Dating back to the fifteenth century, Plough Monday marked the beginning of the English agricultural year just as the celebrations of the Twelve Days of Christmas came to a conclusion.

Every year, Plough Monday was marked as the first Monday after the Epiphany on the 6th January and was observed by communities up and down the country.

After the traditional festive period had been enjoyed and celebrated at home, Plough Monday marked not only the beginning of the agricultural year but the start of people returning to work and their normal routine.

The day prior was known as Plough Sunday, which was commemorated in local churches regardless of denomination. As part of the service, a ploughshare was taken into the church and prayers were made for the next year with blessings dedicated to the land, the people who toll the land and the tools they required to produce a good and abundant harvest in the year ahead.

The ploughs were cleaned and adorned with decorations to take into the church and receive the blessings.

Moreover, celebrations also included what was known as a Plough Light which was a ceremonial candle lit on the day and kept alight as a symbol of good blessings and a promising farming season ahead.

The following day, Plough Monday, saw the decorated plough taken through the village whereby donations were made by the locals that were to be used to maintain the Plough Light all year round. These donations were later used to contribute towards community events such as Molly dancing.

The tradition itself was thought to have dated back to pre-Christian pagan traditions which would have marked the beginning of a new season.

Moreover, the celebrations were not evenly distributed across the country. The majority of communities who recognised Plough Monday on their calendar were predominantly from Lincolnshire, East Anglia and Yorkshire. Its prevalence outside of these locations was diminished as the tradition was concentrated in the northern part of the country as well as East England. That being said, records show how Plough Monday was observed in counties across Britain including down in the southern tip of England in Cornwall, as well as Warwickshire and Worcestershire.

