Street brawls between fascists on one side and ‘Antifa’, communists and anarchists on the other. Although this may sound like something from the news of Portland, USA in 2020, this is East London in 1936.

The 1930s was a period of seismic political change throughout Europe. Fascist dictators took power in Germany, Italy and Romania and left wing and communist movements rebelled against expanding fascism in countries like Spain. In Britain, this tension culminated in a violent event in the East London area of Stepney, on Cable Street.

The murderous pogroms in Russia and elsewhere in Europe had lead to many Jewish refugees arriving in the East End of London from the early 1900s. Stepney at the time was one of the poorest and most densely populated suburbs of London and many new immigrants settled in the area. By the 1930s the East End had a distinct Jewish population and culture.

Sir Oswald Mosley was the leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Mosley met Mussolini in early 1932 and very much admired and modelled himself on the dictator. Mosley even created a new, sinister organisation – The Blackshirts – a quasi-military group of around 15,000 thugs, modelled on Mussolini’s Squadrismo.

The Blackshirts were known for their violence, after attacking a left-wing Daily Worker meeting in Olympia in June 1934. Much like elsewhere in Europe, there was growing antisemitism in Britain in the 1930s, partly as a scapegoat for the ongoing effects from the Great Depression.

But as the number of fascists was growing, so too was the opposition against them. Trade unionists, communists as well as the Jewish community were becoming increasingly mobilised. When Mosley announced a march into the heart of the Jewish community in the East End of London, planned for Sunday 4th October 1936, the community was in disbelief and it was a clear provocation. The Jewish People’s Council presented a petition of 100,000 names to urge the Home Secretary to ban the march. But, the BUF had the support of the press and police, and with the Daily Mail running headlines in the 1930s such as “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” the government failed to ban the march and the people of the East End set about organising to defend themselves.

In the lead up to the march the Blackshirts held meetings on the edge of the East End and distributed leaflets designed to whip up antisemitism in the area. The Daily Worker called people to the streets on the day of the march, to block Mosley’s way. There were many who were worried about violence and the Jewish Chronicle warned its readers to stay home on the day. Many other groups such as the communists and Irish Dockers encouraged the defence of the diverse community from fascist intimidation. The Communist Party even cancelled a planned demonstration in Trafalgar Square and redirected its supporters to the East End.

