During the Industrial Revolution, the working classes of northern England flocked to work in coal mines, pits and cotton mills to make a living. Not the most likely place for the birth of a traditional pastime? Well actually, yes. It was among these cobbled streets that the English tradition of clog dancing was born.

Although the clog dancing of northern England that we recognise today was started here, it was long before this that dancing in clogs began. It is thought that ‘clogging’ came to England as early as the 1400s. It was at this time that the original completely wooden clogs altered and became leather shoes with wooden soles. In the 1500s, they changed again, and separate wooden pieces were used to make the heel and toe. This early dancing was less complicated than the later ‘clog dancing’.

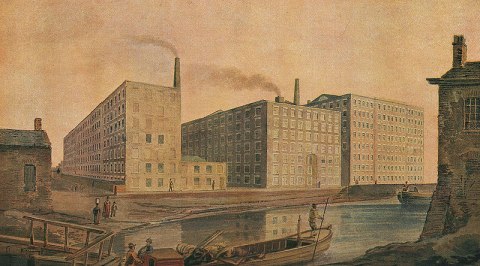

Clog dancing is most notably associated with the 19th century Lancashire cotton mills, with towns like Colne. It is here that the term ‘heel and toe’ was first used, derived from the changes made to the clog in the 1500s. Coal miners in Northumbria and Durham developed the dance too.

The clog was a comfortable and cheap form of footwear, with alder soles, ideal for these industrial workers in the Victorian period. It was especially important to have this hardwearing footwear in the cotton mills, because the floors would be damp, to create a humid environment for the spinning process.

Initially, the dancing was started simply to alleviate boredom and warm up in the cold industrial towns. It tended to be men that would dance and, later, as its popularity grew to its peak between 1880 and 1904, they would compete professionally in music halls. The money awarded to winners would be a valuable source of income for the poor working classes. There was even a World Clog Dancing Championships, which Dan Leno won in 1883.

Women also participated, though, and later their dancing, too, became popular in music halls. They would also dress up colourfully and dance in the villages, carrying sticks to represent the bobbins in the cotton mills. Dancing clogs (night /‘neet’ clogs) were made from ash wood, and were lighter than those worn to work. They were also more ornate and brightly coloured. Some performers would even nail metal to the soles so that when the shoes were struck, sparks would fly!

Other entertaining performers at the time were the canal boat dancers. Along the Leeds and Liverpool canal, these men would keep time with the sounds of the bolinder engine. They would compete with the clog dancing miners in the pubs lining the canals, and frequently win. Onlookers would also be impressed by their table-top dancing, managing to keep the ale in the glasses!

Clog dancing involves heavy steps which keep time (clog is Gaelic for ‘time’), and striking one shoe with the other, creating rhythms and sounds to imitate those made by the milling machinery. During competitions, judges would sit either beneath the stage or behind a screen, allowing them to mark performances purely on the sounds made. Only the legs and feet move, the arms and torso remaining still, rather similar to Irish step dancing.

There were various styles of clog dancing, like Lancashire-Irish, which was influenced by the Irish workers that migrated into the mills of Lancashire. The Lancashire style also tended to make more use of the toe in the dance, whereas Durham dancers used more heel. Other styles included the Lancashire and Liverpool hornpipes. Early clog dances did not include ‘shuffles’, but the later clog hornpipe, influenced by the hornpipe stage dance of the 18th century, did include these steps. In 1880 clog hornpipes were being performed on city stages all over England. Clog dancing could be performed alone or in a dance troupe, such as the Seven Lancashire Lads, which the legendary Charlie Chaplin joined in 1896.

As the twentieth century dawned, clog dancing in the music halls declined. Its association with the lower classes and undesirable aspects of society, like betting, became more apparent, particularly in contrast to the more refined theatre experience. It was also being replaced by the more dazzling tap dancing, which had developed in America at the end of the 19th century. It was a mixture of clog, Irish step and African dance. There was, however, renewed interest in folk dancing after World War II, leading to steps being revised and taught again.

Today, although clog dancing is certainly not as popular as it was in the 1800s, clog makers still exist and performances can often be seen at folk festivals like Whitby. Skipton, north Yorkshire, also hosts a festival of English step dance every July, helping to keep the tradition alive.