Although both sides entered the First World War intending to use cavalry extensively in the conflict, and the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German cavalry units were by far the best-equipped, trained and maintained, historians broadly view the onset of the First World War as marking the end of cavalry in warfare. The stalemate of trench warfare, changes in technology, and the use of tanks, can all be cited as causes bringing the military relevance and use of cavalry to an end.

Cavalry was certainly deployed successfully during this war, despite technological advances, albeit mainly on eastern rather than western fronts. The charge of the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba lives on as one of the most spectacularly successful cavalry charges ever.

As the First World War drew to its close, Canadian cavalry made a critical contribution, possibly the most significant contribution to bringing the war to an end, at Moreuil Wood. Even in 1918, cavalry could play a decisive part in the outcome of war. Indeed, in the early stages of the war, there were some classic cavalry engagements between German Uhlans and British Lancers.

Nor was Moreuil Wood cavalry’s last hurrah; cavalry units also existed in the Second World War, and horses, mules and donkeys retained important roles. The German Wehrmacht had over half a million horses at the beginning of the war, used them in offensives and continued to acquire equids throughout the conflict. Equids are still in active service in some war zones today.

As historians Lucy Betteridge-Dyson and Jane Flynn have pointed out in their respective research and publications, what changed substantially in Britain from the nineteenth century to the early days of the twentieth century were perceptions of cavalrymen and their mounts. For centuries, the action of the cavalry in warfare had been synonymous with glory and even glamour (often to the understandable annoyance of the infantry). The horse was viewed as vital yet remained the underappreciated partner in many ways. As communication through various media increased during the nineteenth century, both the public and the soldiers themselves began to see horses in new ways.