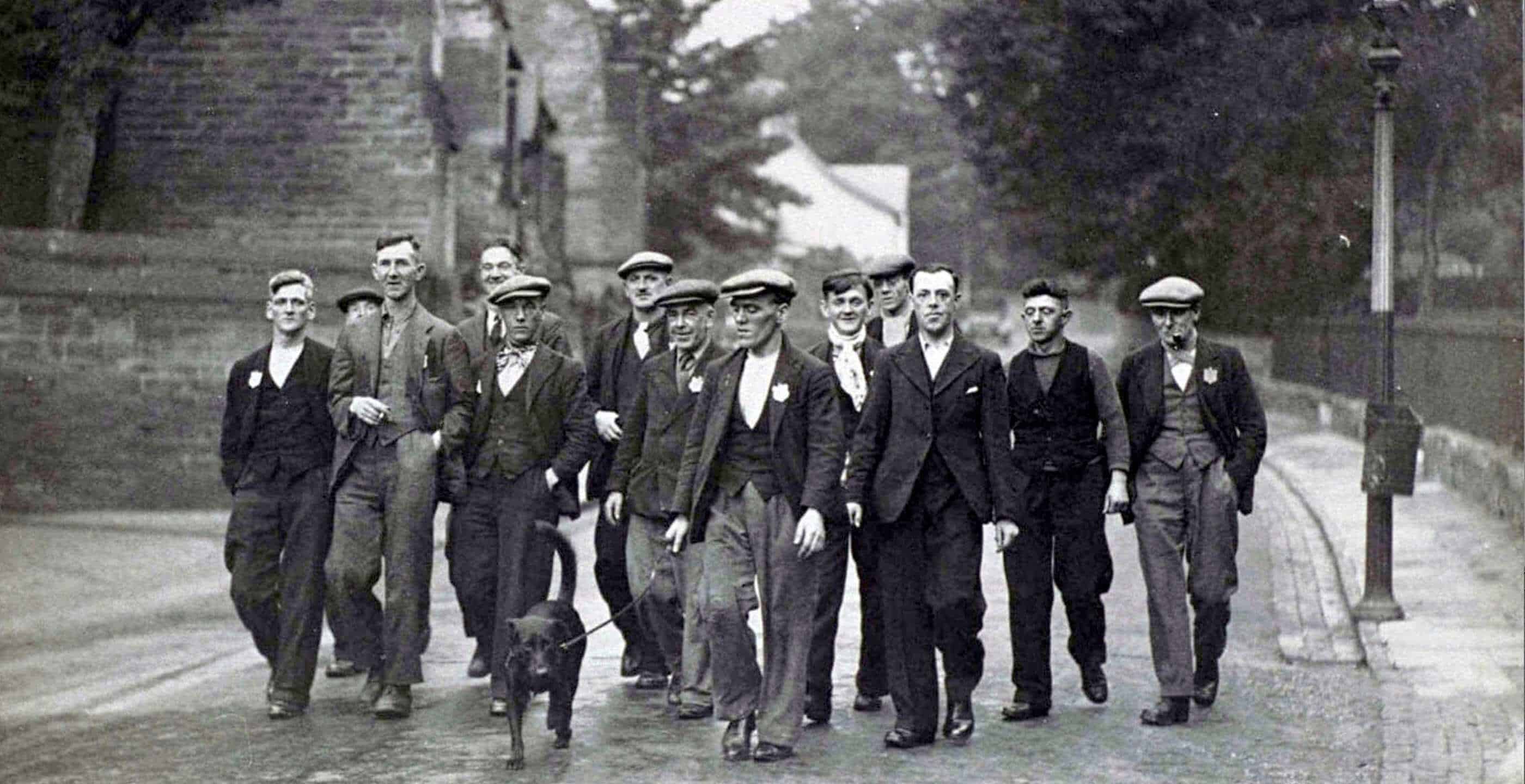

On Sunday 4th October thousands of antifascists began to gather at Gardeners Corner in Aldgate. The battle lines were set as Mosley gathered his men at the Royal Mint by The Tower of London. The police amassed 6,000 officers to clear a path for them into Whitechapel. The police used mounted officers at Aldgate to beat back the crowds onto the pavements but thousands more were streaming into the area. Four sympathetic tram drivers strategically abandoned their vehicles to help block the road to the fascists.

“Down with the fascists!” chants were heard across East London as the police clashed with the community blocking their way. Communists, Jews, Irish Dockers, Trade Unionists all united under the chant “They Shall Not Pass!”

As the police could not get through the crowds towards Whitechapel, Mosley decided to change the route and head down narrow Cable Street, that ran parallel to his original route. The Blackshirts were headed up and flanked by the Metropolitan Police as they headed into Cable Street.

The community was ready. They had begun constructing barriers in Cable Street early that morning to block their path. To stop mounted police charges, Tom and Jerry tactics were deployed as glass and marbles were left in the street and pavement slabs pulled up. Nearby the Communist Party established a medical station in a café.

The police were met with fierce resistance. Everything from rotten fruit to boiling water rained down on them from windows on all sides. The Met reached the first barrier, but brawls broke out and the police withdrew and demanded that Mosley turn around.

Celebrations broke out across the East End that afternoon. 79 antifascists were arrested, many of whom were beaten by the police, some even sentenced to hard labour. Only 6 fascists were arrested.

Legacy.

