The concept of gathering in convivial settings to enjoy a sumptuous feast has persisted throughout the history of humankind. Dating back as far as prehistoric man, the consumption of substantial amounts of food to celebrate the midwinter solstice has been discovered through archaeological finds in locations such as Stonehenge.

In the time of the Romans, the winter festival known as Saturnalia began on the 17th December and involved a week-long celebration of formal ceremony and parties. The household feast could last for several days and even included slaves who were not normally participants of events. Pagan celebrations involving days of feasting, drinking, performances, games and gift giving soon evolved into Christian celebrations with new traditions taking shape through the centuries.

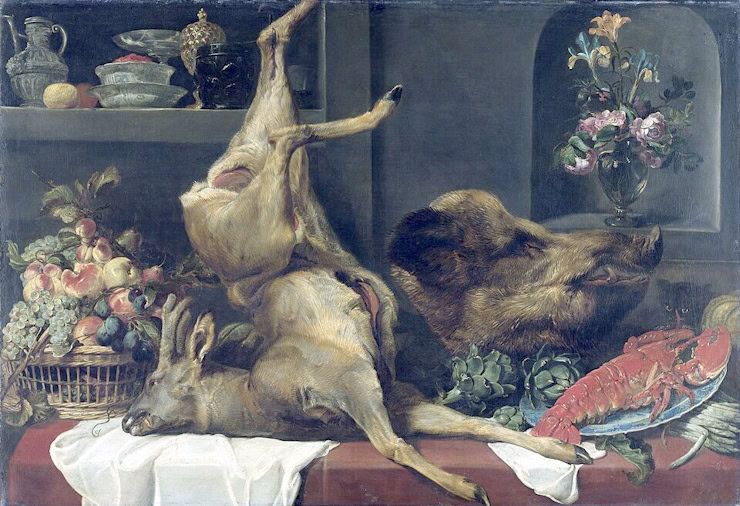

In medieval England, the usual frugality of the year was paused for Christmas celebrations where a sumptuous feast was enjoyed by those who could afford it. The centrepiece however was not turkey as it is today, but instead wild boar.

The monastic community took the celebration of Christmas as an opportunity to embrace a bit of luxury with the inclusion of spices, fish and wine which were usually rationed. In time, this came to include the enjoyment of large cuts of meat such as pork, venison and roast beef.

For the monks of more wealthy monasteries, this indulgence was taken to extremes, with vast amounts of food consumed, as well as wine.

The monasteries also benefited from payments either in the form of money or items which were known as pittances. Examples of pittances included payment of spices for the dinner table or the offer of a goose for the Christmas dinner, as demonstrated by a pittancer’s account taken from the archives of Worcester Cathedral. These offers were rewarded with prayers and ensured that the monastery enjoyed a particularly luxurious feast on the occasion.

Naturally, the extravagance of the meal depended heavily on the wealth of the household, whilst those dining in a fine country home or castle enjoyed a plethora of meat dishes and large portions of food, those from more modest backgrounds made the most of what they had, whether it was meat or fish, sometimes used to make a stew.

One of the more luxury medieval items on the menu included a whole boar’s head which would be filled with a variety of spices to give it more flavour. Moreover, pies with various hearty fillings were an essential feature of the Christmas table.

Bread heavily featured on the menu, including in bread sauce with recipes dating back to the 1400s. This mainstay of the British diet was incorporated into other dishes by both the wealthy and the poor. Sometimes in wealthier homes, the leftover bread and pastry from pies was donated to the poor who waited anxiously at the gates of the manor house, or simply until it was thrown away.

For the upper classes of medieval society, the extravagance of a roasted boar head as a centrepiece and a plethora of enormously rotund and well-filled pies was not only a demonstration of indulgence but also a method of exhibiting wealth and status to guests.

By the Tudor period, the Christmas feast truly came into its own, characterised by the opulence and gluttony of King Henry VIII’s court, feasting in the royal household was a marathon not a sprint. Primarily, meat was star of the show, not one type such as wild boar, but a whole host of wild animals.

Another common sight on the banquet table of a Tudor Christmas was a rotund well-filled pie, often consisting of several birds within a bird. Included in this extensive list of meats, varying from beef, venison to all types of birds, was the introduction of turkey to the menu, which was seen as exotic and most definitely a luxury to be enjoyed by a select few.

The arrival of turkey on the dinner table in 1523 was an expensive addition for most households, however for Henry VIII and the Tudors, there was hardly a meat off-limits and in time turkey would find a way of ousting the highly favoured boar’s head as the showpiece of the Christmas table.