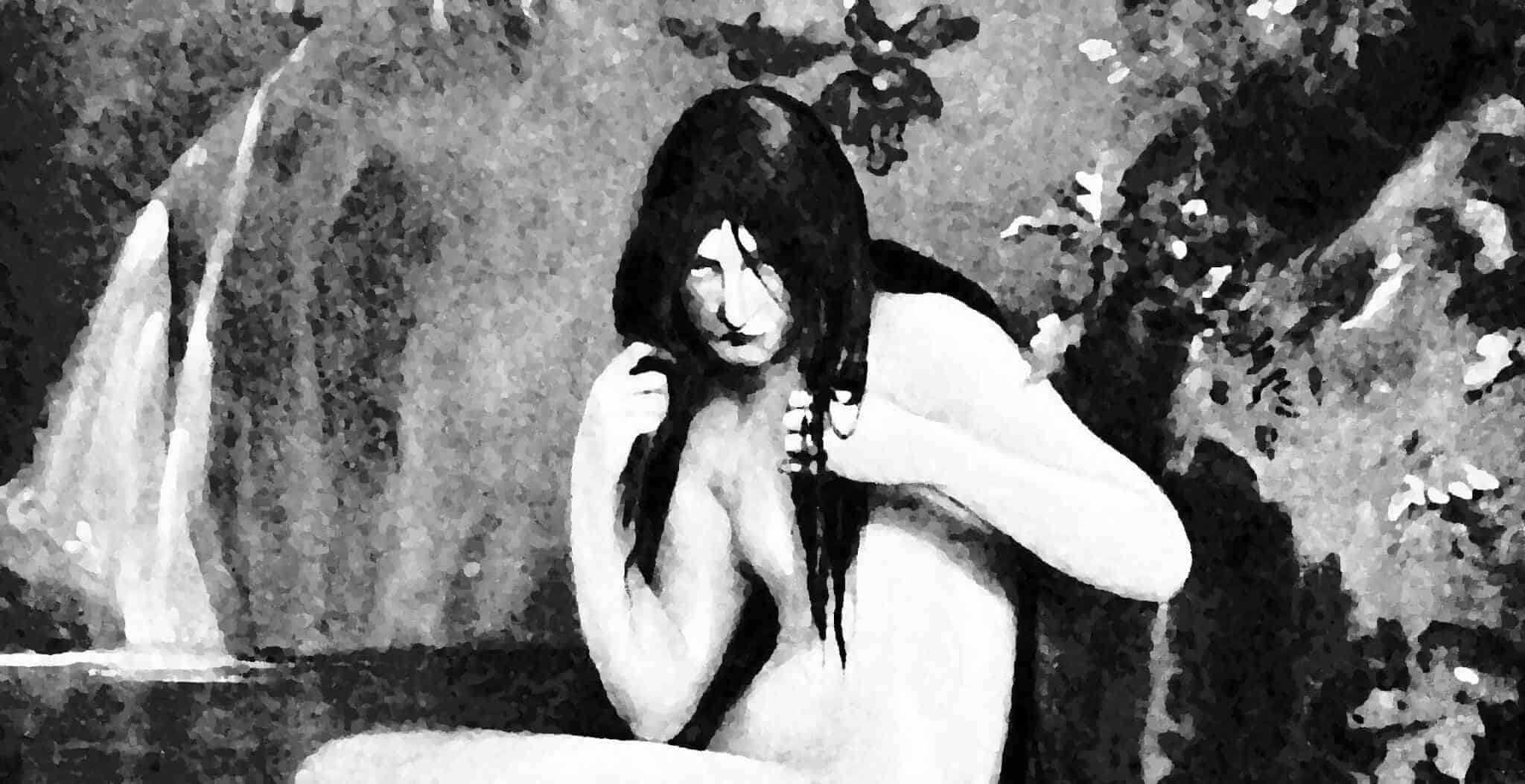

These were generally much more sympathetic ways, with the rise of animal welfare and rights organisations having an influence on public perception. With regard to horses in warfare, one organisation based in London emerged as a leader in welfare. In 1897, Our Dumb Friends League (dumb in the sense of voiceless) began to care for working animals in London, eventually opening a dedicated hospital and operating a horse ambulance service.

1916 poster promoting the Blue Cross Fund

1916 poster promoting the Blue Cross Fund

The League also organised a fund known as the Blue Cross Fund to raise money for the treatment of animals in France during the First World War. When the magnificent sum of £170,000 was raised, the League changed its name to Blue Cross and remains active in welfare under this name today. The Blue Cross used Fortunino Matania’s image of a soldier refusing to leave his dying horse – “Goodbye, Old Man” – to raise awareness of the conditions for horse and man on the Western Front.

These changing perceptions led to both the soldier and his horse being viewed as companions sharing the load, and as comrades in arms, rather than the horse simply being a vehicle, instrument or machine. Arguably there was already precedent for this, since historically horse-human pairings had been admired, even idealised: Alexander and Bucephalus being perhaps the most obvious. In medieval times, horses had received recognition and identity; Arondel, Bevis’s horse in the romance “Bevis of Hampton” is loyal to his master and a perfect example of chivalry in the form of a horse rather than a human. When Richard II’s horse Roan Barbary allows Henry Bolingbroke to carry him at his coronation, as described in the play by Shakespeare, Richard is hurt and angered at the betrayal of a horse he has fed from his own hand. He then realises that he is being unreasonable and asks his horse for forgiveness.

