“In this country, it is good to kill an admiral from time to time, in order to encourage the others”.

This comment is taken from Voltaire’s ‘Candide’ which commented on the execution of the Admiral John Byng on 14th March 1757, with the charge of “failing to do his utmost”.

Byng was a naval officer fighting in the Seven Years War when an order to relieve a British garrison on the island of Minorca was not carried out.

As admiral he had made the decision to return to Gibraltar, rather than land further troops to seize the fort on the island of Minorca.

This fateful choice led to his subsequent court martial and a guilty verdict soon followed. Despite the calls for clemency, the pleas were not heard. His death came on a cold, dreary and blustery March morning, his body peppered with bullets from a firing squad.

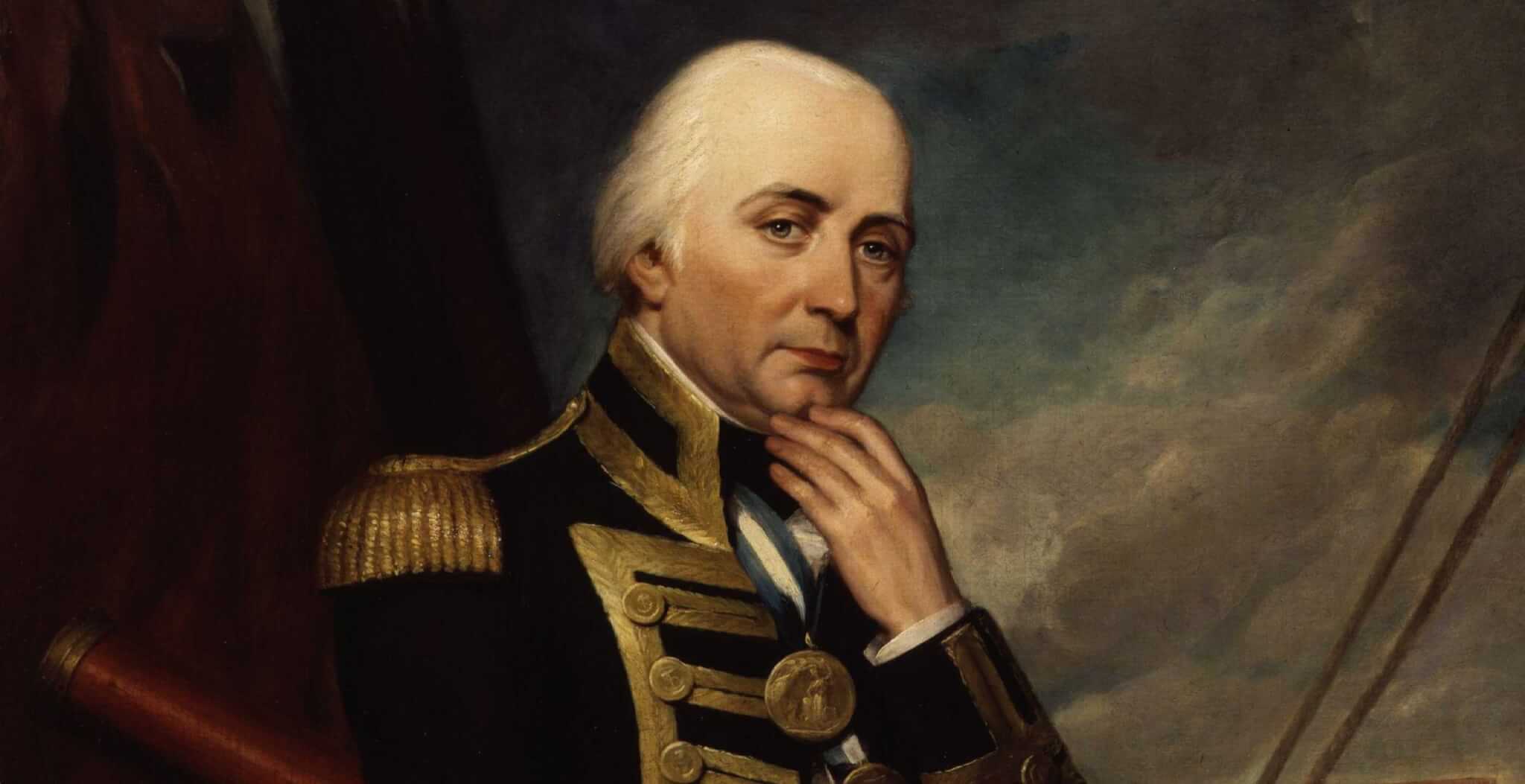

The story of Admiral John Byng begins much earlier in 1704, when he was born in Bedfordshire, the son of Rear-Admiral George Byng, 1st Viscount Torrington. His father would later serve as Admiral of the Fleet and so it was that John was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps.

