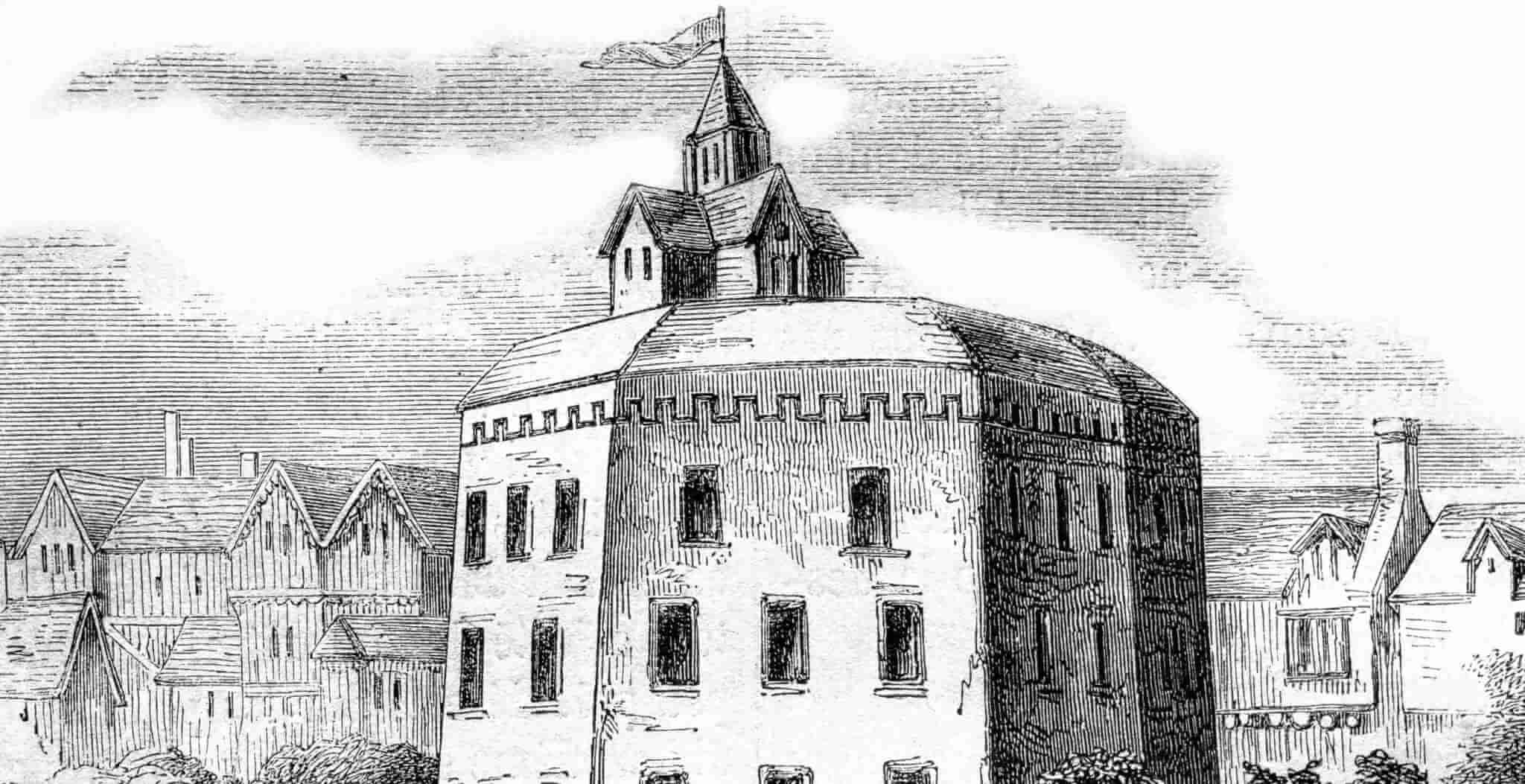

In the spring of 1796 Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the owner of London’s Drury Lane Theatre, announced the premiere of a previously unknown play by William Shakespeare. Vortigern was believed to be an early work of Shakespeare’s, set in fifth-century Britain.

Sheridan had thought some of the writing a little clumsy when he first read Vortigern, but he had dismissed his doubts, telling himself that it was probably a very youthful work. He had recently rebuilt his theatre and was heavily in debt – he needed a runaway success, and a new play by Shakespeare could hardly fail to draw the crowds. The premiere was scheduled for 2 April 1796, and two of the most famous actors of the day, John Philip Kemble and his sister, Sarah Siddons, were given the leading roles.

Sheridan should have trusted his instincts. The real author of Vortigern was not Shakespeare, but a nineteen-year-old boy. William-Henry Ireland, the son of a London engraver and antiquarian, had dreams of becoming a writer. Instead, he created one of the greatest literary forgeries of the century, somehow managing to convince Georgian society that he had discovered an entire cache of unknown Shakespearean manuscripts.

