With the busyness of modern life, it’s easy to forget that, in London, you’re surrounded by the past almost everywhere you go.

In the big landmarks – Westminster Abbey, the Tower, the Houses of Parliament – history makes its presence boldly known. But elsewhere, away from the throngs of camera-happy tourists, it lingers more tentatively and sometimes hides. It’s with the wooden eaves and slate roofs behind brasher steel and glass structures, medieval churches down long quiet alleys and old engravings high above bright and glitzy shopfronts. The remains of Roman forts, Tudor townhouses and Victorian slums are all beneath your feet; you walk only on modernity’s latest concrete crust.

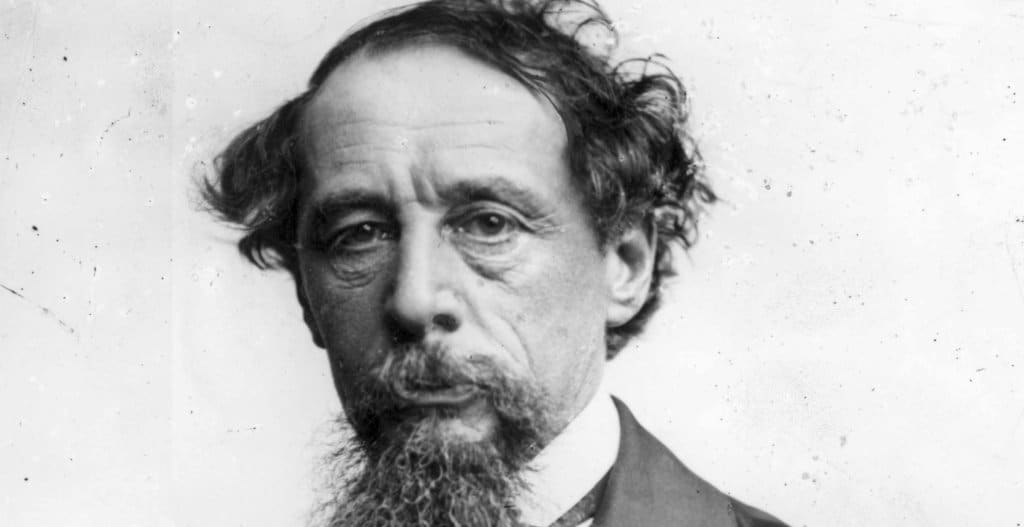

Over in Farringdon, a short distance from the high-rise obelisks of the Square Mile, people hurry with their hot Costa coffee cups in one hand and their iPhones in the other. Most don’t realise that Charles Dickens trod these streets daily or that the sights, smells, atmosphere and people he saw and spoke to on them fed his imagination. In a letter from August 1846, he described them as “a magic lantern” lighting the “toil and labour of [his] writing, day after day”. If you look closely enough, there are places where that lantern still glows.

To this day, 48 Doughty Street is The Charles Dickens Museum, an immaculately preserved Georgian townhouse and capsule of Dickens memorabilia and objects he would have known. He lived here between April 1837 and December 1839, a man in his late twenties with his new wife Catherine and a growing family, beginning to build what would become a reputation as one of the most talented of Victorian novelists. Mostly in his study on the first floor, at the back of the house overlooking the garden, he completed Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby.

On most days, Dickens would tread the pavements, finding inspiration everywhere. Just off the Farringdon Road, The Betsey Trotwood pub rises up painted blue and prominent to remind passers-by of the fictional aunt of David Copperfield and of the Dickensian past which still survives here. On the left, Pear Tree Court is reported to be where Dickens imagined the Artful Dodger and his chum Charley Bates pick Mr Brownlow’s pocket right before Oliver’s eyes in Oliver Twist. To this day you can picture the front of the book shop and the tall, respectable Victorian gentleman turning round as the boys “scud away at such a rapid pace”.

