‘If the ravens leave the Tower, the kingdom of Britain will fall…’

An ominous legend, and one that requires a full time caretaker for the birds – in this case, the grandly titled Ravenmaster at the Tower of London.

Today Chris Skaife proudly holds this job. It’s not an easy job to land – like Chris, you’ll have to be a Yeoman Warder, a position which requires a minimum of 22 years in the military, an exemplary record, and the rank of warrant officer or above.

But the birds themselves cast the deciding vote. When the previous Ravenmaster, Derrick Coyle, saw that Chris was fascinated with the ravens, he decided to test their chemistry by putting Chris in the cages with them. Chris was deemed suitable by those most discerning judges. He studied under Derrick for five years before taking over the job.

Chris now looks after the seven ravens at the Tower (six by Royal Decree and one spare): Harris (Male), Merlina (Female), Munin (Female), Rocky (Male), Gripp (Male), Jubilee (Male), and the sisters Erin and Hugine. Most are quite young – Munin is the oldest, at 21 years old. The ravens come from breeders in Somerset, but two are wild – Merlina, from South Wales, and Munin, from North Uist in Scotland.

Chris tries to keep them all as wild as possible, giving them free rein around the grounds. New open-air cages have recently been erected, at Chris’s insistence.

The most difficult part of the job is the hours. Chris’s daily routine starts at first light, when he lets the ravens out, cleans their cages, and prepares their food – a ration of roughly 500 grams of meat a day, mainly chicken and mouse, in addition to whatever they nick off the tourists. They are out wild during the day, though he keeps an eye on them, and puts them to bed at nightfall.

Chris does all the normal duties of a Yeoman Warder, with the extra responsibility of looking after the ravens. A team of three helps him out, covering his off days when he’s not at the Tower.

The best part of the job, Chris insists, is the ravens themselves. He enjoys caring for them and bonding with them, and he is constantly fascinated by the scope of their inner lives. Ravens are extremely intelligent animals, with a complicated understanding of past, present, and future. In fact, university students visit the Tower to study raven behaviour and cognitive ability, which is thought to be similar to that of chimps or dolphins. If humans had brains relative to the size of ravens, Chris is fond of saying, our heads would be twice as big. All this intelligence, of course, leads to them being very curious – and sometimes naughty, stealing purses from tourists and hiding the coins all around the grounds.

Chris has a great relationship with all of the ravens, but they don’t all have a great relationship with him, attested to by various scars up and down his arms.

The ravens do occasionally try to escape. The birds can fly – Chris does not clip their wings (he hates that expression), he only unbalances their flight wings a little. Often they’ll fly around the White Tower or over the Thames before coming in to go to bed. Once, he lost Munin for seven days. He got a call from a man in Greenwich, wondering if the Tower had lost a raven. Chris talked him through catching her – a piece of chicken, a blanket, and some gloves – and then came and got her.

Though Chris doesn’t strictly believe in the legend of the Tower ravens, he can attest to their power to fascinate. He meets thousands of visitors who see ravens as symbolic or spiritual creatures, or simply as beautiful animals that they want to paint or draw. Chris shares his experiences with the ravens across social media, putting up pictures and videos almost daily.

