The recent wilful destruction of historic monuments by IS in Syria brought vividly to mind the many medieval ruins in the British Isles that reflect the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the sixteenth century. While the motivation of Henry VIII may have been different, the end result was the same: the irreplaceable loss of heritage that had shaped our social fabric, in a deliberate act of vandalism on a breathtaking scale. In his acrimonious break with Rome and the Catholic Church, the King directed his wrath primarily at the magnificent abbey and priory churches, which he considered the most potent symbol of ‘popery’. Yet, among the wholesale devastation of great feats of engineering and architecture, some were saved by the local populace for the parish, though not without a heavy exaction by the Treasury, while the broken walls of others still reach defiantly for the sky.

The inquisitive amateur historian or committed Christian need not look far to find evidence of monastic settlements in all parts of Britain, but should first head to Yorkshire where around one hundred monastic settlements were established in ‘God’s own country’, often in beautiful secluded dales, many still far from the madding crowds. As you walk on sacred ground among the quiet stones, your imagination will find it easy to reconnect with the former splendour of these great places of worship.

There can be few more spectacular views of an English monastic site than that of Rievaulx Abbey of the Cistercian Order from the terrace high above. Tucked away in a hollow under the steeply wooded hillside, the tall, skeletal walls of the church soar above the little River Rye in Ryedale in perpetual defiance of the destructive power visited upon its hallowed halls by man and the elements. In the earliest accounts of Rievaulx, the site was described as the “awe-inspiring and solitary place”, a description that has stood the test of time well. No matter how long and tiring the journey, a visit to Rievaulx should be of the highest priority and the massive church the first place to pause at in humble admiration. Its arcades of clustered columns and Gothic arches reaching up to the windows of the triforium and clerestory enrich the church with an elegance found in few others.

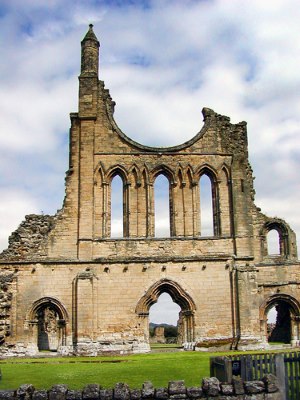

The second great Cistercian abbey was that at Byland (above), set in quiet meadows in the shadow of the Hambledon Hills with the sound of bells from Rievaulx. The soaring west front with its broken 8m (26ft) diameter rose window is one of the most recognisable landmarks in the county. Its appeal is enhanced still further by the mellow tones of the honey-coloured sandstone, which imbues the ruins with extra warmth. But before the monks could commence this architectural masterpiece, they had to clear and drain this thickly wooded and swampy site. The beautiful and lofty west front standing almost alone is testimony of their undoubted skills in engineering. It was not long before Byland was hailed as one of the three greatest monasteries in the North. Particularly noteworthy are the green and yellow medieval floor tiles with geometrical designs (below), which were used throughout the church and can still be found in situ in parts of the south transept and crossing.

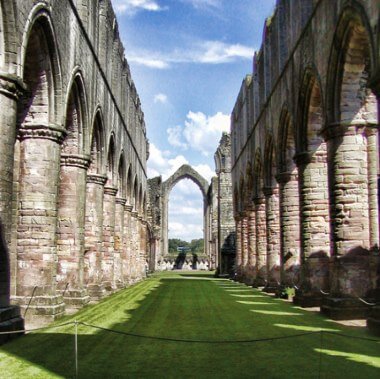

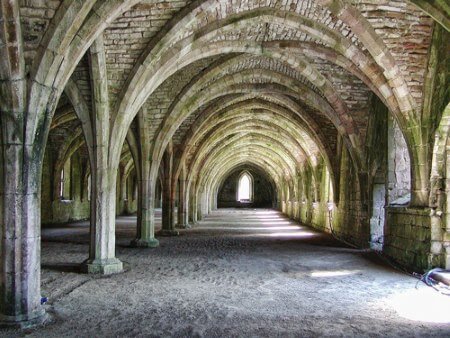

The equally impressive ruins of Fountains Abbey are a delight to the eye, both in terms of its picturesque setting and architectural excellence and diversity. But when the Benedictine monks from York arrived in this remote valley by the River Skell, it was described as a place “more fit for wild beasts then men”. Extreme hard work was the order of the day and the abbey eventually became wealthy from the sale of wool, quarrying of stone, horse breeding and iron and lead mining. But religious life was not neglected and soon after its foundation in the mid-twelfth century, the monks embarked on the construction of the grandest abbey of its time. Although it too was a house of Cistercian monks, the cruciform church was more in keeping with the Order’s avowed austerity. It was, however, an impressively long edifice measuring 107m (351ft). The ruins present an instructive overview of a large monastic complex from conventual and domestic buildings, to an infirmary for the sick and ageing, and a monks’ workshop on the hillside. The most striking features are the Chapel of the Nine Altars, so named after the nine altars that stood side by side along the wall, and the remarkable vaulted cellarium (below), of the same length as the church.

Broken these silent stone walls and defaced statuary may be today, but in one’s mind their stories and those of the monks walking among the ruins, praying, contemplating and working every day of their lives over a period of four hundred years, can still be a vivid experience not to be missed.

There is so much to discover and explore, and evidence of monastic foundations may be just around the corner. They may impress with reconstructed grandeur or faded glory, sometimes languishing in neglected solitude. A visit to www.powerandpiety.co.uk will encourage and inform, with none ignored or forgotten.

All Photographs © www.powerandpiety.co.uk