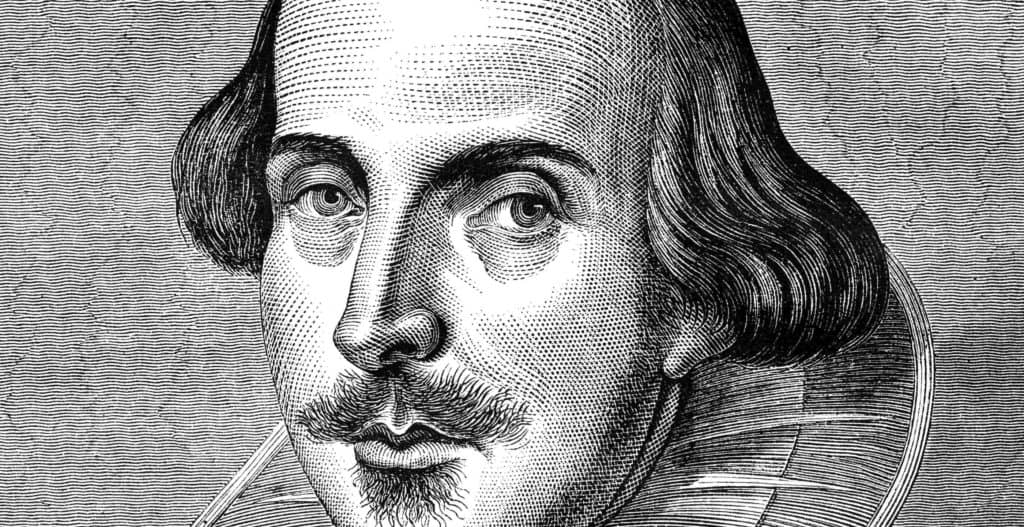

William-Henry Ireland

William-Henry was a troubled teenager. He had performed poorly at school, and his teachers had considered him stupid. His father, Samuel, had little time for the boy – but that all changed one day in December 1794, when William-Henry came home from his work in a lawyer’s office, and presented his father with a mortgage deed signed by William Shakespeare himself. Samuel, who had an obsessive passion for Shakespeare, was thrilled.

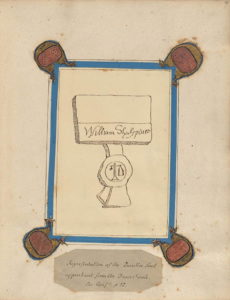

William-Henry claimed that the document had come from a collection of Shakespearean manuscripts, which had been found in a chest belonging to an acquaintance of his, referred to only as ‘Mr H’. The mysterious Mr H wished to remain anonymous, and had no interest in the papers.

