Often referred to as the Romance languages, the mainly French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian spoken words derive from the time of Roman occupation and the Latin language that united the empire. This was further reinforced as the Roman Catholic faith spread throughout southern Europe.

Even the days of the week of these languages have romantic connotations, deriving their names from the heavens above. Monday is named after the moon in French – lundi (la lune is ‘the moon’), mardi (Tuesday) is named after the planet Mars, mercredi (Wednesday) takes its name from the Roman god Mercury, whilst jeudi (Thursday) is named after Jupiter, vendredi (Friday) is based on the Roman goddess Venus, with samedi (Saturday), or “Saturn’s Day” and finally, most of the Romance languages have adopted the Latin for “Lords Day”, as in the French dimanche.

However southern Britain, or England as we now refer to it, was left in somewhat of a vacuum from the rest of Europe, when the occupying Romans quickly decamped from the region in circa 410, leaving the natives to fend for themselves against the ravages of the invading Anglo-Saxons tribes.

The Anglo-Saxon tribes that arrived were a pagan lot who worshipped many gods, with each god controlling a particular part of their everyday life, including the family, the growing of the crops, the weather, and in particular, war and death!

And so it remains to this day, that in stark contrast with those Romance languages, the Anglo-Saxon English speaking world share the common legacy that their days of the week still herald the cries of those pagan warrior tribes. The days of the week that we all recognise today are indeed named after the mainly Anglo-Saxon gods that controlled everyday life, for example;