His father was an important figure and had been instrumental in securing the coronation of King William III. John Byng was a man of great standing, with impressive fortunes. He was well-known as a great naval officer, serving in a series of successful battles, earning him great accolades and affection from the public as well as the monarchy.

With such an impressive record set by his father, young John had some big shoes to fill. He began his career with the Royal Navy at the age of thirteen, which happened to coincide with his father serving as admiral, a highlight of an illustrious career.

Byng was given many postings in the Mediterranean and in time began to climb through the ranks. At the age of nineteen he was promoted to lieutenant and at the age of twenty-three became a captain of the HMS Gibraltar.

As a serving Royal Navy officer, in his forty years of service he earned himself a solid reputation and received promotion in due course. However, in his service in the Mediterranean he did not see much action, unlike his father. In 1742 he was given the role of Commodore-Governor of Newfoundland and three years later was appointed as rear-admiral. Whilst serving in numerous roles he also dabbled in politics and served as a Member of Parliament for his Rochester constituency, a position he held until his death.

In the meantime, he was made Vice-Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet. Byng’s professional life grew more successful, with increasingly important roles being awarded to him, as well as his life back at home serving as a politician. He was able to purchase a large estate and commission a great mansion in 1754 known as Wrotham Park.

Meanwhile, as Byng’s career grew from strength to strength, an epic decade of violence was about to ensue with the advent of the Seven Years’ War which began in 1756. This was a global conflict, an all-encompassing battle which spread across continents and effectively split European powers into two opposing forces.

On one side was the coalition of British forces, Prussia, Portugal and the House of Hanover as well as some smaller German states whilst in the other camp, an alliance of France, the Austrian controlled Holy Roman Empire as well as Saxony, Russia, Spain and Sweden.

This was truly the first world war of its kind, encompassing great international powerhouses who fought on various continents. The British Prime Minister at the time, the Duke of Newcastle had been cautiously optimistic that important alliances would prevent an ongoing battle on the European mainland, however he was proved to be wrong.

It was at this point that the French began to convene at Toulon, forming an impressive and formidable force. They decided to open their campaign against their British rivals by attacking the island of Minorca which had been a British possession since its capture during the War of the Spanish Succession in 1708.

As the threat of war loomed, the French naval officers took their position and invaded the fort in 1756. Meanwhile, Byng was serving in the Channel when he received orders to sail to the Mediterranean to provide relief of the British garrison at Minorca.

Byng, who had been promoted to admiral, immediately realised that the navy did not have the time to prepare a proper plan of attack nor did they have enough money in which to execute this plan. Many of the ships were not in a particularly adequate condition for sailing into battle and the fleet were in desperate need of extra manpower.

Immediately, Byng and his men encountered issues when his fleet was delayed at Portsmouth as hastily extra crew were found. On 6th April 1756 the ships set sail for Gibraltar and arrived the following month.

As preparations for looming battle commenced, it soon became clear that Byng did not have confidence in the order he received. Fearing that the garrison of Fort St Philip could not hold out against the mighty manpower of the French and knowing that the British navy was understaffed, he seemingly left from Portsmouth fearing the worst.

His worries were conveyed in a letter which he sent to the Admiralty from his base in Gibraltar. However the governor refused any advance on increasing the number of soldiers. Byng and his men would subsequently proceed, despite the admiral himself lacking in confidence in the mission.

Meanwhile, the French looked to be suitably prepared as they landed around 15,000 troops on the island whilst Byng and his men sailed close to the east coast. It soon became clear that the French troops had taken over the island before any British soldiers could be deployed.