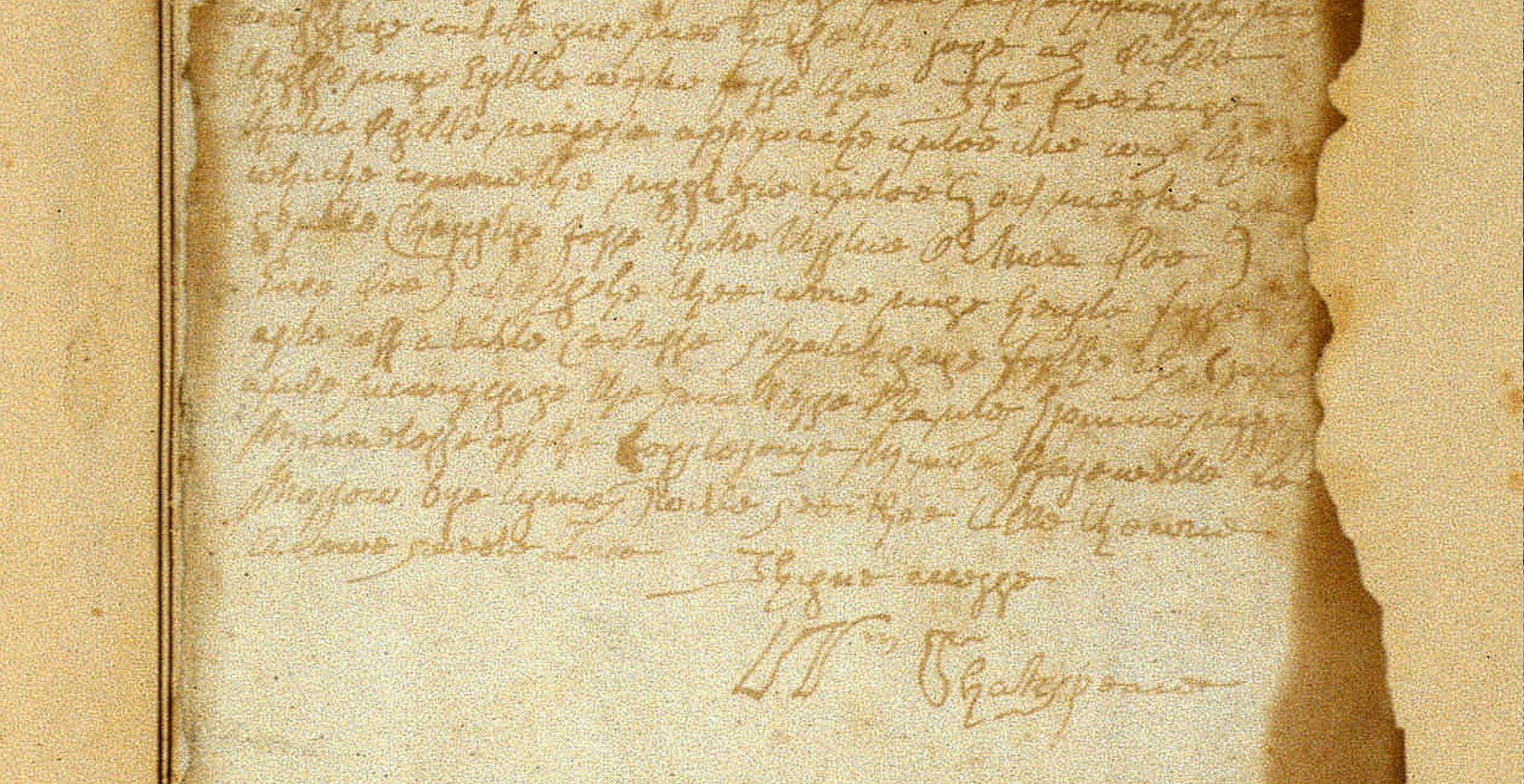

In fact, William-Henry had produced the document himself at his workplace, where he had access to materials from the Elizabethan period. He had cut out a piece of parchment from an old rent roll to create the deed, adding Shakespeare’s signature, which he had copied from a book. He used ink diluted with bookbinders’ chemicals, which turned brown when held close to a candle flame, giving the writing an antique look.

The invention of Mr H and his chest was William-Henry’s big mistake. If he had confined himself to just the one paper, all might have been well. However, Samuel, overcome by excitement, put pressure on his son to produce more of the hidden treasures. William-Henry felt compelled to continue, and Samuel began to invite his friends to the house to examine the documents.

Practically nothing in Shakespeare’s handwriting has survived. This had led to a belief in the eighteenth century that a repository of manuscripts must exist somewhere, and would be discovered one day. As public interest in the Irelands’ papers mounted, William-Henry worked manically, producing item after item from the ‘secret collection’. These included a love letter from Shakespeare to Anne Hathaway, a statement of Protestant faith, a letter from Queen Elizabeth I to Shakespeare, and a draft of King Lear. These revelations culminated in the announcement of the discovery of a complete manuscript of an unknown play: Vortigern.

Both the contents of the papers and the supposedly Shakespearean spelling became more bizarre as William-Henry dug himself deeper into the pit of his own making. The ‘statement of Protestant faith’ ends: ‘O cheryshe usse like the sweete Chickenne thatte under the coverte offe herre spreadynge Wings Receyves herre lyttle Broode …’

Shakespearean scholarship was less advanced than it is now, and forensic testing of documents had not yet been invented – but it still seems astonishing that anyone could have taken the documents at face value. There were some voices of dissent, but those deceived by the fraud included politicians, aristocrats, a number of leading scholars, and even royalty – the Duke of Clarence was a believer. Dr Johnson’s biographer, James Boswell, on seeing the papers, knelt and kissed them, exclaiming ‘thanks to God that I have lived to see them’. He died a few months later, still convinced that the documents were genuine.

Samuel Ireland

The newspapers publicised the remarkable finds, and people flocked to the Irelands’ house to see the manuscripts. Eventually, Samuel organised a standing exhibition, issuing tickets for set visiting times. In December 1795, he published the collected manuscripts – against his son’s wishes – and the tide began to turn. The leading Shakespeare scholar, Edmond Malone, who had not been allowed to examine the papers, denounced the documents as a daring fraud just two days before the premiere of Vortigern was scheduled to take place.

At the time, few people really knew Shakespeare’s plays. They were performed in heavily edited and adapted versions – King Lear was even given a happy ending to please the sentimental Georgian audiences. Nonetheless, as rehearsals had progressed at Drury Lane, Sheridan and his actors had realised that Vortigern could not have come from Shakespeare’s pen. However, it was too late to withdraw – although Sarah Siddons wisely developed a vague illness that prevented her from taking part in the premiere, which was a disaster. The audience laughed at the play, which did not survive its opening night. Reviews were scathing.

William-Henry was initially relieved – he must have been under enormous psychological strain for months – and he confessed publicly to the forgeries. He had naively imagined that once all was known, he would be admired for his ingenuity and writing talent, but he found himself disgraced as a fraud.

William-Henry Ireland had set out to impress his neglectful father, but found his life defined by a hoax that had spiralled out of control. He subsequently wrote numerous novels and books of poetry, but success eluded him. Samuel Ireland was believed by many people to have been complicit in the fraud. He stubbornly refused to accept the truth of William-Henry’s confession, and died in 1800 still insisting that the Shakespeare papers were genuine.

Elaine Thornton is a writer and the author of a recent biography of the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Giacomo Meyerbeer and his Family: Between Two Worlds (Vallentine Mitchell. 2021).

Published 13th December 2022