Hounslow Heath, 10 miles west of London, is not a place traditionally perceived to be of any great importance or historical interest. It has for centuries loomed small in the scheme of things. That is until a 17th century Prospect of His Majesties’ Camp on Hounslow Heath sparked a Lockdown project that has corrected this misconception, to provide a rich contribution to British history, generally and specifically a less disapproving perception of one of its most enigmatic Kings.

On the death of his older brother, Charles II, and with no heir, James became king in 1685, only to be ousted three years later in a bloodless revolution led by his daughter and son-in-law. Traditionally cast as a cruel absolutist who oversaw a level of tyranny representing an aberration in British history, more recent attributions have been kinder to Britain’s last Catholic king. Indeed, his military, political and religious ambitions centred on Hounslow Heath expose a gifted publicist and showman ahead of his time, propagating and pursuing the Catholic cause by means of the greatest displays of military force ever assembled on British soil in peacetime.

Hounslow Heath’s geo-political value is first recorded following the barons’ meeting with King John at Runnymede in 1215 forcing him to accept and seal the Great Charter of Liberties. However, the barons subsequent victory tournament had to be relocated from Stamford in Lincolnshire to Hounslow Heath because of the king’s scheme to take London in their absence. Later, France’s help in bringing down King John was on condition that the French Dauphin would take the crown of England. However, the succession of John’s nine-year old son Henry in 1216 stymied that plan.

The subsequent struggle between Henry and the barons reached crisis point in the summer of 1263, when Simon de Montfort was effectively ruling the kingdom. As the Earl of Gloucester marched on London to demand the restitution of lands seized from the barons, so Henry hurried to Windsor raising his own formidable force as he did so. Having his overtures of peace refused, Gloucester invited the king to give battle on Hounslow Heath, to which the king duly assented. But finding no army there to resist him, Henry stayed awhile before marching off.

Hounslow Heath became a popular stopover point for both sides during the Civil War. James, as Duke of York, knew it well from his boyhood and recognised its strategic value so close to London. Just weeks after his coronation, he assembled his new standing army there.

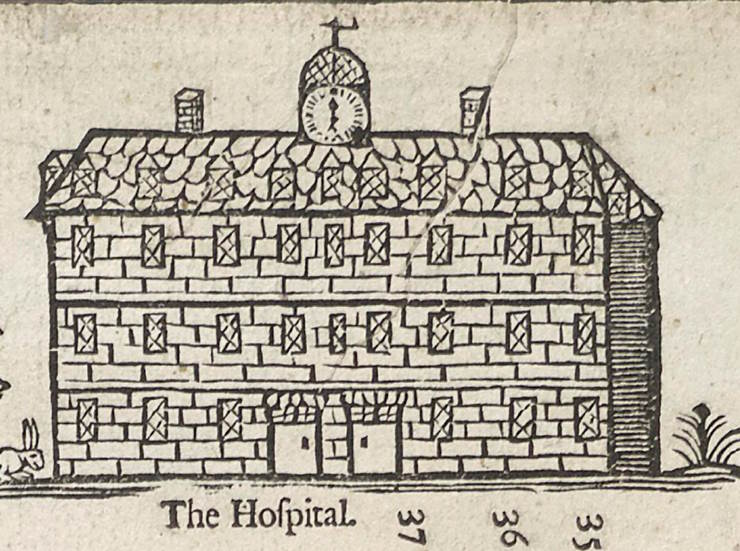

It comprised the best paid and equipped military force in Europe, whereby Britain would no longer be wholly reliant on the hire of foreign mercenaries and reservists in times of war. In this, Hounslow Heath became an immediate success as a training and public exhibition ground, and the perfect location upon which to build a citadel for use in times of civil unrest. Key to this undertaking was an impressive hospital designed by Sir Christopher Wren. It underlined James’ compassion for the common soldier with whom he had served alongside for most of his life.

Other permanent buildings included a huge grain barn and an industrial bake house used to service the encampment efficiently and economically. All else was of a temporary nature, dismantled and packed away at the end of each season. Included were stables for the horses, another unrecorded, unexpected, and unprecedented display of munificence at a time when the traditional policy of field management was for the animals to be tied at intervals to a rope on a common picket line in the open, where valuable feed was spoiled or trampled underfoot.

