In 1826, Londoners were avidly discussing the latest entertainment from the talented Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), who would later become known as the inventor of the Daguerrotype, the earliest commercial form of photography.

The presentation that everyone was talking about included the stunning “L’Abbaye de Roslyn, effet de soleil”. It had been drawing the crowds in Paris for two years. Now it was finally on show at the Regent’s Park Diorama, a specially constructed building designed by architect Augustus Charles Pugin, father of the better known Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin.

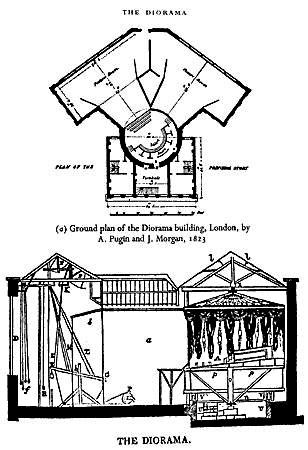

Ground plan of Louis Daguerre’s Diorama in London

Ground plan of Louis Daguerre’s Diorama in London

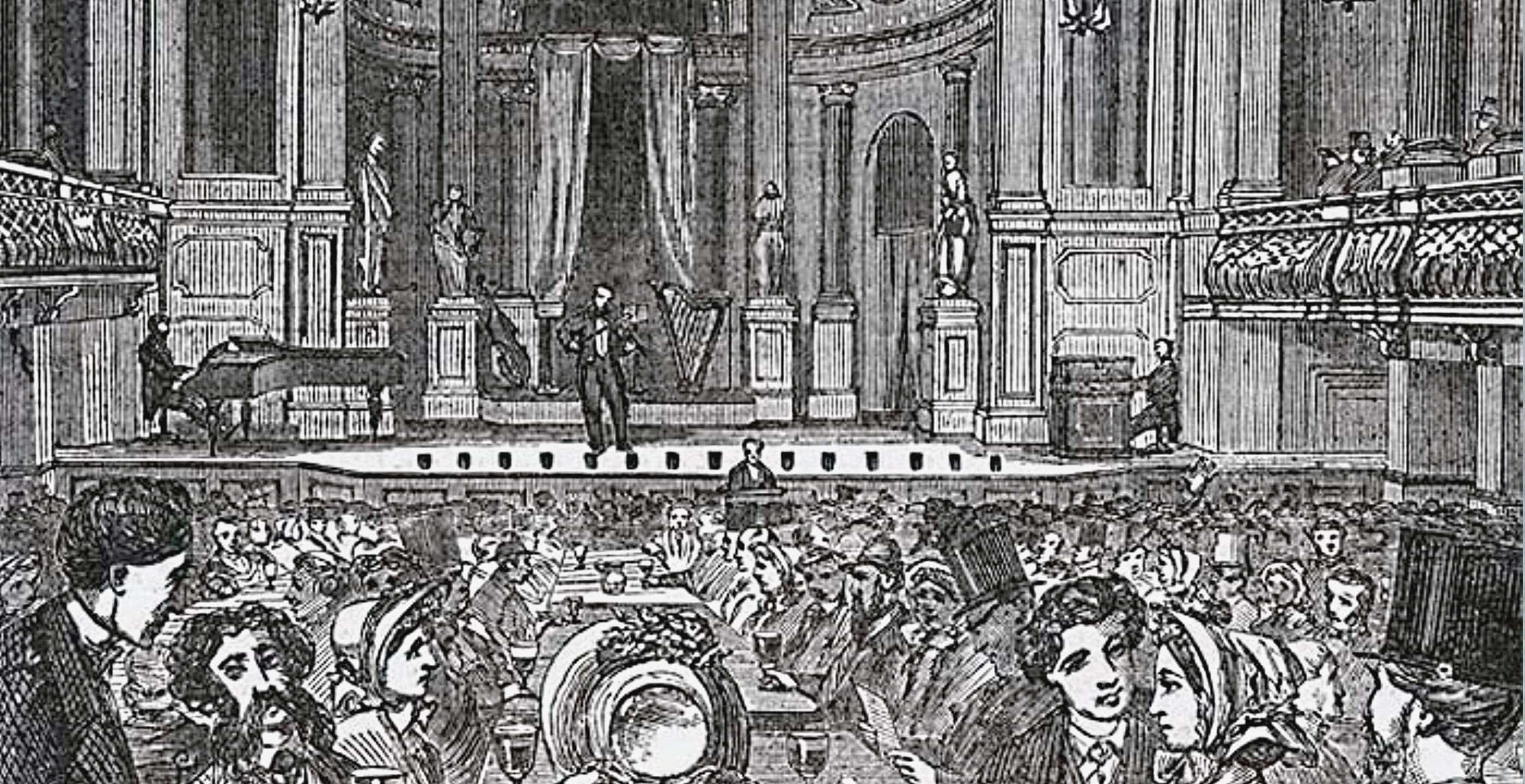

The prime of London’s fashionable society settled itself into the elegant viewing area, which slowly revolved past massive landscapes up to 22 metres long and 14 metres high (72 feet x 46 feet). As the audience watched, the interior of Rosslyn Chapel in Midlothian was revealed, with trees visible through the windows “sparkling when the sun bursts out upon them…absolutely magical,” as one person wrote in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. The effect was augmented by the sound of Scottish airs played on the bagpipes.

