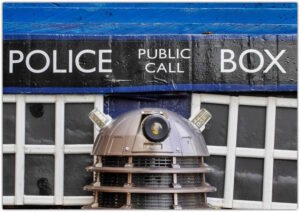

One dark November evening in 1963, an unlikely form of time travel was revealed to the British public. It was heralded by outlandish whoo-ee-oo music supported by a sinister dum-de-dum bass. The time-travelling Doctor Who had arrived on Planet Earth’s TV screens, and his intergalactic machine of choice was, of all things, a common-or-garden police telephone box. Or at least, that’s what it appeared to be. Scary modernist stuff indeed.

Rather than being multi-dimensional interstellar vehicles swooshing through the cosmos, police boxes were sturdy, practical, and familiar items that didn’t go anywhere. They were an important element of the UK’s street furniture from the 1920s onward, as they appeared in their dozens in towns and cities throughout the land.

Outside the Museum of Classic Science Fiction in Allendale. Author Dave Owens. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

Outside the Museum of Classic Science Fiction in Allendale. Author Dave Owens. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

The police box was an essential component in the never-ending war on criminals. In that sense, there were parallels with Doctor Who’s police box Tardis (standing for “Time and Relative Dimension in Space”). Fortunately, police officers did not have to contend with villainous cybermen or metallic-voiced extra-terrestrials wagging a strange proboscis and screeching “Exterminate! Exterminate!” Having said that, police officers might claim that Saturday nights in some of Britain’s cities can present greater challenges and even odder sights.

Police boxes were usually made from cast-iron or wood, although a few brick examples exist, and were large enough to contain a phone, a first aid kit, a heater and other essentials in the fight against crime. They also provided a safe haven for PC 99 and company to take a break and a nice cuppa tea when exhausted by the eternal vigilance of keeping the streets crime-free.

The first examples of police boxes had had been installed in the USA soon after the invention of the telephone. The phones were directly linked to local police stations and could be used by both police and public. Originally, members of the local community were allowed access to the police box via a special key. This would open the police box and then remain firmly in the lock until released by a police officer with a master key, to avoid any misuse.

An 1894 advertisement for the “Glasgow Style Police Signal Box System”, sold by the National Telephone Company

Northern cities in Britain were particularly proactive in following America’s example. Impressive red cast-iron police boxes were erected in Glasgow from 1891, with lighting on top at first powered by gas and then by electricity. The electric lighting was an essential part of the system, as it flashed on and off to show that the local police were calling the box to raise an alert. The realistic flashing light on top of the Tardis as it lands somewhere new in a distant galaxy is just one of the elements that adds to the surreal atmosphere of Doctor Who.

In England, police boxes appeared firstly in Sunderland and then Newcastle-upon-Tyne by 1925. The Glasgow examples had literally been tall upright phone booths. By the 1920s, the potential for the police box to offer more than this was exploited by Chief Constables, led by Frederick J. Crawley, who headed up the forces in both Sunderland and Newcastle at different times. Manchester and Sheffield followed suit with improved multi-purpose versions, while the Metropolitan Police developed their own iconic blue police boxes designed by Gilbert Mackenzie Trench. These were later installed elsewhere in Britain and provided the inspiration for the Tardis. Motoring organisations such as the Automobile Association (AA) and Royal Automobile Club (RAC) also had their own phone box networks.

Blue Police Box

Blue Police Box

In Sheffield, meanwhile, a very distinctive type of police box, painted in fresh green and white, became the standard. At the height of their popularity and use, Sheffield’s crime busters had access to no fewer than 120 boxes of this type, located throughout the city. Now, just one remains, nestling against the stone wall of Sheffield’s Town Hall on Surrey Street.

Sheffield’s green and white boxes were introduced by the city’s Chief Constable, Percy J Sillito, in 1929, making them contemporary with the Trench police boxes. They were now not just phone boxes, but basic street offices where police officers could write their reports. The officers on patrol also had access to the all-important phone, the first aid materials, the heater, and the tea. In emergencies, the police boxes could also be used to lock-up miscreants, though whether they also had access to the tea and phone is unrecorded. Not that the phone would have been much use, of course, unless the desk sergeant at the local police station was in a chatty mood. Doubtless both the officer and his prisoner did not have to wait long for the police van to arrive. The wooden walls of the police box might not have stood up too long against a determined villain.

A 1929 police box on Surrey Street, outside Sheffield Town Hall. It is still used as a post for city ambassadors, providing tourist information.

A 1929 police box on Surrey Street, outside Sheffield Town Hall. It is still used as a post for city ambassadors, providing tourist information.

Time was running out for the police boxes even as they were being made famous by the time- and space-conquering Tardis of Doctor Who. A contemporary BBC television programme, Z-Cars, depicted officers relying on car radios, not police boxes. Police radios had been available since the 1920s in America, but they were not generally available to police officers on the street. The first radios were too bulky and could only be used inside buildings or installed in cars.

In the UK, wireless telegraphy was originally used for communication as it was more secure. When police radio was installed in cars, it advanced the methods and methodology of policing, but there were still plenty of officers working on foot, or “pounding the beat”. Police boxes remained essential forms of communication for them in Britain until the 1960s, when personal radios and increased car use made them redundant. Policing in Britain would never be the same again. Z-Cars marked the start of a new approach to police in the media as well. The programme will also always be famous, for viewers of a certain age, as the series that launched national treasure, the actor Brian Blessed, on the path to celebrity as Police Constable “Fancy” Smith.

As always, a change in technology was welcomes by some, and greeted by others as a sign that the end was in sight. Mutterings and complaints about the loss of “the bobby on the beat” inevitably followed the arrival of those new-fangled radio cars. Nostalgia began to accumulate around the vanishing police boxes, assisted no doubt by the popularity of Doctor Who and his companions conquering the space-time continuum aboard the deceptively spacious Tardis.

Today Sheffield’s remaining green and white police box appears rather charming and nostalgic, rather than an important hub in South Yorkshire’s anti-crime network of the twenty-first century. Yet that is exactly what these police boxes were. It’s easy to forget how radical the whole idea of being able to make contact by telephone was, for some, until the 1960s. Many working-class households did not have access to a telephone until then. Now the green police box is a curiosity, a tourist landmark, and a popular place for taking selfies.

It’s also doubtful that any of the users of the eye-catching green police boxes paused to consider their aesthetics, internally or externally. It’s hard to imagine that the words “You’re nicked, sunshine” would ever be followed by “Never mind, officer, I’ve always wanted to spend time in a delightful police box that looks a bit like a sea front beach hut. Pass me the sonic screwdriver.”

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published 17th April 2023