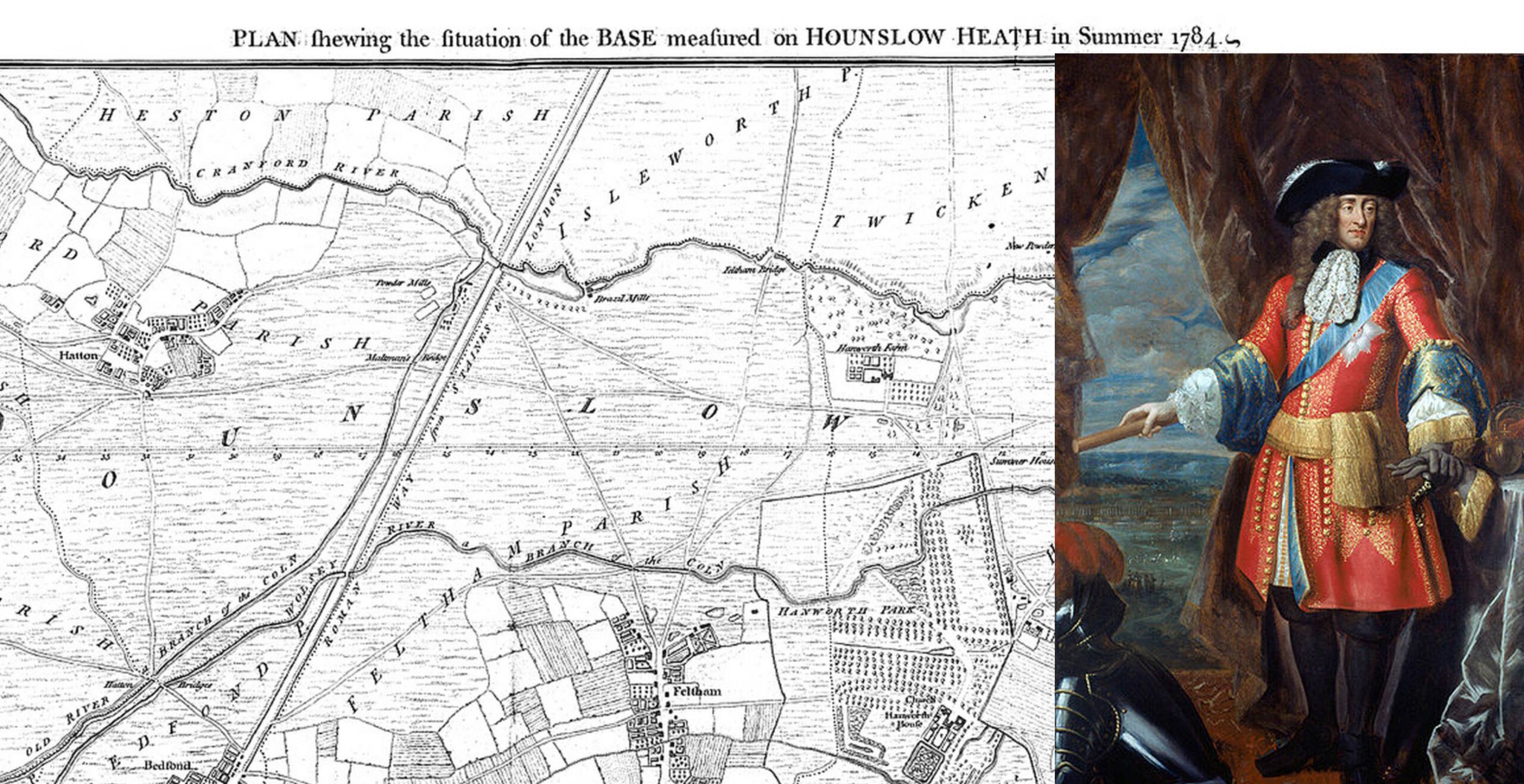

The full extent of James’ encampment covered three miles, which is today split between the London boroughs of Richmond upon Thames and Hounslow. The site of the Queen’s Perspective House is absorbed into Richmond’s largest public housing estate at the furthest extent of the borough. This opulent royal box once overlooked the full splendour of the entire British army undertaking precision military displays and dramatisations of what it was capable of doing, and how it was trained to do it.

A line of great kettle drums to the rear of the field joined trumpets, fifes and bagpipes used since the 14th century as instruments of battlefield communication. These signals accompanied the precise and complicated geometric movements of Musket and Pike, as an entertainment effectively signalling the birth of the military tattoo as we know it.

The first to follow James’ example was the ‘Grand Military Tournament & Assault at Arms’ staged at the Royal Agricultural Hall in Islington in June 1880. Including much the same programme of competitive displays, historic pageants and battles, it evolved into The Royal Tournament that went on to be held by the British armed forces annually until 1999 and is now familiar as the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo.

James II’s tour de force expressing his wider endeavour of returning the country to Catholicism failed to bolster what was fast becoming an uncomfortable monarchical regime. The 1687 encampment saw a huge mound built on Hounslow Heath representing Buda Hill, the ancient seat of the Turkish capital re-taken by Christian forces in 1686. James’ stunning re-enactment of The Great Siege attracted many thousands of spectators eager to witness Buda Castle pounded into submission by the big guns of the Holy League Army. The whole spectacle was recorded in an expansive series of drawings by Dutch artist Willem van der Velde. Yet, James’ overt demonstration of Papal Power only served to fuel the plan to oust him as king.

‘Buda Hill’ survived as a nondescript gravel heap until the early 20th century when it was cleared and rebuilt with the detritus of a fast-expanding capital. Across the road lies an industrious recycling yard, taking the footprint of King James II’s lavish quarters and close court. Only the roundabout intersecting the A316 Great Chertsey Road evokes in name the Hospital built by James. It survived into the reign of William, Prince of Orange, who was invited to invade Britain and restore a Protestant crown, which he did in The Glorious Revolution of 1688.

The Camp on Hounslow Heath is a long overdue examination of a much neglected local landscape, an overlooked passage in the history of the British army, and an underreported chapter in the Royal House of Stuart. This 209 page illustrated history is published by the Borough of Twickenham Local History Society and available to buy online: http://botlhs.co.uk/portfolio/107-the-camp-on-hounslow-heath/ or from bookshops: ISBN 9781911 145073. Price £9.00.

Ed retired early from the BBC and took a Master’s Degree in Local History. His subsequent eclectic mix of books includes walking London’s Roman wall to a lost film factory. He lives in Twickenham, where he enjoys rugby and is chair of the Local History Society and helps manage the Twickenham Museum.

Published 22nd August 2023