Called the “Angel of Prisons”, Elizabeth Fry was a woman of the nineteenth century who campaigned for prison reform and social change with a rigour that inspired future generations to continue her good work.

Artists Suffrage League banner celebrating the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, 1907

Born on 21st May 1780 into a prominent Quaker family from Norwich, her father John Gurney worked as a banker, whilst her mother Catherine was a member of the Barclay family, the family who founded Barclays Bank.

The Gurney family were extremely prominent in the region and responsible for much development in Norwich. Such was the family’s affluence that in 1875, it was personified in popular culture by Gilbert and Sullivan with a quote from “Trial by Jury”, that, “at length I became as rich as the Gurneys”.

Unsurprisingly, young Elizabeth had a charmed life growing up in Earlham Hall with her brothers and sisters.

For Elizabeth, her calling to Christ was evident from an early age and her strength of faith was later harnessed to enact social reform.

Inspired by the preaching of the American Quaker William Savery and others like him, in her early adulthood Elizabeth rededicated herself to Christ and was on a mission to make a difference.

By the tender age of twenty, her own personal life was soon blossoming as she met her future husband, Joseph Fry, also a banker and cousin of the famous Fry family from Bristol. Well-known for their confectionary business, they too, like the Gurney family were Quakers and often involved themselves in philanthropic causes.

On 19th August 1800, the young couple married and moved to St Mildred’s Court in London where they would go on to have a prolific family of eleven children; five sons and six daughters.

Despite her now full-time role as wife and mother, Elizabeth found time to donate clothes to the homeless as well as to serve as a minister for the Religious Society of Friends.

The real turning point in her life came in 1813 after a family friend called Stephen Grellet prompted her to visit Newgate Prison.

Newgate Prison

Upon her visit she was horrified by the conditions she discovered; unable to stop thinking about the prisoners, she returned the following day with provisions.

Some of the harsh conditions Elizabeth would have witnessed included immense overcrowding, with women who were incarcerated forced to take their children with them into these dangerous and distressing living conditions.

The space was cramped with confined areas to eat, wash, sleep and defecate in; the harsh reality of the prison world would have been a startling sight for Elizabeth.

With the prisons full to capacity, many were still awaiting trial and a variety of people with extremely varying convictions were held together. Some of the stark differences would have included those women accused of stealing from the market, alongside someone serving time for murder.

The conditions were grim and without assistance from the outside world, either from charities or their own families, many of these women faced a desperate choice of starving, begging or dying.

These harrowing images stayed with Elizabeth and unable to erase them from her mind she returned the very next day with clothing and food for some of the women she had visited.

Sadly, due to personal circumstances Elizabeth was unable to continue some of her work because of financial difficulties incurred by her husband’s family bank during the financial panic of 1812.

Thankfully by 1816 Elizabeth was able to resume her charity work and focused on Newgate Women’s Prison, by providing the funds for a school within the prison to educate the children who were living inside with their mothers.

As part of a broader programme of reform, she started the Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners of Newgate, which included providing practical assistance as well as religious guidance and assisting the inmates in discovering routes to employment and self-improvement.

Elizabeth Fry had a very different understanding as to the function of a prison compared to many of her peers at the time. Punishment in the nineteenth century was first and foremost and a rigorous system was the only method for wayward individuals. Meanwhile, Fry believed that the system could change, encourage reform and provide a stronger framework, all of which she endeavoured to do through lobbying with parliament, campaigning and charity work.

Some of the more specific requirements she concerned herself with after her numerous visits to the prison included, ensuring men and women would be separated, with female guards provided for the female inmates. Moreover, after witnessing so many individuals serving time for such a broad spectrum of crimes, she also campaigned for housing of criminals to be based on the specific crime.