Daguerre had hit on a winning formula. His own expertise lay in designing and painting stage sets, as well as lighting them with supreme skill. Combining his talents with the rage for the romantic and Gothic, as exemplified by the literary work of Sir Walter Scott, Daguerre brought the lonely chapel of Rosslyn, with its hints of mystery and the supernatural, right into the heart of Georgian London.

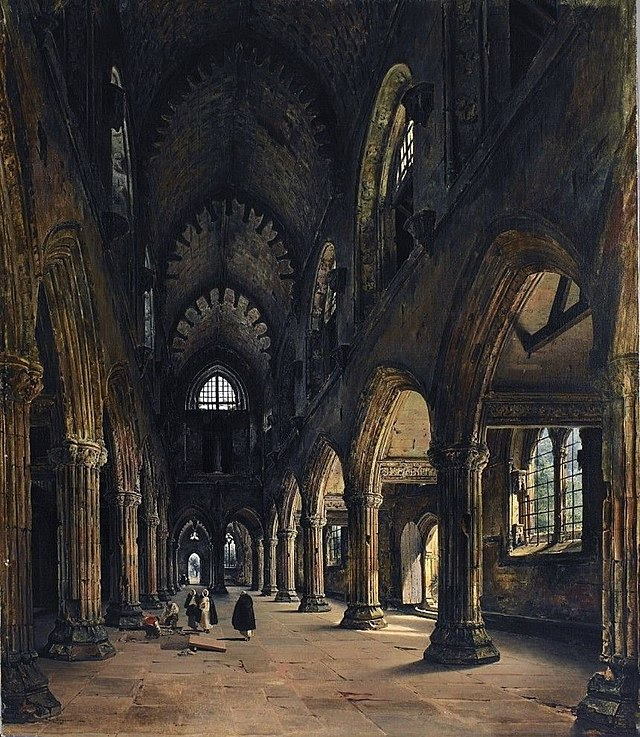

Daguerre, Interior of Rosslyn Chapel, oil on canvas, 1824

It must have seemed the embodiment of Scott’s romantic (and imaginative) work “The Lay of the Last Minstrel”, which references Rosslyn Chapel:

The reviewers were ecstatic. “It surpasses every representation of an architectural structure we ever saw…”; “persons who have seen the chapel…might think themselves transported by some magic spell to the scene itself – so perfect is the illusion”. It was reported in The Times that: “…we consider this view to be decidedly the best that has yet been exhibited, and so good, that for excellence of painting, for force of illusion, we cannot believe it will be possible to surpass it.”

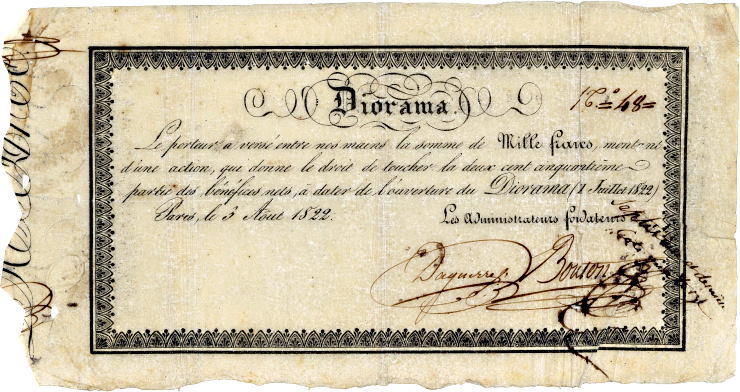

Diorama was the outcome of a partnership formed in 1821 between Daguerre (1787-1851), and artist Charles Bouton (1781-1853), who opened the first Diorama in Paris in 1822. Essentially, the Diorama was a supremely effective 3-D illusion, created by painting on giant pieces of partly translucent material. These were set in multiple layers in a long box-shaped building, not unlike an early box-camera.

