The purpose of D-Day, the Normandy Landings on 6th June 1944, was to establish a breach in the formidable Nazi military line that now defined the vast area of Europe controlled by Hitler’s forces.

The Allied logistics for Operation Overlord, the planned invasion of Europe, were on a massive scale. So too was the shadow operation that attempted to distract the Nazi leaders from Operation Overlord and the real plans for D-Day by convincing them that it would take place not in Normandy, but elsewhere. The amassing of troops and equipment was concealed by various ruses. Trickery, misinformation, and even phantom army units were all part of the deception. For the misinformation to succeed, espionage, counterespionage, double-crossing, and double bluffing were the orders of the day.

The biggest double bluff of all was the fact that both sides knew there was to be an Allied assault on the heavily fortified coast of Nazi-dominated Europe, known as Rommel’s Atlantic Wall. It was simply a question of when and where. In principle the Wall, as far as the Nazis were concerned, stretched from Scandinavia to Spain.

Great efforts were made to protect it, including the use of obstacles such as hedgehogs (spiked metal constructions) and other barriers on the beaches, as well as minefields on land, and the creation of no-go zones by flooding to create coastal marshland that was difficult to cross. Further mines in the sea awaited unwary shipping, and manned torpedoes and U-boats were patrolling the waters off the Atlantic Wall. Nazi gun batteries on land guarded the air. It was a forbidding psychological barrier as well as a military one.

A broad strategy of deception known as Operation Bodyguard was discussed and approved by the Allies by December 1943. The aim was to convince the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht that the proposed Allied invasion would take place elsewhere from the chosen location and on a different date. The most obvious place for the invasion – Pas-de-Calais, directly opposite the south coast of England – was promoted by spies in the employment of British Military Intelligence. It appears, perhaps surprisingly, that this was widely accepted by the Abwehr, the Nazi Intelligence service, when it was suggested to them by captured Allied spies, or those active in the double-cross and superficially serving the Nazis.

However, that was not the only option promoted by Operation Bodyguard. Northern Norway, southern France, and the Balkans were all put forward as suggestions. As well as distracting by suggesting alternative places for invasion, decoys in the form of dummy equipment – tanks, military vehicles, and aircraft – were assembled to suggest large forces gathering, particularly for the Pas-de-Calais option. Wooden aeroplanes occupied mock airfields, complete with control centres, fake ships sat in fake ports, and counterfeit military camps suggested large gatherings of troops.