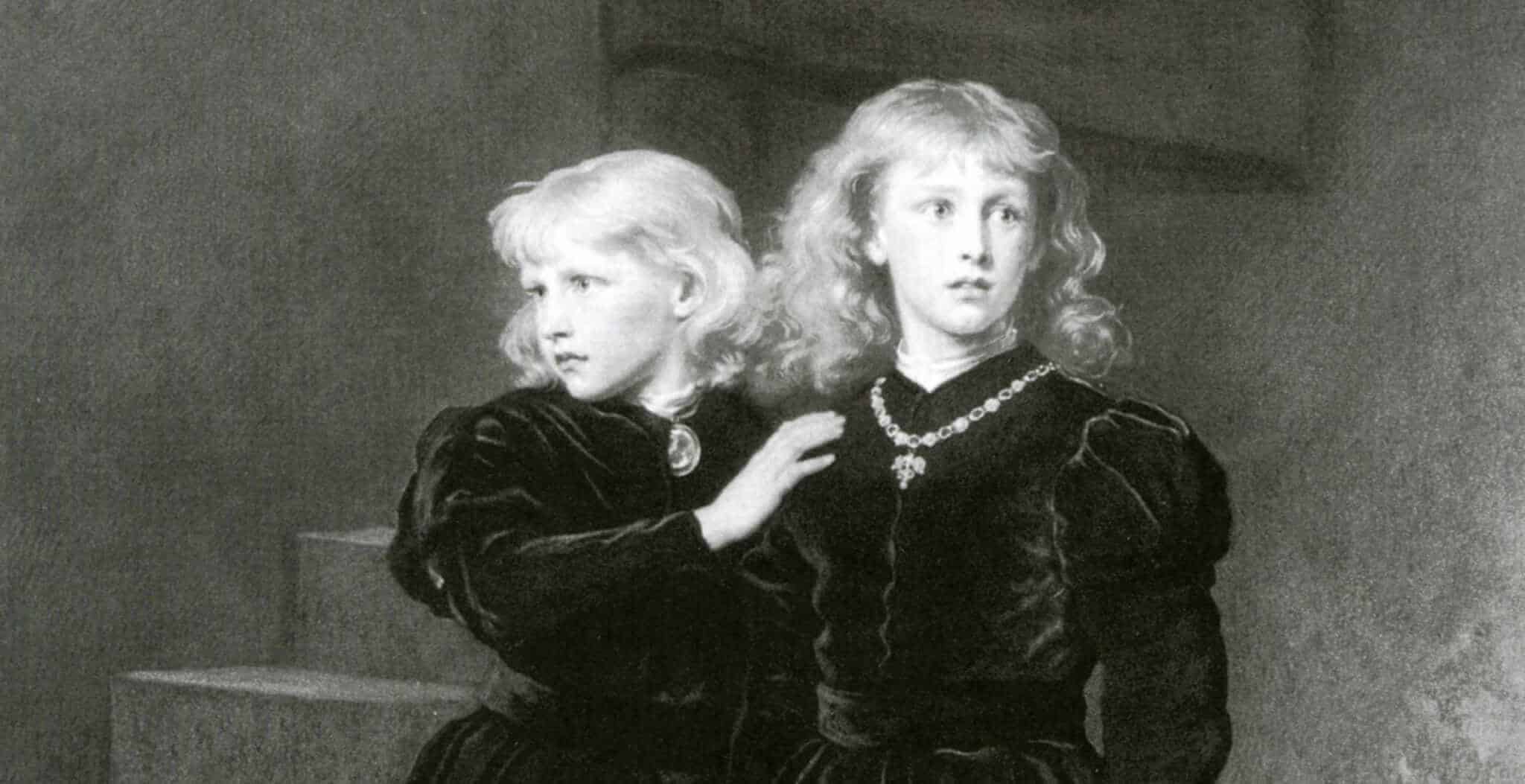

Where does the legend come from? It was once thought to be a Victorian flight of fancy. During the time of Charles II, the legend says, wild ravens still lived in London, and many had taken up residence at the Tower. Charles believed the superstition that ravens were a symbol of good fortune (perhaps due to their connection with King Arthur). When his royal astronomer, John Flamsteed, complained that the constant traffic of ravens made it difficult to observe the night sky, Charles opted to move the Observatory (to Greenwich) and keep the ravens at Tower.

However, the legend actually arose during WWII, likely as a response to the horrors of the Blitz. The first recorded reference to the legend dates to this period, and the first Ravenmaster was installed in the 1950s. (Chris is only the 6th person to hold the title.)

It seems fitting that such a powerful belief took hold in Britain’s darkest hour. As German bombing intensified and a real fear of invasion loomed, people sought out hope wherever they could find it. And as long as ravens still lived at the Tower, Britain could never fall.

Which makes the job of Ravenmaster all the more vital.