Whilst the Tudor dinner was characterised by gluttony and an endless array of dishes, a century later the English Civil War saw the banning of Christian holidays including the celebration of Christmas. Whilst some traditions were practised in the privacy of one’s home, the Puritans were keen to point out the gluttony of the past and emphasised the need for frugality and reflection.

Fortunately, with the restoration of the monarchy, Charles II reversed such policies and thus the tradition of gathering around the Christmas table was restored.

In the following century, a touch of glamour was added to proceedings with the wealthy Georgians not only consuming vast quantities of food but also hosting ostentatious dinner parties.

At a Georgian dinner table meat was still very much on the menu, particularly beef and venison whilst poultry was seen as a side dish. The roast turkey had also gained popularity for those who could afford it, whilst some other recognisable favourites including plum pudding and mince pies also made the shortlist.

During this time, one familiar and controversial part of the Christmas dinner, the Brussel sprout, made its way to England and proved over the centuries to be a hardy crop, growing well in counties such as Norfolk and Lincolnshire.

Other less familiar foods included brawn, which was essentially a meat jelly made from the head of a calf, as well as turtle soup made from green turtles imported from the West Indies. Such delicacies were first and foremost a demonstration of the wealth and status of the household.

Such elaborate feasts however needed a great deal of preparation, the responsibility of which fell to the kitchen staff who for weeks in advance prepared the filling for the mince pies and the Christmas pudding. Other dishes included the Twelfth Night cake which had remained popular since the medieval period, but which now had more Georgian style with the adornment of elaborate icing and sugar figurines.

The impact of Britain’s overseas expansion saw the introduction of new luxury ingredients, such as sugar which was brought back from the plantations of the West Indies and added to many a Christmas recipe.

The traditional meat-infused savoury mixtures of puddings and mince pies were replaced with sweet additions of spiced fruits, nuts and sugar, transforming Christmas classics such as mince pies into the recognisable flavours of today. King George I was said to have requested a plum pudding to be part of the Christmas feast at the royal household and earned him the sobriquet of the ‘Pudding King’.

For the Georgians, the food on the Christmas dinner table was as much a social statement as the clothes they wore and décor of their homes.

The advent of the Victorian era saw much continuity on the dinner table at Christmas with the wealthy enjoying an array of popular meats such as beef, turkey and venison.

One principal difference between the Georgian and Victorian Christmas was the scale. No longer hosting lavish dinner parties, for the Victorians Christmas began to be seen as a family occasion, far more intimate and modest in size and scale than earlier eras.

Whilst Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert influenced many popular aspects of Christmas festivities such as the Christmas tree and the Christmas card, the dinner itself remained unaltered.

In Victorian England, the Christmas dinner of modern times was beginning to take shape, with meat served with a variety of vegetables, such as potatoes, carrots, sprouts and parsnip. Other familiar sweet treats included Christmas pudding, mince pies, gingerbread and chestnuts, served with brandy and mulled wine.

For the upper classes of the 19th century, the meal often began with a soup, such as Palestine soup which was named after its main ingredient, Jerusalem artichokes. The next dish to be served was fish, followed by more fancy concoctions all of which would lead to the main event, roasted meats.

Whilst the rich were able to indulge in these delicacies, the majority of Victorian England was poor and thus a working-class Christmas feast was highly dependent on the household income.

The Christmas traditions of the Victorian period would prove to have the greatest longevity, as the following century saw many of the same Christmas dinner items. In the 1920s and 1930s, turkey had grown to become one of the most popular meats to be served, although still out of the price range of many families as a turkey cost an average person’s weekly wage. Christmas dinner also began to be commercialised with newspaper and magazine segments dedicated to popular recipes.

The advent of the Second World War and six years of frugality altered some of the more familiar festive rituals. Christmas celebrations were reduced in scale and with many men fighting abroad and children sent to the countryside as evacuees; many families were divided for the first time on Christmas Day.

The scarcity of products and food rationing meant that people were forced to make do with what they had or find substitutes for key ingredients. Despite the hardships and shortage of resources, people still made the effort to celebrate in any way they could.

Post-war Christmas tables in the following decades however were jubilantly restored, and today many Christmas dinners have the same traditional key ingredients such as turkey, potatoes, vegetables, mince pies and pudding.

From the extraordinary feasts of the Tudor period to the lavish dinner parties of the Georgians, the British Christmas dinner has a long and evolving history which continues to be celebrated.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th December 2025