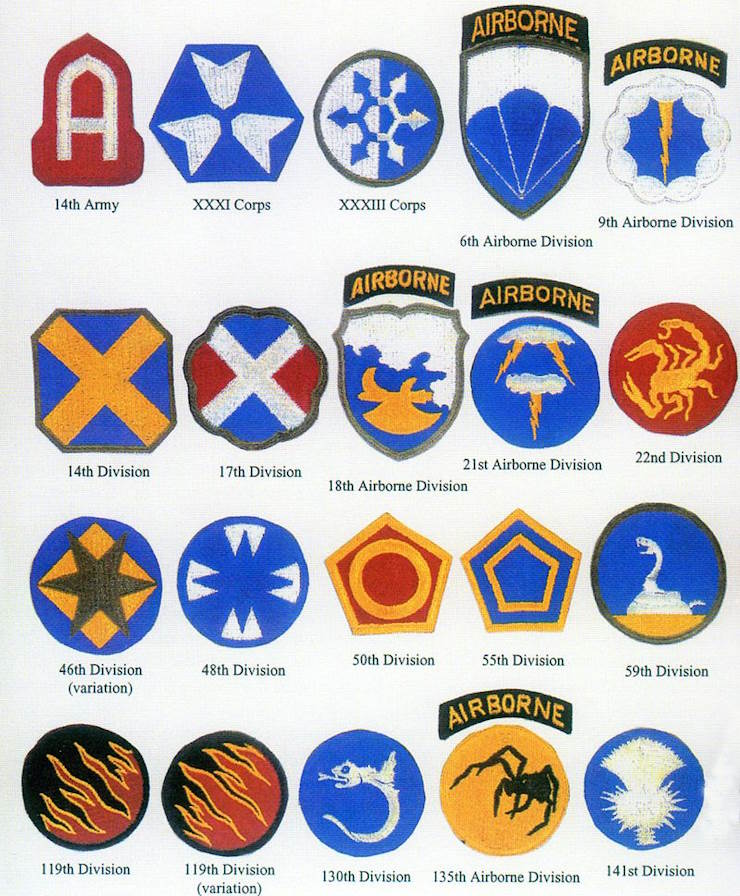

There were even phantom, or ghost, army units. The best known was probably the First United States Army Group (FUSAG), supposedly led by General George Patton. Giving the names of high-profile and charismatic military men gave credence to the deception. The units had fake insignias and equally fake troop manoeuvres, and during the build-up to D-Day, some 2000 troop train journeys were simulated in Britain. Use of signalling and lighting could also create an impression of troops by mimicking life in training camps. Camouflaging suggested sites were centres of bustling activity when in reality nothing military was happening there. Sounds of army life were belted out through speakers, creating a row that could be heard for miles.

Phoney radio traffic played a significant part as well. Artificial wireless (radio) broadcasts suggesting army exercises and logistics misled Nazi intelligence. The cracking of codes and “recruitment” of Nazi spies landed in Britain provided valuable information to the Allies. It must be said that the spies sent to Britain by the Nazis were often hapless, ill-prepared, and decidedly unlucky. Several agreed to become double agents even before they had a chance to use their radio transmitters to connect with Nazi military intelligence. Others were simply tried, found guilty of treason, and shot or hanged. Misinformation was deliberately leaked through existing diplomatic channels and double agents. One way or another, by 1944 British Intelligence effectively controlled any Nazi spy network on the island. Having the means to decrypt Axis messages, particularly those between the Wehrmacht and senior Nazi officials, was essential to success too.

The two Operation Fortitudes, North and South, were the subplans of Operation Bodyguard that put the principles of deception into practice. Operation Fortitude North was to suggest to the Nazi command that D-Day would take place in Norway, while Fortitude South indicated the landings would take place at the Pas de Calais. British agents manipulated the stock market in Stockholm to boost Norwegian stocks, suggesting an invasion of Norway was imminent.

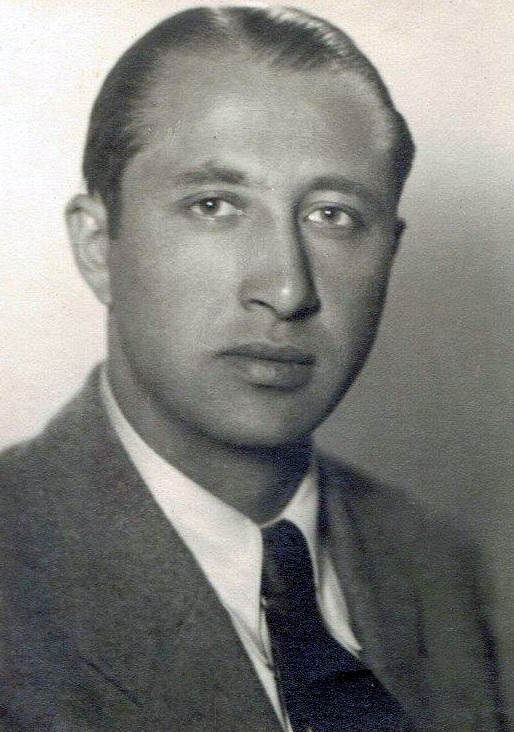

Preparation for D-Day was dependent on a network of mercurial secret agents, several of whom were in constant close contact with both Allied and Axis intelligence staff. Both Fleming brothers, Ian and Peter, were deeply involved in Military Intelligence during the war. Many clandestine meetings and introductions took place in neutral Portugal. Here it was that the idea for James Bond probably took root, perhaps inspired by the espionage work of Dušan “Duško” Popov, a key figure in Operation Fortitude, employed by British Intelligence and responsible for the feeding of much misinformation to the Abwehr, the Nazi Intelligence services.

There was at least one real magician involved in work on subterfuge behind the scenes. Jasper Maskelyne was a member of a famous dynasty of stage magicians. While he didn’t work directly on Operation Fortitude or the D-Day Landings, he was deeply engaged in some spectacular deceptions, mainly in Egypt. He designed fake military vehicles and vessels, including battleships and tanks.