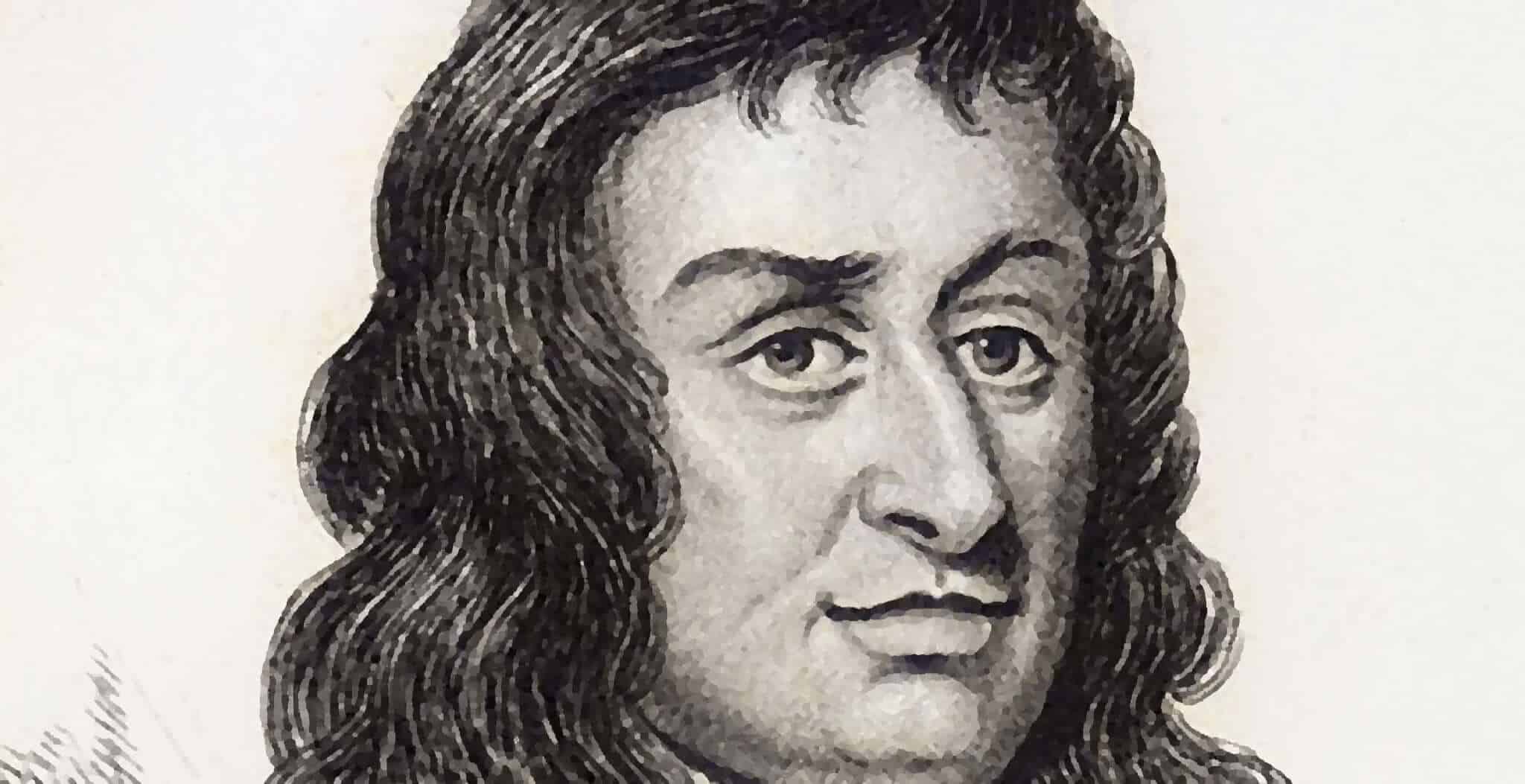

John Owen Theobald’s historical fiction novel, These Dark Wings, explores the legend of the ravens during the Blitz.