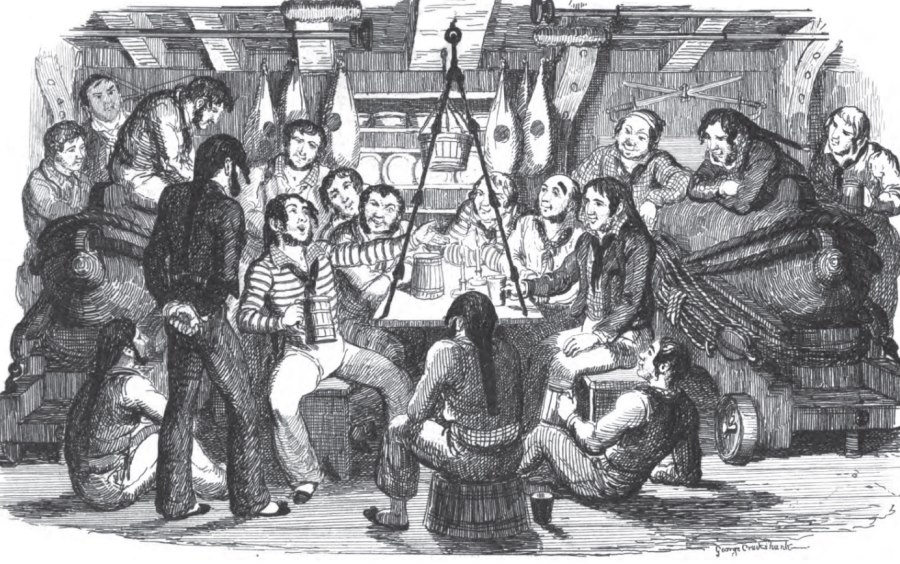

The origins of the traditional Sailors’ Sea Shanty have been lost in the midst of time. Traceable from at least the mid-1400s, the shanty hails from the days of the old merchant ‘tall’ sailing ships.

The shanty was quite simply a working song that ensured sailors involved in heavy manual tasks, such as tramping round the capstan or hoisting the sails for departure, synchronised individual efforts to efficiently execute their collective task, i.e. simply making sure that each sailor pushed or pulled, at precisely the same time.

The key to making this happen was to sing each song, or shanty, in rhythm.

More often than not there would be a solo-singer, a shantyman, who would lead the singing of the songs with the crew joining in for the chorus.

Although the actual singing of these songs may date back several hundred years, the origin of the word ‘shanty’ is more recent. Only traceable back via the dictionaries to around 1869, there are a number of variations in the spelling of shanty, including chantey and chanty. There is also some debate as to the actual derivation of the word shanty, with some citing the French word “chanter”, ‘to sing’, with others proposing the English “chant”, synonymous with those religious Gregorian chants .

Getting down to the nitty gritty technicalities of these sailors working songs though, there are indeed two major variants of the shanty, known as the Capstan Shanty and the Pulling Shanty.

Similar to the marching songs of those soldier boys, the Capstan Shanty was sung to accompany work of a regular rhythmical nature, such as tramping round the capstan in order to raise the heavy iron anchor. With no special requirements other than to hold the attention of – and of course amuse – the sailors, virtually any ballad could be adopted for this purpose, provided it was delivered at the required tempo and preferably with some ‘mucky’ innuendo… “Farewell and Adieu to you, Ladies of Spain,” would perhaps be one famous example.

The Pulling, or Long Drag, Shanty however, required something a tad more specialised to accompany the spasmodic and irregular work involved with raising the yardarms or hoisting the sails. With work of this type, as well as keeping the attention of the sailors it was also necessary to ensure that all pulled together at exactly the same time, with a sufficient gap in-between to regain a fresh grip on the rope, as well as gathering breath before the next exertion. Normally this type of ‘call and response’ shanty involves a solo shantyman singing the verse with the sailors joining in for the chorus. Using the shanty “Boney” as an example;

Shantyman: Boney was a warrior,

Crew: Way, hey, ya!

Shantyman: A warrior and a terrier,

Crew: Jean-François

In their response to the shantyman, the crew would pull together exactly on the last syllable of each line.

Without doubt though, the main attraction of either shanty was to bring a sense of humour and spirit of fun to the hard manual tasks that the sailors encountered each and every day on the long sea voyages that they endured. It is said that having a good shantyman aboard was worth a couple of extra hands, and as such this valuable asset often enjoyed special privileges such as lighter duties, and / or perhaps an extra tot of rum.

The arrival of those new-fangled steamships however, brought an end the days of the tall ships and the need for raw manpower. And so, by the turn of the 20th century, the sounds of the sea shanty were seldom heard and had almost been forgotten, but thanks to several notables including Cecil James Sharp (1859-1924), we have been left with legacy of more than 200 of these sailors’ working songs.

Travelling the length and breadth of the nation’s coastal trading towns and fishing villages, Sharp interviewed retired old sailors and noted down both the words and music of those traditional working songs in a number of collections including ‘English folk-chanteys : with pianoforte accompaniment, introduction and notes’, first published in 1914.

In more recent times, these songs are brought to life each summer by groups of shantymen performing in seafaring ports (and pubs) up and down the country in order to preserve and share with others this important part of our maritime heritage.