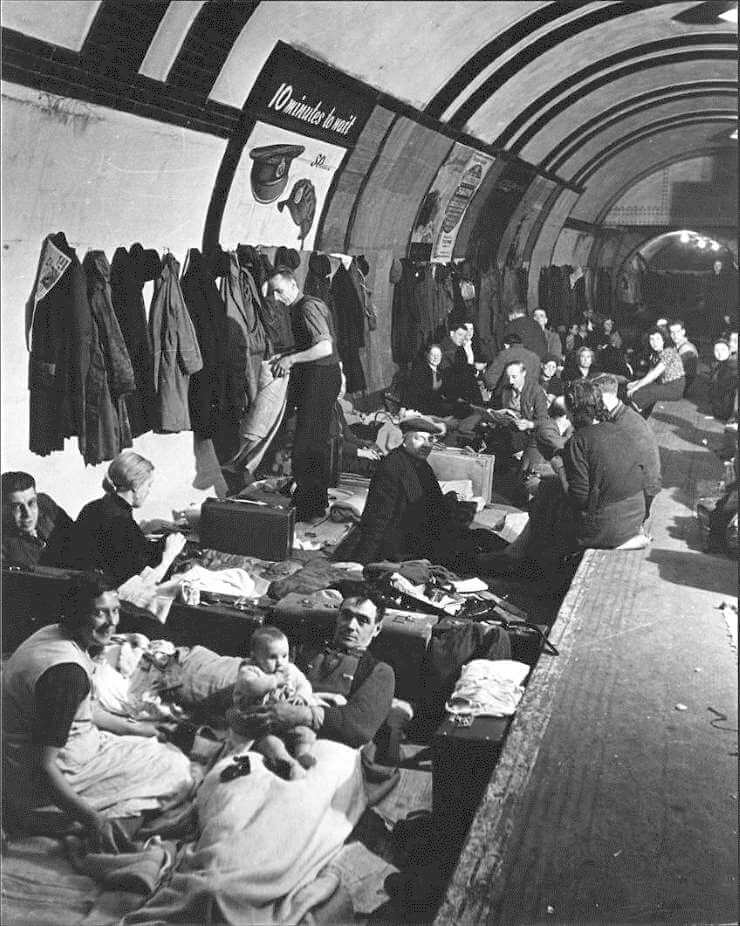

The Blitz. I’m sure as you read those words, images spring to mind. Perhaps they are images of damaged buildings, piles of rubble, hundreds of people crammed into a tube station shelter with their battered suitcases and teddy bears. And perhaps images of patriotism too. Peoples ‘keep calm and carry on’ spirit, the ‘London can take it’ vibe, the shop windows that read ‘bombed but not defeated’. This type of patriotism and morale has been coined ‘the Blitz spirit’ and has become a popular phrase in film and articles. Some even use it as a general, every day term.

What may surprise many people is that this idea of the ‘Blitz spirit’ is in fact fake, a misconstrued concept where the people’s grim willingness to carry on because they had no other choice was interpreted, perhaps purposefully, into a well-constructed propaganda tool, not just for our enemies but for the future generations of the Allies.

While writing my university dissertation, I began unpicking Britain’s finest hour to explore if this common belief of high morale despite everything actually holds true. I had read official morale reports before, and had to wonder how the government could say that people were generally ‘cheerful’, ‘highly confident’ and ‘taking the bombing with good heart’ while their homes, schools and lives were being systematically destroyed. At the height of the seventy-six nights of consecutive bombing London was suffering, their spirit was apparently ‘extremely good’.

I began to question how accurate this could be. To compare how the people really felt about the bombing against the government view, I began to read personal letters and diaries of those who lived through it. I looked to different elements of society to get as clear and wide a picture as possible; shop workers, ARP wardens and government officials, those who lived the high life and those who lost it all. I found a general consensus; no high morale to be found. As expected, people spoke of the psychological effect; the fear of being trapped under the rubble of their own house, of not getting to the shelter in time. Others spoke of the sheer inconvenience; the huge craters in the road preventing the buses travelling on their usual route, making it impossible for many to reach work.

To put it another way, I read no-one with the feeling that yes, they were in fear for their lives from the moment it began to get dark until the sun came up again, for seventy-six days on the trot, but never mind, let’s put the kettle on. In fact, there wasn’t really a single day I could match the official government opinion to people’s personal feelings. So now I had to answer the question; why?

The idea I immediately stumbled across was ‘the myth of the Blitz spirit’, a concept created and indeed confirmed by the historian Angus Calder. He theorised that in fact what seemed to be high morale, i.e. people with lots of fighting spirit, mostly unfazed by the damage to their homes and lives and with that British ‘keep calm and carry on’ concept, was in fact a ‘grim willingness to carry on’, or passive morale. This means that they had this supposed fighting spirit because they had to, because they had no other choice, rather than because they wanted to carry on!

This was obvious at the time to those individuals documenting it, expressing their true feelings in their diaries and letters. But the government did not read these, nor even consider them, when it came to measuring the morale of the country. Therefore what they saw were women continuing to hang out their washing in their bomb-churned gardens, men continuing their journeys to work, simply taking a different route instead, and children still heading out to play in the streets, using bomb sites as their new playgrounds. What Calder argues is that these observations were incorrectly interpreted as high morale, simply because from the outside it seemed as though everyone was basically happy to continue as normal.

It was not considered that they were trying to live as they had before because there was no other alternative for them. No one thought to take a look inside, to actually ask the average person on the street how they were, if they were coping, or perhaps what they needed to help them out a little. Even publications of the time spoke of how well everyone was coping, making the destruction of these nightly raids appear a minor inconvenience.

Obviously it was in everyone’s best interest to read that even those worst affected were managing just as well as before. This would encourage an overall positive morale across the country, and perhaps as I mentioned before, even convince our enemies that they could not break us. Perhaps this was then in itself a self-fulfilling prophecy; a case of ‘Mrs and Mrs Jones down the road seem to be rather cheery, so I can’t exactly complain’. Even if this were the case, the grim willingness remained.

So maybe they wanted this morale to be misinterpreted. Maybe someone along the line did mention that surely no one could be that chipper after losing their home, and another higher-ranking government official told them to be quiet, this could actually play to their advantage. Or perhaps they simply did believe that an outside look only was sufficient. Either way, what we coin to be that well-known Blitz spirit was in fact not an accurate representation, and perhaps people were not really as happy to ‘keep calm and carry on’ as we would like to believe.

By Shannon Bent, BA Hons. I am a recent War Studies graduate of the University of Wolverhampton. My particular interests lie in twentieth century conflicts, specifically the social history of the First and Second World War. I have a passion for learning outside of the education system and am seeking to use this passion in museum curation and exhibit creation to create interactive spaces for people of all ages and interests to enjoy, while promoting the importance of history to the future. I believe in the importance of history in all its forms, but especially military history and war studies and its paramount role in the creation of the future, and its use to guide us and to learn from our mistakes.