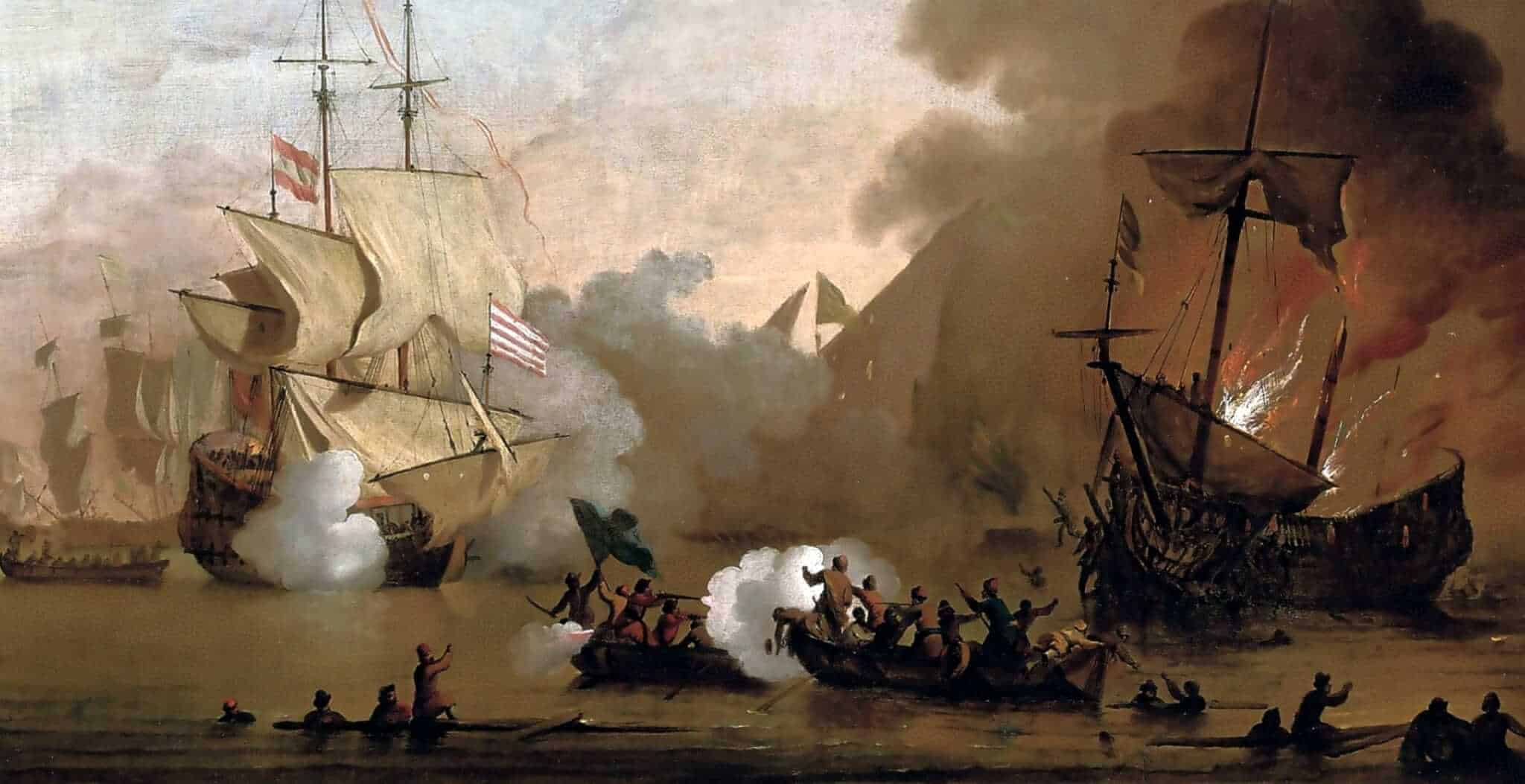

The fight which ensued was known as the Battle of Minorca and took place on 20th May 1756 which would set the stage as the first sea battle of a long and arduous Seven Years’ War.

Byng gathered together his twelve largest ships, facing the French line and attacked the fleet from an angle, with his leading ships ploughing into battle whilst the others were out of the firing range. The French were easily able to damage the leading ships whilst incurring little damage to theirs.

Meanwhile, the rear of the line which included Byng’s flagship were not even within range of firing canons. The British ships in front were faced with serious damage, whilst the French remained relatively unscathed by this overly cautious assault by the British.

Byng and the Council of War had made the decision that the fleet could not withstand further bombardment by French ships, nor did they pose an adequate enough chance in relieving the captured garrison.

His choice to not detach any further troops was agreed by himself and the War Council, who felt at the time that it would be a needless waste of necessary manpower and believing that it would also have no effect on the French.

Byng subsequently gave his orders to return to Gibraltar, a decision which ultimately sealed his fate.

This was met with cries of outrage back in London. A combination of fury, uproar and disgust came when a letter arrived in London detailing his decision. The King at the time, George II was up in arms upon hearing the news, stating in disbelief, “This man will not fight!”

When Byng and his men’s arrived back at Gibraltar, the fleet finally received the necessary reinforcements with an extra four ships as well as a 50-gun frigate. Moreover, repairs to the ships already damaged were carried out and extra provisions loaded. However Byng was not destined to set sail to Minorca once more, instead he received instructions ordering his return to England.

Back on home soil he was immediately placed in custody and in late June, the news of Fort St Philip’s surrender to the French only worsened his case.

The fort was now officially in the hands of the French and Byng’s responsibility for the matter placed him in an increasingly precarious position.

In England, the incident garnered widespread attention with crowds chanting:

“swing, swing Admiral Byng”

Meanwhile, the court martial made headline news in many of the newspapers and in December he was charged with “failing to do his utmost”. Byng defended himself but to no avail. Whilst the court recommended mercy, calls for clemency looked to be falling on deaf ears.

The government ignored these pleas and George II chose not to spare Byng.

On 14th March 1757, in a blustery Portsmouth harbour, the monarch played host to this macabre spectacle. Byng was blindfolded and escorted onto the deck, kneeling down on a cushion and holding a white handkerchief in his hand, he finally met his fate.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 5th April 2022.