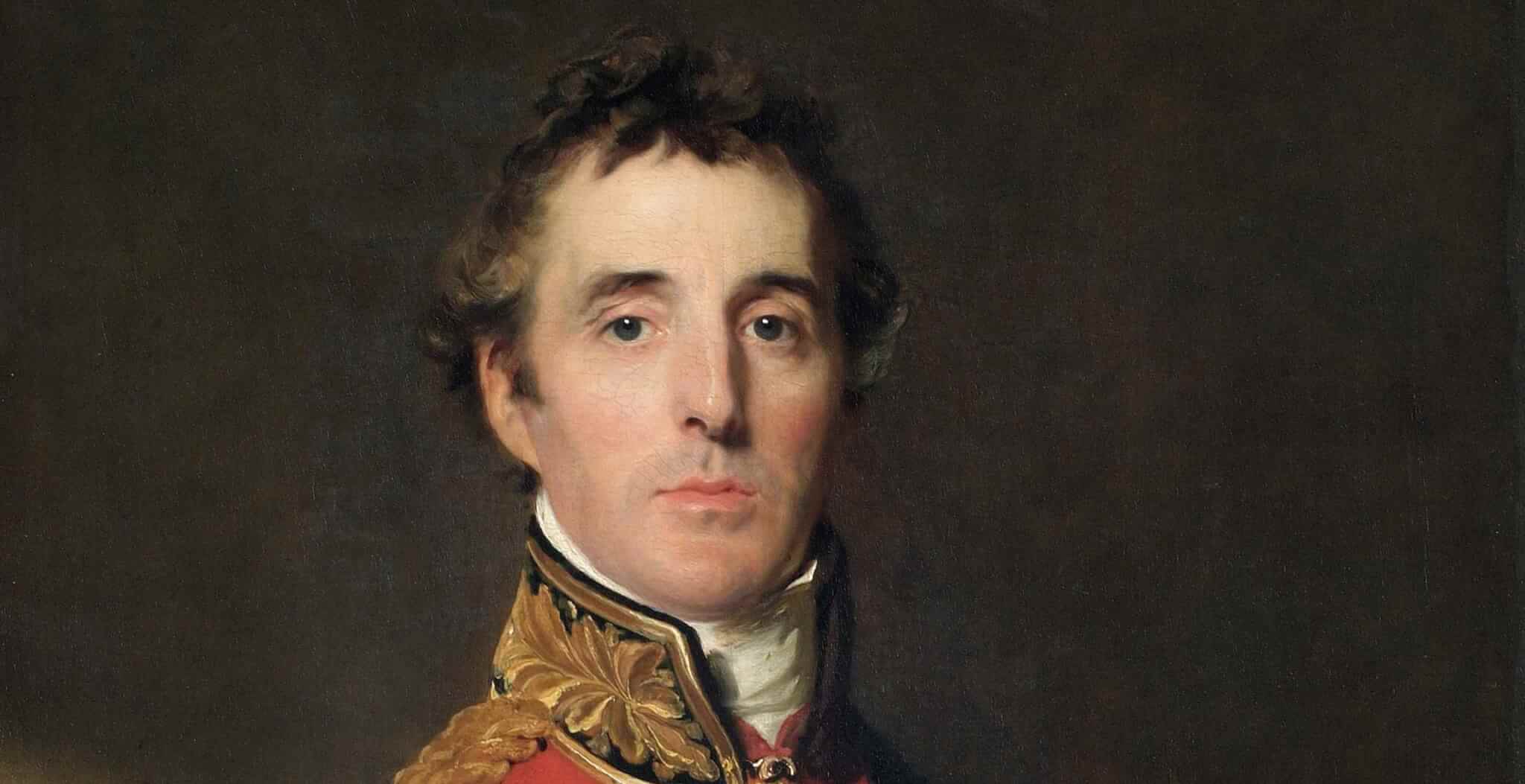

Wellington’s mount Copenhagen and Napoleon’s horse Marengo had both augmented their riders’ military success and appeal, yet Marengo in particular is a highly mythologised animal with a questionable origin story. While he has been promoted as an Arab horse acquired in Egypt, there is a strong belief in Ireland that he was an Irish-bred horse. The horse Captain Robert Byerley rode at the Battle of the Boyne would go on to claim fame in the General Stud Book as the earliest of the “Oriental” foundation stallions, the Byerley Turk, and his story too has been mythologised.

