The famous American Pony Express created the perfect catchphrase for any delivery company: The Mail Must Go Through! The slogan was the inspiration for hundreds, if not thousands of cartoons taking a satirical view of the hazards the Pony Express riders encountered. On the British side of the pond, delivering the mail, whether on horseback in medieval and early modern times, or in horse-drawn coaches in the early nineteenth century, could also be a surprisingly hazardous activity.

The main dangers facing the coaching crews on the UK mail routes were weather and hold-ups, of both the robbery and a more prosaic kind. A wheel might come off, or one of the horses be injured. It was usually not far to the next coaching inn so help could be obtained. Bad weather, especially snow and ice, was always serious, and could result in injury or death to passengers and staff. This was the case for one unlucky mail coach team near Moffat in Scotland. The coachman and guard, unable to get the coach any further in heavy snow, set off riding the coach horses to fulfil their duty and deliver the mail. Both perished in the snow, though the horses survived.

Wild bears, wolves, and big cats having departed from Britain by the nineteenth century, it’s probably fair to say that unlike the Pony Express riders, the coaching staff didn’t expect to find a wolf pack on their trail or a cougar dropping on them from a tree. Yet that was very similar to the experiences of one unfortunate team on the Exeter mail route on the night of Sunday 20th October, 1816.

The coach was the Quicksilver number 209, and it was on its regular route between Devonport and London, calling at various places along the way. It was the last coach to be built by the famous Vidler coach-building company and it was in service for many years. It should have been a routine stop at the Pheasant Inn at Winterslow Hut seven miles from Salisbury on the way to London, and the guard, Joseph Pike, probably wasn’t expecting anything other than an equally routine handover of mail bags.

Suddenly there was an uproar among the horses, and by the light of the lamps, the coachman and guard realised that some large animal was attacking the off lead horse (the horse at the front on the right hand side). The two passengers who had been travelling inside the coach fled into the inn in terror, rushing upstairs and locking themselves into a room to escape the danger. Allegedly, they also locked the main door, so no one else could get to safety!

Outside, the coach was rocking violently as the terrified horses kicked and fought to get away from their assailant. The coaching staff then realised with horror the animal was a lioness! The coachman admitted afterwards he was sure the coach was about to turn over. The guard attempted to shoot the lioness with his blunderbuss. She had the claws of both her front and back legs firmly embedded in the horse’s neck and chest.

The growling of the lioness, the terrified screams of the horses, and general uproar are not hard to imagine. Accounts of the subsequent events were unsurprisingly confusing and even contradictory, but it appears the lioness was quickly distracted by the arrival of a mastiff dog, which attacked her and drew her away from the injured horse. The dog was killed by the lioness about forty yards from the coach. After that she calmed down, sitting growling “in so loud a tone, as to be heard for nearly half a mile”. The dog apparently belonged to the owner of a travelling menagerie, a Mr Ballard, who arrived on the scene with some of his keepers.