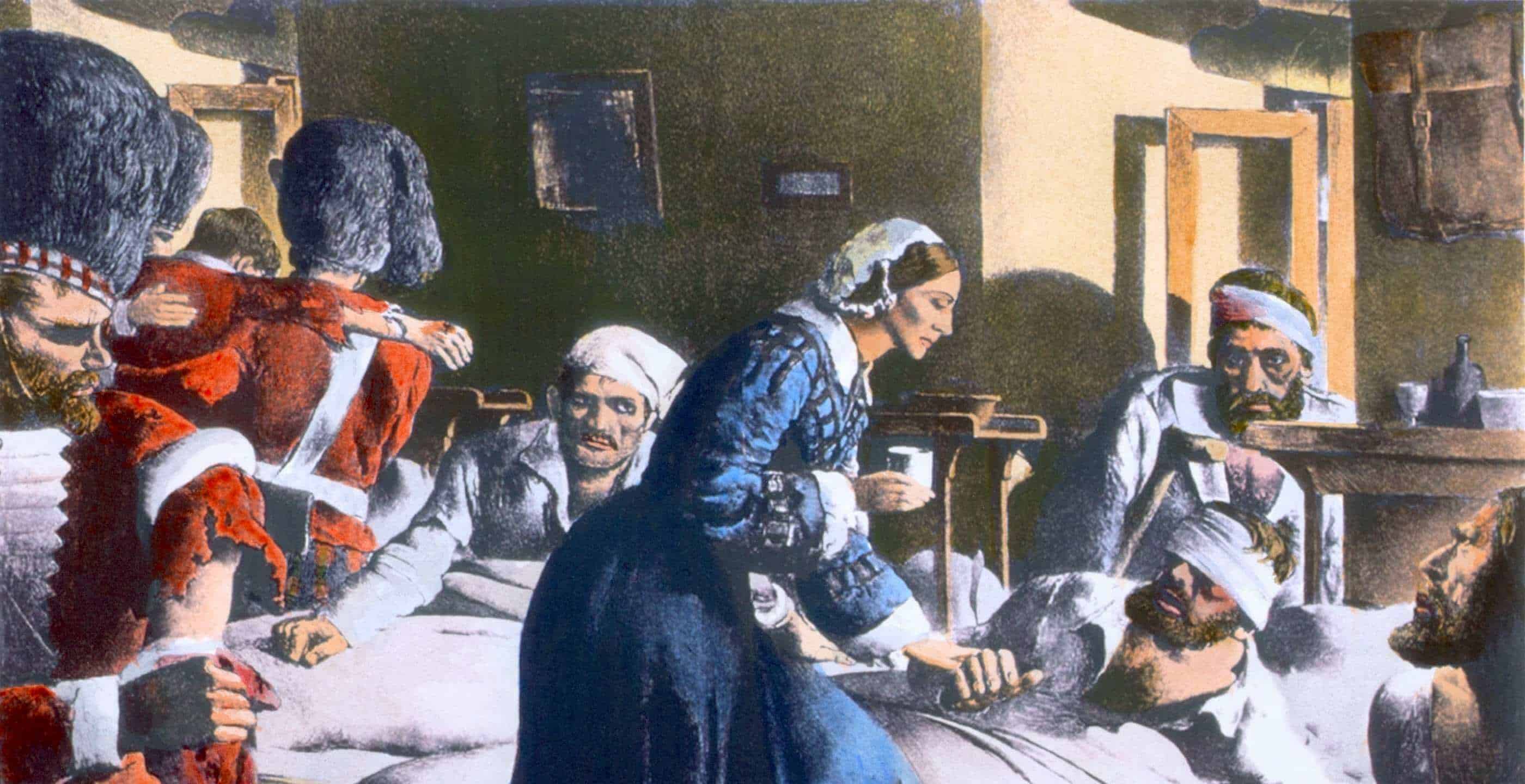

She focused her efforts on encouraging the women to gain new skills which could help better their prospects upon leaving prison.

Elizabeth Gurney Fry reading to prisoners in Newgate Prison. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Elizabeth Gurney Fry reading to prisoners in Newgate Prison. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

She gave practical advice in hygiene matters, religious instruction from the Bible, taught them needlework and gave comfort in some of their most difficult moments.

Whilst some individuals warned Fry of the perils she may incur when visiting such dens of iniquity, she took the experience in her stride.

Elizabeth Fry’s concern for the prisoners’ welfare and experiences within the confines of the prison wall, also extended to the circumstances of their transportation which often included being paraded through the streets in a cart and being pelted by the people of the town.

In order to stop such a spectacle, Elizabeth campaigned for more decent transportation such as covered carts and visited around one hundred transport ships. Her work would eventually lead to the formal abolition of transportation in 1837.

She remained determined to witness tangible change in the structure and organisation of the prisons. So much so, that in her published book, “Prisons in Scotland and the North of England”, she gave details of her nightly visits in such facilities.

She even invited titled individuals to come and see the conditions for themselves, including, in 1842 Frederick William IV of Prussia, who met with Fry in Newgate Prison on an official visit which greatly impressed him.

Moreover, Elizabeth benefited from the support of Queen Victoria herself, who admired her efforts in improving the lives and conditions of those most in need.

In doing so, her work helped to increase public awareness as well as the garnering the attention of the lawmakers in the House of Commons. In particular, Thomas Fowell Buxton, Elizabeth’s brother-in-law who also served as MP for Weymouth proved instrumental in promoting her work.

In 1818 she also became the first woman to provide evidence to a House of Commons committee on the subject of prison conditions, ultimately leading to the Prison Reform Act of 1823.

Her campaigning helped to change attitudes as her unorthodox approach began to yield positive results, leading some to believe that her rhetoric of rehabilitation could be more effective.

She chose to promote her ideas across the English Channel in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany.

Whilst she encouraged prison reform, her humanitarian efforts continued elsewhere, as she sought to tackle a variety social issues.

She helped to improve the lives of the homeless by setting up a shelter in London and opening up soup kitchens after seeing the dead body of a young child who did not survive the brutal winter night.

Her attention extended specifically to helping women, particularly fallen women, by providing them with accommodation and opportunities to find other sources of employment.

Elizabeth’s desire for better overall conditions in different institutions also included proposed reforms in mental asylums.

Her focus was widespread, tackling social issues which had previously been taboo topics. Alongside her fellow Quakers, she also supported and worked with those who were campaigning for the abolition of slavery.

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale

By the 1840’s, she had founded a nursing school in order to improve the education and nursing standards of those in training, serving to inspire Florence Nightingale who worked alongside fellow nurses to help the soldiers of the Crimean War.

Elizabeth Fry’s work was outstanding, ground-breaking and inspiring for a new generation who wanted to continue her good work.

In October 1845 she passed away, with more than a thousand people attending her memorial, her legacy was later to be recognised when she was depicted on the five pound bank note in the early 2000’s.

Elizabeth Fry was a woman born into a prominent family with wealth and luxury, who chose to use her position to better the lives of others, drawing attention to the social tragedies across the country and raising a social conscience in the public which had been somewhat lacking.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 23rd November 2021