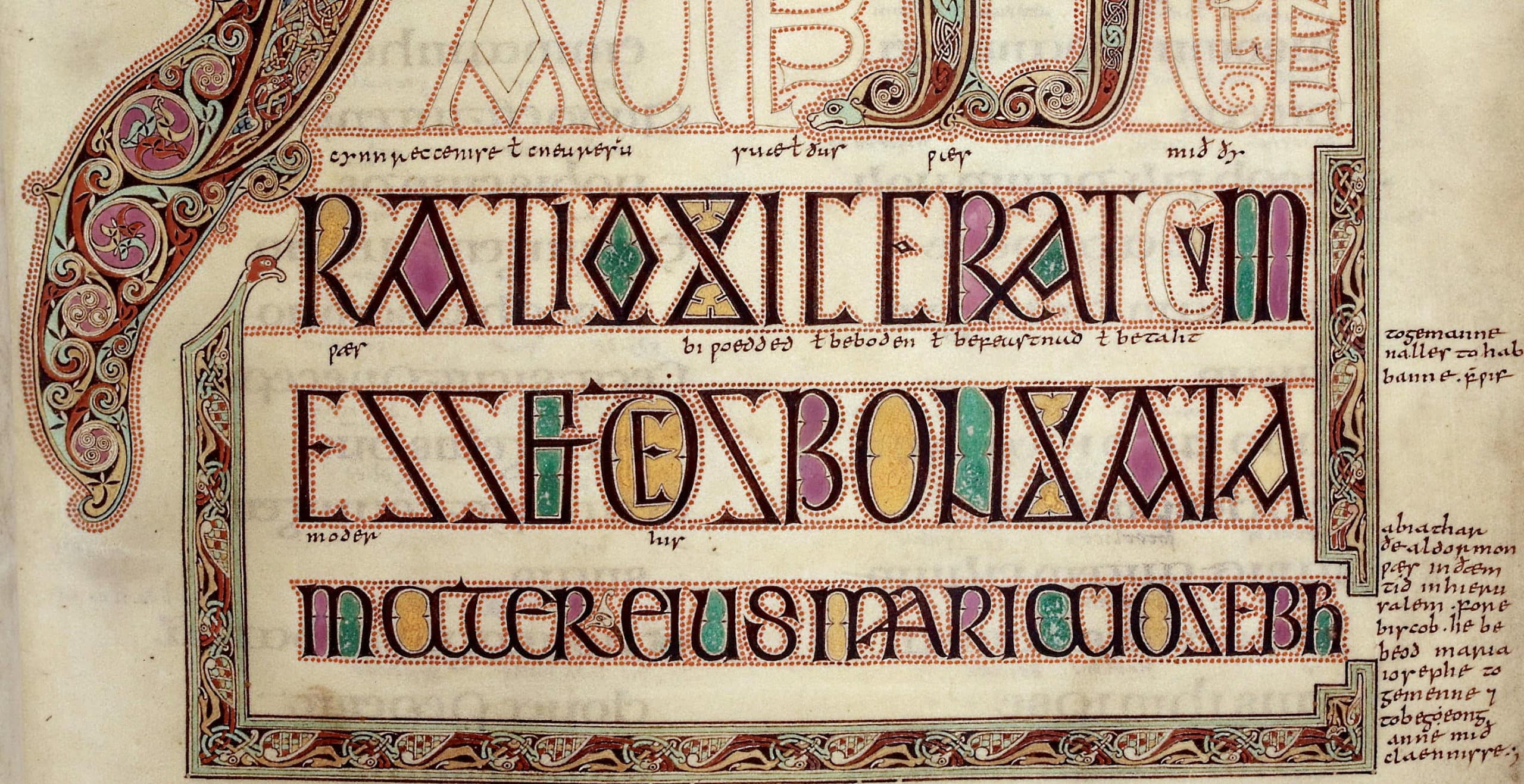

Monday – Monandæg (Moon’s day – the day of the moon, in Old Norse Máni, Mani “Moon”, please see below);

Tuesday – Tiwesdæg (Tiw’s-day – the day of the god of war and combat. Tiw, Tiu or the Norse Tyr, was also known as the sky god and was recognised as the most skilled in swordplay… despite having only one hand! He was also famed for his honour, justice and courage);

Wednesday – Wodnesdæg (Woden’s day – the day of the chief Anglo-Saxon god Woden (Norse Odin). Also associated with war, Anglo-Saxon warriors would look to him to protect them on the battlefield. In particular they believed he could guide their spear arms, as the spear was Woden’s sacred weapon);

Thor crashes through the heavens wielding the lightning-sparking hammer Mjöllnir, the gloves Járngreipr, and the belt Megingjörð. His chariot is pulled by the goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. By Johannes Gehrts, 1901.

Thor crashes through the heavens wielding the lightning-sparking hammer Mjöllnir, the gloves Járngreipr, and the belt Megingjörð. His chariot is pulled by the goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. By Johannes Gehrts, 1901.

Thursday – Ðunresdæg (Thor’s Day – the day of the god Ðunor or Thunor. One of the most famous gods in Norse mythology, Thor is widely recognised as the hammer-wielding god associated with thunder, lightning and fertility. His hammer shaped amulets have been found in many an Anglo-Saxon grave);

Friday – Frigedæg (Frige’s day – the day of the goddess Frige (Norse Frigg), wife to Woden. Woden’s wife was the goddess of love and was associated with all things to do with home, marriage and children. Recognised as the mother of the earth, the Anglo-Saxons would look to her to provide a good harvest);

Saturday – Sæternesdæg (Saturn’s day – the day of the Roman god Saturn, whose festival “Saturnalia,” with its exchange of gifts, has been incorporated into our celebration of Christmas. Unlike other English day names, no god substitution seems to have been attempted here);

Sunday – Sunnandæg (Sun’s day – the day of the sun, in Old Norse Sól, Sol “Sun”, see below).

‘The Wolves Pursuing Sol and Mani’ (1909) by J. C. Dollman.

‘The Wolves Pursuing Sol and Mani’ (1909) by J. C. Dollman.

In Norse mythology Sol and Mani were sister and brother, who first emerged when the world was forming. After the gods had created the sky, Sol drove her Sun chariot through the sky to light up the earth. Mani’s chariot guided the course of the Moon, controlling its waxing and waning. Both chariots are depicted travelling at great speed through the skies pursued by wolves. It was believed that if the wolves caught up with the Sun and Moon, the stars would all disappear from the sky and it would signal the final battle between good and evil that could see the end of the world.

And just one final thought… Easter is obviously a Christian celebration, yes? No, the word Easter comes from the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring and the dawn, Eostre, or Ostara, or Eéstre. According to the Venerable Bede, during Eostremonath (the old Anglo-Saxon name for April), folk would hold festivals in her honour to welcome the first warm spring winds.