Maskelyne convincingly disguised tanks as ordinary civilian vehicles such as lorries. His most impressive trick – for it had all the hallmarks of true stage magic – was the creation of a replica of Alexandria Harbour miles away from the genuine Alexandria. It worked. Axis planes attacked the bogus illuminated harbour rather than the real one. Previously, Maskelyne had come up with the great idea of pretend sheep dotting the ground where enemy gliders were going to land. They were fleeces, not actual sheep, and filled with explosives. The Cairo training and preparation certainly provided further innovative ideas, some of which may have influenced the preparations for the D-Day deceptions.

Disguising tanks as other vehicles was one aspect of deception in wartime. Creating dummy tanks was another, and this was a technique with history on both sides, dating back as far as the First World War. Inflatable tanks, using rubber tubes covered in fabric with tank markings and even turrets and mock guns, could be extremely convincing. (Of course they could also be easily deflated if shot or accidentally punctured, conjuring up interesting images for anyone who has witnessed the effect in smaller inflatables!) However convincing they were from a distance and even at close quarters, they could be easily turned over by gusts of wind and an inflatable Sherman tank could be lifted and carried by just four men!

During Operation Fortitude leading up to the D-Day Landings, these inflatable tanks suggested the allies had many more operational tanks than was the case, and their locations helped to draw attention away from where the real invasion was to take place. Making the dummies visible at locations in south-east England added credibility to the idea that the invasion would be across the Channel to Pas-de-Calais.

The deceptions continued on the great day itself.

Three naval deceptions (in fact involving the co-ordination of Allied naval and air units), Glimmer, Taxable, and Big Drum were put into operation. Taking place very early in the morning of 6 June, Taxable simulated an assault on Cap d’Antifer, about 80km from the actual Normandy Landing beaches, while Glimmer was a counterfeit invasion of Pas-de-Calais, the location that had been impressed on the Abwehr. The Royal Air Force dropped large quantities of “chaff”, clouds created from chopped aluminium foil, to give the impression of a fleet of ships on radar screens. This, it was hoped, would lure Nazi forces to the fake landing sites. This was a skill in itself, as repeated circuits had to be made to drop enough chaff to simulate the movement of a fleet.

Taxable involved the use of 18 small boats, both Harbour Defence Motor Launches (HDML) and RAF Pinnaces. More chaff descended from Lancaster Bombers of 617 Squadron, the famous Dam Busters unit. The Taxable fleet laid mines before returning to harbour. The Stirling Bombers of No. 218 Squadron supported Glimmer, and under their protection twelve Harbour Defence Motor Launches jammed the enemy radar using jamming gear and radar-reflecting balloons. Operation Big Drum was a further distraction exercise carried out by four HDMLs without air-borne support. Once again they were equipped with radar jamming gear, but unlike Glimmer and Taxable, they received no response from the opposing forces.