Through clever effects of lighting, mainly natural sunlight but also artificial sources, the viewers saw magical effects of sunrise, moonlight, rainbows and dramatic weather revealed before their eyes.

The Regent’s Park Diorama opened just a year after the Paris building went into operation. Daguerre was married to an Englishwoman whose family name was Smith or Arrowsmith, and it seems likely that the British Patent application made by a John Arrowsmith in 1824 was from a family member. By this time, the Diorama in Regent’s Park was already in operation.

A Diorama came into existence in Edinburgh so quickly afterwards that it seems certain it was not an “official” Daguerre-Bouton Diorama. It has been suggested that some of the paintings for this enterprise were by the talented Scottish artist David Roberts, who went on to make a name for himself through his Orientalist paintings. The management of the Edinburgh venture, spotting a good thing when they saw it, kept some of the themes chosen by Daguerre and Bouton such as “Trinity Chapel in Canterbury Cathedral”. Bristol, too, saw a very early “Diorama” show, again with similar themes.

Objections were raised due to the Patent, but these were largely ignored by the local authorities: “The Foreign Artists who introduced the Diorama… would restrain the talents of our native artists, under the ridiculous pretence of copying their pictures”.

Official Daguerre-Bouton Dioramas soon opened in Liverpool, Manchester, Dublin and Edinburgh. Smaller versions opened too, including one in Oxford Street. The booklet accompanying the Liverpool venture had stated that “Not less than £15,000 were expended before the two pictures above mentioned were displayed”, giving some idea of both the investment required for the expansion plans and also the potential the investors believed the Dioramas could offer.

Stock certificate of the Société d’exploitation du Diorama de Paris for 1000 Francs, issued on 3 August 1822, signed in the original by the two inventors and directors Charles Bouton and Louis Daguerre. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Stock certificate of the Société d’exploitation du Diorama de Paris for 1000 Francs, issued on 3 August 1822, signed in the original by the two inventors and directors Charles Bouton and Louis Daguerre. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

They were overoptimistic, it appears. Daguerre eventually bankrupted himself and the Diorama phenomenon was effectively over by 1839, when the original Paris building burned to the ground. The Edinburgh venue closed the same year. Bouton attempted a new venture in Paris in 1843.

The Diorama undoubtedly set new standards in entertainment, yet it was also a development from exhibitions of giant panoramic scenes that had amazed exhibition-goers earlier in the century. Part of the success came from the picturesque landscapes and Gothic scenes chosen as subjects. A surviving painting by Daguerre of the interior of Rosslyn Chapel gives some idea of how stunning the effects must have been, and also of how creatively he manipulated the scene to impress the audience.

In his painting, the broad pillars of the chapel stretch up and up, overwhelming the tiny figures at their base in a way that is not at all representative of the real interior of Rosslyn. This perspective was nonetheless copied by many artists that came after him, giving the impression of a mighty cathedral. Watching the light change on similar images 14 metres high, with a mass of detail to observe right in front of the eye, must have been an awe-inspiring entertainment.

The journal “The Mirror of Literature” wrote of the Rosslyn Diorama, which was shown in conjunction with a picture of “The Ruins of Holvrood Chapel, Edinburgh, by Moonlight”: “The magic of this effect of light is indeed most extraordinary and the illusion is complete and enchanting…”

Daguerre, Ruins of Holyrood Chapel, c. 1824

Daguerre, Ruins of Holyrood Chapel, c. 1824

The Diorama helped to reinforce the vision of the “picturesque landscape” or “romantic ruin” that would continue to inspire art, literature and architectural forms as the century progressed. It would also influence photography and cinematography as they developed, so although the period of its popularity was relatively brief, Diorama is still influential today.

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published 24th March 2023