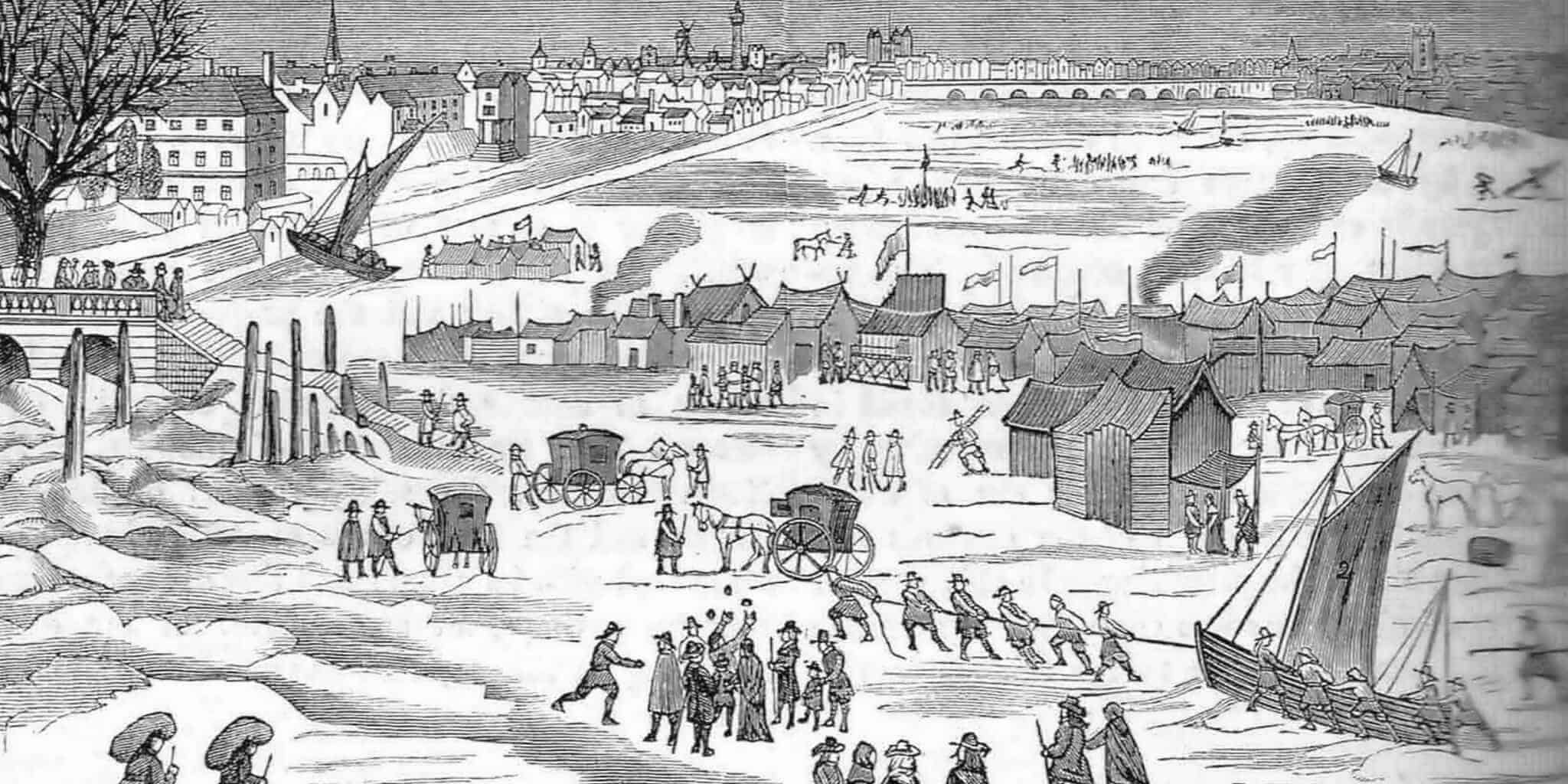

As a result of the regional distribution, celebrations varied depending on location but generally all festivities were marked by the procession of a plough through the community and the collection of money.

In some cases, music formed an integral part of the revelry, whilst in Norfolk a boiled suet pudding comprised of a meat and onion mixture was made and eaten on Plough Monday known as ‘Plough Pudding’.

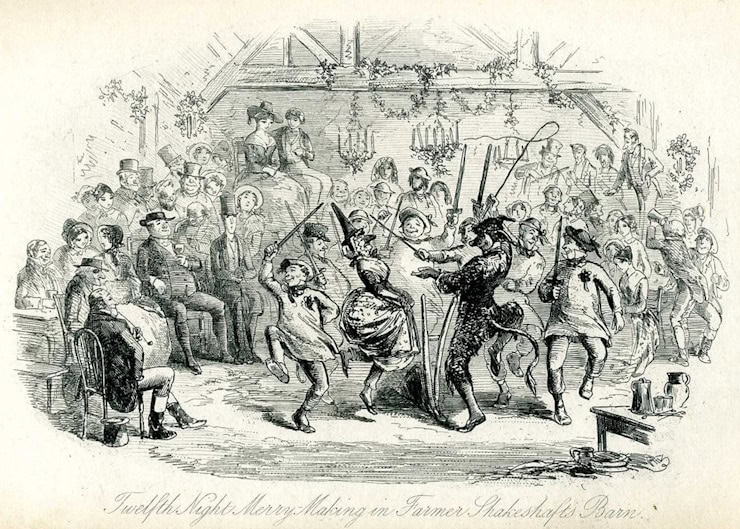

In the Isles of Scilly, the locals would partake in cross-dressing and then pay their neighbours a visit. Those participating in the procession were often dressed in costumes, with some cross-dressing as females. They were known as the Plough Boys, however each region had different names to refer to these eccentric cast of characters including Lads, Jacks and Stots.

Other unique aspects of this tradition included the role of the ‘fool’ in the procession with an outfit that was particularly pagan in style, using the tail of animal which hung from the costume. The other part of this act was normally played by an old woman who dressed up in an unusual outfit and was known by the name Bessy. These characters would proceed through the local streets shaking their box for donations from the spectators.

If someone was unwilling to make a contribution, one of the Plough Boys would turn up at their front door with their plough and cut a deep furrow into their front door.

These idiosyncrasies were all part of the festivities and were very community driven, as people living in rural areas were dominated by the agricultural year which dictated the schedule for farmers.

By the time of the Reformation, the tradition of the ‘plough light’ and the money raised for the church appeared to peter out with the changing religious landscape of the country. Moreover, the religious aspects of Plough Monday were suppressed, forcing people to retreat into their private spaces to continue observing the festival.

Whilst the practise continued to endure for many centuries, the advent of revolutionary farming technology in the nineteenth century stunted the festivities. Whilst agricultural workers existed in smaller numbers, they were also better paid and thus the need for collections continued to dwindle.

By the 1930s, a few Plough Monday celebrations were still being practised, however the outbreak of the Second World War saw most of these traditions die out.

A couple of decades later, Plough Monday experienced something of a revival and in 1977, the Cambridge Morris Men revived molly dancing on the day. Moreover, in some parts of northern England, traditions using the plough and community collections persist.

Perhaps most notably, in Cambridgeshire, the annual celebrations were revived in 1980 and observed by a procession known as the Whittlesey Straw Bear Festival. On the Saturday before Plough Monday, a performance of folk dancers accompanied by music, with many in elaborate costumes, heads down the streets in a parade.

Thus the historic traditions of Plough Monday have experienced a revival with enthusiasts re-enacting this historic British festivity.

Steeped in the history of the British agricultural community, Plough Monday was an important date in the calendar, marking not only the end of Christmas celebrations but the beginning of hard work and a long and physically strenuous year for farmers up and down the country.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 30th December 2024.