After the First World War, one British military horse would go on to achieve legendary status; this was Warrior, the mount of General Jack Seely. This intelligent and active horse survived numerous engagements, shelling, and machine gun fire to return to Seely’s home on the Isle of Wight. Warrior’s contribution as a war horse was recorded in Seely’s book “My Horse Warrior”.

Warrior was bred by Seely from an Irish Thoroughbred mare, Cinderella. One irony is that Warrior’s sire Straybit was sold to the Austrian government, which caused Seely to speculate on whether Warrior “may not, in the course of the war, have met, at fairly close quarters, his half-brothers and half-sisters, or even his father himself. We do know that the Austrians provided a great number of horses to the German army, so such an occurrence is not impossible”.

Jack Seely credited his horse Warrior with the success of the engagement at Moreuil Wood. At this time, Seely was commander of the entire Canadian cavalry, comprising 3,000 men and their horses, including cavalrymen, the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, signalmen and other support personnel. At Moreuil Wood, the mounted Canadian forces, consisting of the Royal Canadians, the Royal Canadian Dragoons, the Fort Garry Horse, and Lord Strathcona’s Horse, rode into battle in the face of German rifles, machine guns and artillery to take Moreuil Ridge.

Just as the Australian Light Horse had pulled off the seemingly impossible at Beersheba, so too did the Canadians at Moreuil Wood. The artist Alfred Munnings accompanied Seely and produced several paintings of the Canadian cavalry in action and on the move. One compelling image shows the victorious advance of Lieutenant Flowerdew’s Strathcona Horse, sabres in hand, ultimately to the loss of two thirds of the troops and their mounts. Seely stated that it was Warrior who took the initiative to lead the whole assault, not himself. He was known among the Canadians as “the horse the Germans can’t kill”.

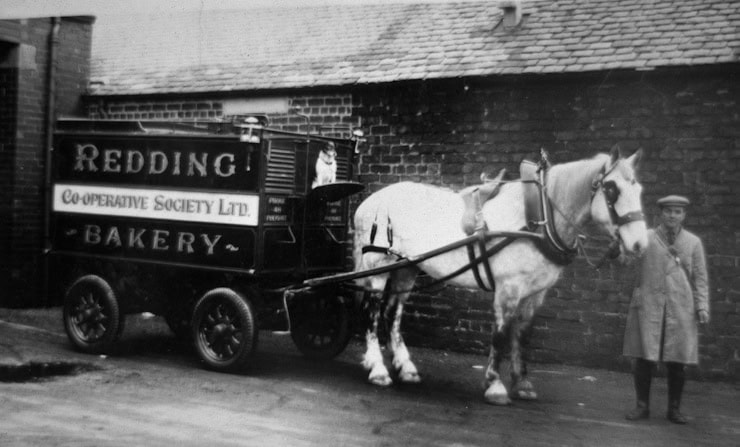

Part of the reason that there was so much sympathy for horses in the First World War is that many of the horses had been taken from towns, villages, and cities, as represented in Michael Morpurgo’s Warhorse. They were not cavalry remounts or artillery teams especially bred for the job on studs, but the horses that people knew and met every day. They were horses that were drawing cabs and milk floats, plough horses and the pony belonging to the old man who collected rags and bones.

The British Army had begun the war with 25,000 horses. By the time the war was over, more than a million horses and mules had been acquired by Britain, the majority of which did not return. Many more equids than this were used when all armies and fronts are considered, and at least eight million died in the conflict.

Not every horse was a potential recruit; their role in commerce and industry meant that canal horses, for instance, carried on working at home. As the war progressed and Britain had thoroughly scoured its own resources, it turned to Canada, Australia, and the USA for further supply. Britain also drew extensively on other imperial troops such as Indian cavalry, which played a key role at Cambrai. Horses were also shipped from Uruguay.

It is worth considering the incredible logistics needed for this supply, and the logistics that maintained the health of horses and mules at the front, including tens of thousands of tons of hay every month. Many animals died while being transported to the battlefront from various sources. One benefit that came from the war was an improved veterinary service, the numbers of army vets involved increasing from well under a thousand to over 27,000.