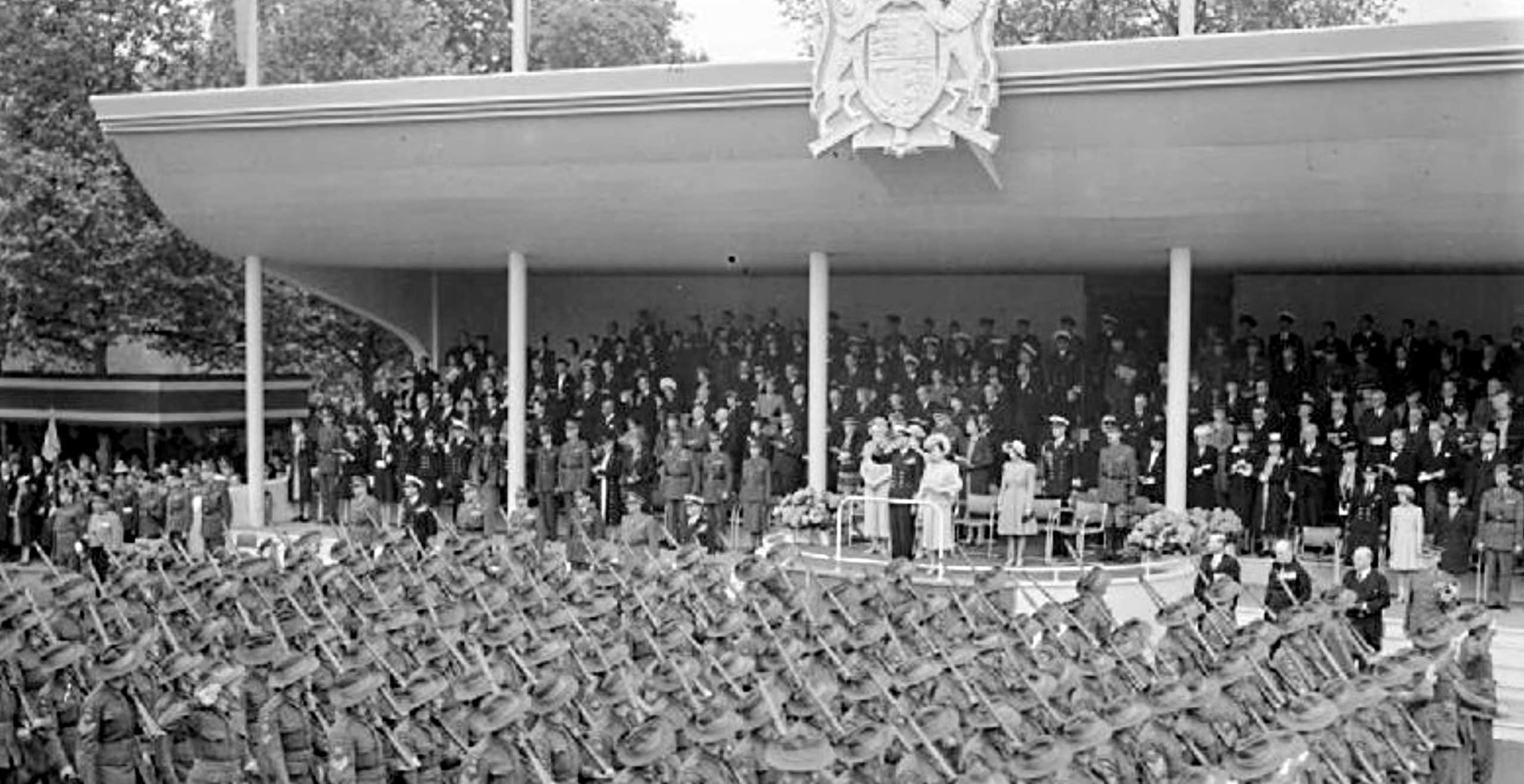

D-Day required huge resources; 20,000 workers were required just to make the concrete caissons for two artificial harbours created and taken across the Channel under Operation Mulberry, part of Operation Overlord. A total of 332 tugs were required to draw them into place. 347 British, Canadian, and American minesweepers took part in the operation to clear the channel of mines and other obstacles prior to D-Day. Pluto, the Pipe-line Under the Ocean, carried oil supplies from the British mainland to Europe to ensure that the many vehicles of the allies could continue to work. The scale of the operation during war conditions inspires awe today, as does the scale of deception required to cover up what was really happening.

Throughout the preparation and deception, two astute and highly engaged communities received incomplete information about the plans for D-Day. They were the British civilian population, and the British press. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) did recruit some trustworthy correspondents, but it was clear that when it came to security, the fewer who knew and the less that was known, the better. Only when the BBC Radio service announced at 9.30 am on 6 June that “D-Day has come” were press and public made aware that the long-awaited landings were already well advanced.

What is more, the deceptions preceding D-Day, particularly Operation Fortitude, laid the groundwork for future espionage during the Cold War. The standards now included the recruitment and cultivation of double agents, the use of decrypted information to provide valuable information on enemy plans, and a theory of deception that could be used as a model to train future intelligence operatives. Not to forget, of course, its influence on spy literature that endures to this day.

In summary, the deception operations that were an essential part of the preparations for D-Day required as much commitment as the D-Day Landings. Without the net of deception that hid the work behind the scenes for weeks, months, even years, the amphibious craft, the Rhino ferries for transporting equipment and men, the Churchill and Cromwell tanks with howitzers, the armoured vehicles, American locomotives, smoke generators, and flamethrowers would have been assembled to little purpose. This was equally true of the 130,000 British, American, and Canadian troops who were the heroes of the day and the following weeks. It was a truly breath-taking achievement, shrouded in a web of subterfuge worthy of the world’s greatest magicians.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 28th May 2024