummy”, “The Mummy of Birchin Bower” (her home in Oldham), or “the lady in the clock”, even though she was no longer displayed in one, Hannah drew the attention of interested visitors.

At the time, alongside an eclectic collection of other human remains from around the world, the idea of a wealthy local having been reduced to the status of a curiosity probably didn’t seem all that incongruous. However, when the exhibits became part of the Manchester Museum in 1867 and moved to the more salubrious surroundings of the university on Oxford Road, the focus was now on the academic and scientific study of artefacts. The fact she hadn’t received a decent burial was seen as dishonourable for a woman who had lived a Christian life and had simply wanted to avoid being buried alive.

It took the Bishop of Manchester and the Home Secretary to resolve the problem of a lack of death certificate. Stating that Hannah was now “irrevocably and unmistakably dead”, her body was finally interred in an unmarked grave in Harpurhey Cemetery. Her post-death existence had been a curious mixture of science, superstition and chicanery that seemed to sum up the spirit of the times. Even laid to rest, rumours of the existence of wealth she’d buried for safety during the 1745 continued, as did stories of her ghost haunting Birchin Bower. It would hardly be surprising if Hannah Beswick’s grave proved to be an unquiet one!

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.