People felt the loss of the working horses deeply and personally, which suggests that Jack Seely’s comment that “Human beings will not realise that the affections of horses are much more closely akin to their own than is the case with any other creature,” is not entirely true. Seely said he acquired his own more sympathetic approach to horses from discussions with desert Bedouin while he was a serving soldier, but it is clear that among ordinary people in Britain the sentiments were already there.

In this war horses would face not only gun and artillery fire, but gas attacks as well as bombardment and machine gun fire from the air. The airmen of Baron von Richthofen’s famous squadrons targeted cavalry on the move. This was just one of the perils of war that Seely’s horse Warrior survived on more than one occasion. Horses as well as soldiers were issued with gas masks.

Long after the First World War, experienced cavalrymen were still arguing that horses were essential to warfare, and that if anything, the conditions of the First World War itself had been proof of that. Jack Seely for instance, wrote that it was “…in both succeeding winters on the Western Front that we learned that the horse is the only certain means of transport. The horse is vital to man in modern war. All mechanical contrivances fail when the mud gets deep; the horse suffers, but some survive to pull up the batteries, to bring up food and ammunition, to drag back the long melancholy lines of ambulances”.

The truth is that many of the military men engaged in the First World War were cavalrymen through and through, and reluctant to relinquish the role and the identity. Sir John French, Sir Douglas Haig, Captain Jack Seely and the Rt. Hon. Winston Spencer Churchill were horsemen who had been active cavalry officers in several wars. They hunted, they steeple-chased, took part in point-to-point races, and played polo. Horses were what they knew and understood. They were the last in a long line. When Churchill died in 1965 he was the last former British Prime Minister to have seen action in a cavalry charge. It was not only the end of cavalry, but the end of a particular type of politics, leading to a new, some would say professional, political class.

Even military historians such as Sir Basil Liddel-Hart, who wrote excoriatingly about the “delusion” of Haig and French on the “paramount value” of cavalry, had to admit that cavalry could be successfully engaged in the First World War. One remarkable episode in the Jordan Valley involved an amazing subterfuge in which the cavalry was secretly moved and the camp filled with 15,000 dummy horses made from canvas. Dust clouds were created to rise above the camp and give the impression of lots of activity.

“Because a preliminary condition of trench warfare existed the infantry and heavy artillery were necessary to break the lock. But once the normal conditions of warfare were thus restored, the victory was achieved by the mobile elements – cavalry, aircraft, armoured cars and Arabs – which formed but a fraction of Allenby’s total force,” wrote Liddel-Hart, concluding “It was achieved, not by physical force, but by the demoralizing application of mobility.” Whenever able to resume their traditional role of mobility, shock, and “exploiting the gap”, the cavalry proved successful.

After the First World War, while some working horses returned to Britain, thousands of horses were sold, usually in the regions in which they had served. This led to further public outcry and the setting up of a new charity to support former warhorses in Egypt, Dorothy Brooke’s Old Warhorse Fund, which remains active in welfare today as the Brooke animal charity. Many of the soldiers themselves were heartbroken at the loss of their horses, particularly the Anzac troops, whose horses were shot. “Again and again,” wrote Seely of his own experience on the Western Front “I have seen a man risk his life, and, indeed, lose it, for the sake of his horse.”

The main British focus of horses in war was on the Western Front, although Yeomanry (mounted infantry) from the Britain served in the Middle East as well as the Anzac forces of the Desert Mounted Corps. It is also worth also remembering the massive dependence on horses during this war in eastern Europe, with Russia able to commandeer over two and a half million horses from its own population. Horses here were indispensable as conditions were very different from the trench warfare in the west.

The decades following the First World War saw a long process of gradual, and often reluctant, acceptance that horses were being replaced by machines in war. The cavalry was not disappearing; it was essentially becoming mechanised, and cavalry units now frequently combined traditional mounted cavalry with tanks and armoured cars.

