Any visitor overhearing a conversation between two native speaking Englishmen or women could be excused for wearing a strange quizzical expression on their faces as they attempt to interpret the words that they have just heard …“I’m told he’s just got the sack for being a Peeping Tom, but then I’ve always said he’s as mad as a hatter.”

Many of these strange phrases and expressions have their roots firmly established in the rich history of the English people themselves.

Get The Sack – Thought to originate from when an employer would hand a sack to an unwanted tradesman. The sack would have been used to by the tradesman to load his tools into as he subsequently left to search for a new job.

As Mad As A Hatter – The Mad Hatter is of course a fictional character immortalised by Lewis Carroll in his famous Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The phrase however is believed to originate from the Leicestershire area of the East Midlands of England. In a more fashion conscience age, Leicester was a renowned manufacturing centre for the hat industry and the expression derives from an early industrial disease. In the poorly ventilated workshops of the 1800’s it was impossible for hat makers to avoid inhaling the fumes from the mercury used in the felt curing process. Over time this heavy metal accumulated in the body, gradually affecting both kidney and brain. Still known today as ‘Mad Hatters Syndrome’, typical symptoms of mercury poisoning include trembling or ‘hatter’s shakes’, loosening of the teeth, distorted vision, slurred and confused speech, memory loss, depression and hallucinations.

Dead As A Doornail – This expression can be traced back to 1350, but could be even older. In the days before screws were commonly used in carpentry, nails secured one piece of wood to another. Unlike screws however, nails could often loosen over a period of time. To prevent this, it became common practice, particularly on large medieval doors, that when a nail was hammered through the wood it would be flattened or clinched on the inside. The process of flattening the nail would mean that the nail would be ‘dead’ as it couldn’t be used again.

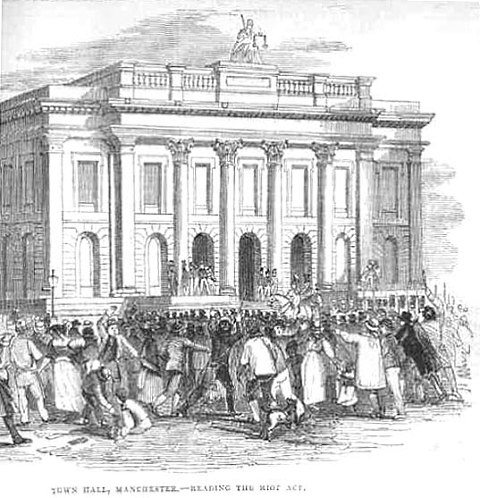

Read The Riot Act – The Riot Act was first introduced in 1715. It allowed local authorities the power to disperse unlawful gatherings of more than 12 people on the streets of England’s towns and cities. The Act was passed by a nervous government in response to the growing threat from Jacobite Catholics opposed to the new Hanovarian King George I. The law required the local magistrate to read a proclamation aloud to the crowd that included the following stern warning;

“Our sovereign Lord the King chargeth and commandeth all persons being assembled, immediately to disperse themselves, and peaceably to depart to their habitations, or to their lawful business, upon the pains contained in the act made in the first year of King George, for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies. God save the King”

Failure to observe such a warning was severe and could include imprisonment with hard labour for up to two years.

Carrying Coals To Newcastle – Thought to date from the 1600’s, what could be more pointless than to carry coals to Newcastle upon Tyne? Located on England’s northeast coast, Newcastle was the major port through which coal was exported from the surrounding coal rich seams and pits.

Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the 1800’s

Flash In The Pan – The expression denoting all show with little substance derives from the late 17th century and the days of the flintlock musket. A small charge of gunpowder loaded into a pan was intended to ignite when struck by the flint and light the main charge of powder thus propelling the musket ball down the barrel and into the advancing enemy. If the main charge failed to ignite the gunpowder loaded into the pan flared up without a bullet being fired and this was known as a ‘flash in the pan’.

Go Off At Half-Cock – Generally meaning to act prematurely, this is yet another familiar expression that can be dated back to the age of the flintlock musket. The spring on the striking mechanism that creates the spark to ignite the charge and fire the musket would normally be set to what is known as a full-cocked position when the musket was ready to be used in anger. A safer alternative was to leave the musket charged with powder and shot but in state were the spring was not fully tensioned, known as half-cocked. A musket would generally only ‘go off at half-cock’ by mistake, or if the musketeer was acting in a state of panic.

Nail Your Colours To The Mast – A naval expression thought to date from at least the early 1800’s. In naval battles, flags or colours were generally lowered as a signal of surrender. In ‘nailing your colours to the mast’ you are therefore proudly showing which side you represent, or the beliefs you hold, and demonstrating your intention never to surrender that position.

Steal My Thunder – In the early 1700’s the literary critic and playwright John Dennis developed a new technique which could be used to simulate the sound of thunder in theatrical productions. He later employed the technique in one of his own plays, ‘Appius and Virginia’. Whilst the sound of thunder appears to have lived up to expectation, the play unfortunately did not and was promptly closed. Some months later whilst watching a production of Macbeth, Dennis recognised to his horror that his new technique of making thunder had been, let us say ‘incorporated’. Jumping to his feet he exclaimed to the audience “They will not let my play run, but they steal my thunder”.

Peeping Tom – So who was this famous voyeur named Tom? According to legend, it appears that Tom lived in the English Midlands city of Coventry around the 1040’s. He is associated with the legend of Lady Godiva, and her naked ride through the streets of Coventry, in an attempt to convince her Anglo-Saxon husband Leofric, Earl of Mercia, to reduce the harsh taxes he had imposed on the town’s poor. In her support, the townsfolk had all agreed to avert their eyes as Godiva passed by, all that is apart from Tom, who apparently couldn’t resist just one little peep!

Peeping Tom – So who was this famous voyeur named Tom? According to legend, it appears that Tom lived in the English Midlands city of Coventry around the 1040’s. He is associated with the legend of Lady Godiva, and her naked ride through the streets of Coventry, in an attempt to convince her Anglo-Saxon husband Leofric, Earl of Mercia, to reduce the harsh taxes he had imposed on the town’s poor. In her support, the townsfolk had all agreed to avert their eyes as Godiva passed by, all that is apart from Tom, who apparently couldn’t resist just one little peep!

And so to end with Sweet Fanny Adams, or nothing, poses the obvious questions …Who was Fanny Adams, and was she really that sweet? Fanny Adams was in fact the eight-year-old victim of a particularly vicious murder close to the small market town of Alton in Hampshire, England in August 1867. Her dismembered body was found in a nearby field. Newspaper headlines of the day concentrated on the innocence of her youth and such was the coverage that all in England would have known about ‘sweet’ Fanny Adams. It appears that it was some several years later that the expression sweet Fanny Adams was used perhaps in an attempt to clean up the alternative version, that of sweet F.A.

Published: 18th June 2015