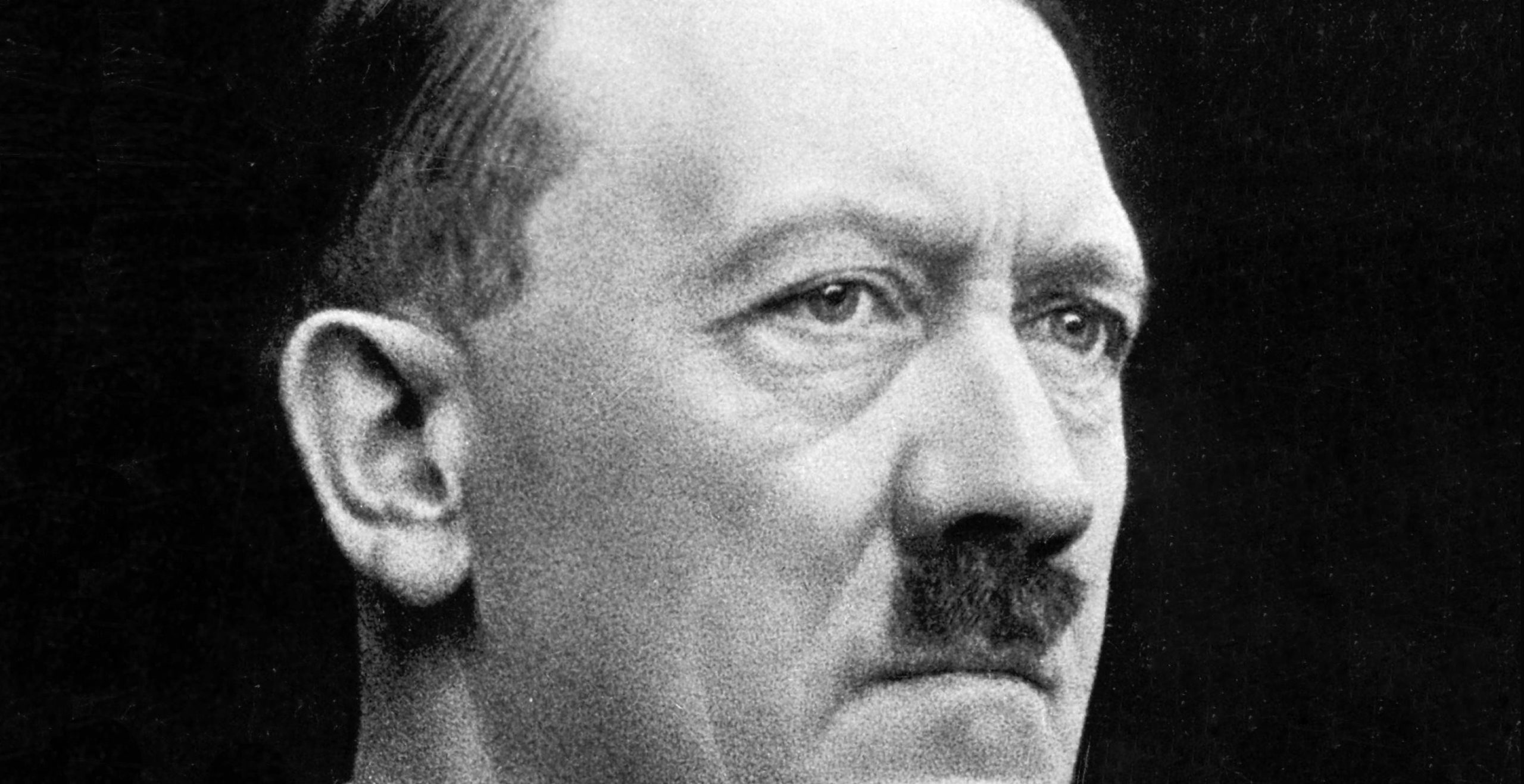

The events of the day directly led to the passing of the Public Order Act in 1937 which banned the wearing of political uniforms in public. Moreover, Mussolini, disappointed in Mosley, withdrew his substantial financial support for the BUF. Two days after the events at Cable Street, Oswald Mosley was married in Germany, in the home of Joseph Goebbels, with Hitler as a guest.

Even though this was not the last of the violence by the Blackshirts, they and the BUF became deeply unpopular in lead up to the Second World War. Mosley and other leaders of the BUF were imprisoned in 1940.

Many antifascists who took part in the Battle of Cable Street donated money or travelled to Spain to join the International Brigade to fight fascism, with up to a quarter not returning. The strong links between the movements can be seen in the adoption of the “They Shall Not Pass” slogan from the “No Pasarán!” chant used by republican fighters in the Spanish Civil War.

Mural.

Today the memory of this event is commemorated with a 330m2 mural on the side of St George Town hall. Commissioned in 1976, the colourful mural was inspired by the famous Mexican mural artist- Diego Rivera. The designers interviewed local people to inform the design and used a fisheye perspective to portray the battle, the banners and the people who defended the community. The mural reminds us of the diverse communities that have lived in the area over its recent history. Though the mural has been attacked several times it remains as a memorial to the East End’s powerful ability to unite in the face of a crisis.

By Mike Cole. Mike Cole is a coach tour guide for the UK and Ireland. He is a passionate historian, whose family hails from East London.