However, the German Wehrmacht maintained horses for use in the Second World War, many of which were used in campaigns against Poland and France. The Soviet Union also had tens of thousands of cavalry troops. The sheer visual and shock impact of armed men on horseback could still be as effective as it had been in the days of the medieval knights – or Alexander’s cavalry. Plus, of course, horses and other equids remained vitally important for transporting goods, weapons, artillery and other items, particularly in mountainous or boggy areas. As with other nations, the German cavalry units were now mixed units including mounted soldiers, armoured vehicles, motorcycles, and cars. A little-known use of horses took place in Scotland during the Second World War, which was the location of the Norwegian Army in exile. Norwegian soldiers were trained to use horses for proposed engagements in mountainous regions, but they were not deployed.

The British Army was by this time fully mechanised, and yet the days of the cavalry charge were not quite over. The last tragic and heroic figure to lead a British cavalry charge was Captain Arthur Sandeman in Burma in March 1942. Captain Sandeman was on secondment to the Burma Frontier Force from the Central India Horse, the latter being a regular imperial cavalry unit that had been through various manifestations since its foundation in 1857. The Burma Frontier Force was a paramilitary unit formed from units of the Burma Military Police.

Sandeman was out with his troop of mounted infantry near Toungou when they rode into an ambush of Japanese machine gunners, mistaking them for Chinese forces who were building defences around the city. Despite the shock, Sandeman recovered his wits quickly and drew his force together. He commanded the bugle call to attack, drew out his sabre, and set out to charge directly at the guns, shouting out a war cry.

It was a true, classic cavalry charge and Sandeman must have known it had no hope of success. Sandeman and most of his troop were killed. It was as though for one last brief moment in history, Captain Arthur Sandeman was urged on by the spirit of previous generations of cavalrymen, and as in the case of the famous Light Brigade, chose “to do and die”.

The spirit of the cavalry lived on after the war too. For several decades afterwards, some of the top performing equestrian sports teams consisted of, or included, cavalry officers. These were often some of the most charismatic and memorable riders of their time, particularly when show jumping became a massive hit on television from the 1950s onwards.

The driving force behind the post-war popularity of British show jumping was Col. Mike Ansell, whose own father had died while leading a cavalry charge of the 5th Dragoon Guards in September 1914. Following in his father’s footsteps, Ansell was a commissioned officer of the amalgamated 5th/6th Dragoons, taking up show jumping and polo in the 1930s. In 1940 he commanded the 1st Lothians and Border Horse, a yeomanry regiment. A leading show jumper of the post-war era, Col. Harry Llewellyn, had served with the Warwickshire Yeomanry, part of the Cavalry Brigade, in the Second World War.

Harry Llewellyn and Foxhunter at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki.

Harry Llewellyn and Foxhunter at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki.

Star performers wowing the crowds in Britain thanks to Ansell’s hard work in promoting show jumping included brothers Piero and Raimondo D’Inzeo from Italy with their stunning grey horses, The Rock and Rockette. Piero was an officer in the Italian cavalry, and Raimondo was an officer in the Carabinieri Cavalry Regiment. Show jumping emerged as a truly international sport in which cavalrymen were still rivals, but this time sporting rivals rather than military foes. Mexican cavalry officers were highly successful Olympic competitors in the London Olympics of 1948, winning individual and team gold medals. Irish, French, American and Soviet army officers have also been extremely successful in both show jumping and eventing.

Like many other countries, there are still cavalry units in Britain, namely the Household Cavalry, although their mounted function is exclusively ceremonial. The King’s Troop Royal Horse Artillery also maintains the skills of earlier generations through ceremonial displays. However, the British Army does still occasionally use horses for specific operational and training activities, and more than a few claim that there are still military tasks such as reconnoitring certain landscapes best done from a horse’s back!

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 29th January 2024