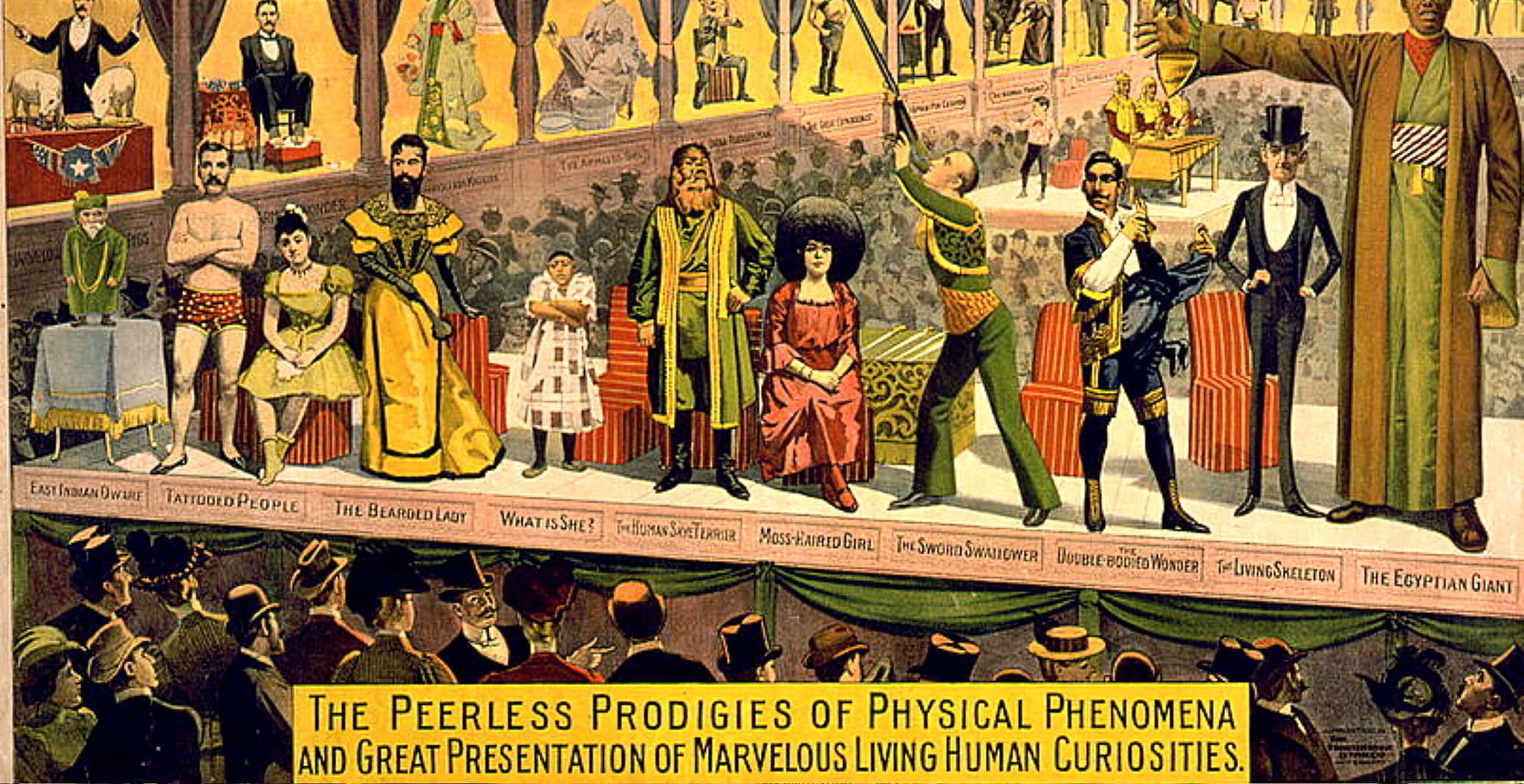

Ballard had started out in show work with a troupe of performing monkeys and dogs known as the Animal Comedians. Circuses and shows were very popular at this time. Many travelling showmen were starting to keep more exotic animals than the dogs and horses that had been involved in the acts in the formative years of circus. Philip Astley, who is often called the father of the modern circus, had been an equestrian performer, and his shows were mainly equestrian events with some dog acts and jugglers and acrobats. Now, travelling showmen were adding more and more exotic animals to their displays.

Lion tamer in cage with two lions, a lioness, and two tigers.

Lion tamer in cage with two lions, a lioness, and two tigers.

The caravans of Ballard’s menagerie were parked up near the inn for the night, so there was no doubt about where the lioness had come from. She headed off towards a barn in a neighbouring farm, with Ballard and his men in hot pursuit. Some accounts say they “enticed” her towards it. She managed to get under the building, where they could hear her growling as loudly as before. They barricaded her in. “Shoot her! Shoot her!” called out the crowd of onlookers who had gathered, and the guard prepared to do just that.

“For God’s sake, don’t kill her! She cost me five hundred pounds, and she will be as quiet as a lamb if not irritated,” responded Ballard.

Somehow they managed to draw her out from under the granary, or crawled in to control her. The lioness was bound up so that she could not harm anyone. In this state they carried her back to the menagerie. It turned out that they had realised she had escaped, and were on her trail, but hadn’t caught up with her until it was too late. Too late for the mastiff dog too, which had presumably been following her scent.

It may not have been the only time one of Ballard’s exotic animals caused a serious incident. In 1810, a leopard had escaped from a menagerie travelling along Piccadilly on the way to Bartholomew Fair. The horses drawing one of the menagerie waggons were frightened, the waggon overturned, and two monkeys and the leopard escaped. The leopard was recaptured, but a keeper was severely injured in the process. While it is not known for certain whether this was Ballard’s menagerie, he certainly had leopards and monkeys among his exhibits.

Ballard’s lioness survived to become a media sensation. No doubt she would be the most popular exhibit at Salisbury Fair, which is where the menagerie was headed. The unfortunate horse she attacked was not as lucky. Its injuries were so bad that it had to be put down. The coach driver was so enraged by the loss that once a replacement horse had been found, he drove the coach up to the caravans, threatening to knife the lioness to death in retaliation. His guard pointed out that he was just as likely to end up dead himself in any encounter with the animal. However, Mark Broadbent of Fenix Carriages, who restored the Quicksilver coach, contends that the injured horse, which was called Pomegranate, did survive.

This extraordinary delay had cost the mail coach just 45 minutes off their regular time, a point that was made to show the dedication of the Royal Mail. The Quicksilver coach, with its smart red and black livery and golden GR (George Rex) became a popular subject for paintings and Christmas cards. In 2015, it went up for sale, still sporting its original paintwork. After this it underwent a two-year restoration project before being shown to the public. The Quicksilver coach is a reminder of the time when the mail had to get through, even when attacked by a lioness.

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published 16th July 2023