Continue down Farringdon Road, cross Clerkenwell Road and pass through Hatton Garden and you’ll come to Saffron Hill. In Dickens’ day, this was an abyss of slums where large families crowded together in cramped back-to-back dwellings with poor sanitation and minimal food and where crime was rife. In Oliver Twist, the Artful Dodger leads Oliver through these parts to Fagin’s Den on Feld Lane: “the street was very narrow and muddy, and the air was impregnated with filthy odours”. These labyrinths of deprivation were razed to the ground between 1863 and 1869 when the nearby Holborn Viaduct was built, but their legacy may remain in the names of the streets which Dickens would have known. It’s thought that particularly foul London streets and alleys were often given deliberately sweet-sounding names to conceal their squalid reality. You can therefore imagine how pleasant the bucolically named “Lily Place” just off Saffron Hill may have been in the mid-nineteenth century …

At the junction of Old Bailey and Newgate Street, Newgate Prison dominated the landscape. Today its only surviving wall stands at the back of Amen Court, but before it was finally demolished in 1904 and replaced by the Central Criminal Court, its reputation for harsh punishment and brutal conditions was legendary. The eighteenth-century novelist Henry Fielding – whose novel Tom Jones Dickens reportedly enjoyed as a boy – described Newgate as a “prototype of hell”. From the number of times the penitentiary features in Dickens’ work – from one of his earliest published pieces, ‘A Visit to Newgate’, to the trial scenes of Charles Darnay in A Tale of Two Cities and of Magwitch in Great Expectations – Dickens was absorbed by the horror of the place, which he would have seen, stuffed with prisoners, staffed by brutal keepers and where large crowds gathered to watch public executions until 1868.

You’ll have been aware of it for some time now, because its famous grey dome is visible from everywhere, but as you continue down Newgate Street you’ll arrive at the foot of St Paul’s Cathedral. Still an iconic landmark on London’s skyline, in Dickens’ time it was the tallest building in the city. For the writer making his way through the bustle of the lively and corrupt characters on the streets, yards and courts below, it would have seemed at the centre of most things. In Master Humphrey’s Clock, Dickens describes Master Humphrey going up to the top of the cathedral to take in the views beneath it: “Draw but a little circle above the clustering house tops, and you shall have within its space everything with its opposite extreme and contradiction, close beside.”

Carry on to Gresham Street via Gutter Lane and you’ll find yourself where the boy Dickens first arrived in London. Today’s 25 Wood Street was once The Cross Keys Inn. In 1822, a coach brought Dickens to London for the first time, from Chatham in Kent, “packed in like game” in the uncomfortable horse-drawn vehicle.

Along Gresham Street to the busy cross-roads just in front of the severe-looking stone portico of the Bank of England. Cornhill flows from here and has several links to Dickens. The churchyard of St Peter’s Cornhill is now mostly empty, set back behind the busy street in the quiet shadow of the church tower and the surrounding buildings. It’s the church Dickens imagined when, in Our Mutual Friend, Lizzie Hexam meets Bradley Headstone. He describes it as it was then: “The court brought them to a churchyard; a paved square court, with a raised bank of earth about breast high, in the middle, enclosed by iron rails. Here, conveniently and healthfully elevated above the level of the living, were the dead and the tombstones”.

Double back on yourself and proceed along Cheapside via Bank and then Poultry, and you’ll return to St Paul’s Churchyard. Here stands Temple Bar. Londoners sauntering idly about it or lovers stealing kisses underneath it today may be oblivious to the significance of the structure above their heads. This imposing stone archway was originally designed by Sir Christopher Wren and, when it stood where the Strand meets Fleet Street, it was the gateway to the City of London for two hundred years. The name of the monument has its origin in its proximity to the Temple, where the guilds of lawyers organised into what would become the Inns of Court, in an area now dubbed “Legal London”. In Bleak House, Dickens describes Temple Bar as “a leaden-headed old obstruction”, a reference to how the edifice was once a big obstacle to the flow of traffic and therefore derided as a symbol of the activities of the City of London Corporation.

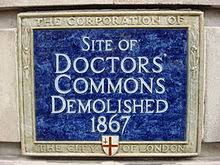

Our walk ends on the other side of St Paul’s where, if you advance along Godliman Street to Queen Victoria Street, you can find a blue plaque which marks the site of the former “Doctors’ Commons”. In Dickens’ day, five courts dealt with admiralty, matrimonial and ecclesiastical issues here. He even worked here, between 1828 and 1832, and features it in David Copperfield as the place where David first meets his future wife, Dora Spenlow.

Peer around that corner, glance up at that window, venture down that out-of-the-way alley. Look closely enough at the buildings and monuments and streets between Farringdon and Bank, and it quickly becomes apparent that what inspired Dickens’ genius is still here, almost two hundred years on. If his own environment – much of it shabby, sordid and poor – propelled him to the heights of immortal greatness that it did, then perhaps our own surroundings can lift us to equivalent heights today.

By Toby Farmiloe. Toby Farmiloe may physically live in London, but his heart and spirit reside firmly in the countryside and, more often than not, in a past century. Born and bred in East Sussex, he has always loved history.