They seem to be everywhere one looks.

One of Britain’s best loved animals: the cat.

They’re spotted on a bench in the sunshine. Perched on a country wall. Climbing trees in the back garden. Grooming themselves on the sofa. Scratching nosey dogs. They’re even on social media, with hundreds of thousands of ‘chonks’ and ‘toe beans’ to be seen and adored. Smoothie, Tussetroll and Tingeling. Balam, Thurston Waffles and Wilfrid. Maple, Lotus and Smudge. These are household names in the social media cat world.

These creatures come in many colours from white to black, orange to grey, spotted to striped. Long haired, short haired, or no hair. We pet them and brush them, feed them and clean their litter pan. We sigh – or shout – when they sharpen their claws on furniture or the carpet. In exchange for our tolerance they emit that wonderful, calming sound we’re blessed to hear: the purr.

There’s nothing better than enjoying a mystery novel whilst having one of these furry creatures curled up next to you on the sofa or your lap. We can all attest to the disdain we feel towards them when we settle down in bed for the night, only to hear that familiar scratch-scratch-scratch at the bedroom door.

We haul ourselves up and head to the door to let the little bright eyed felines (or should I say demons?) inside the room. They jump onto the bed and curl up next to us or hide away under the bed for the night. There’s nothing quite like that feeling of a little prickly tongue or an insistent meow waking you up, pleading for the morning meal. Or we are rudely awakened by a distant crash or clatter.

Britain’s love for cats hasn’t been like this forever though.

A Roman mosaic featuring our feline friend

A Roman mosaic featuring our feline friend

The Beginnings

Cats were brought to the British Isles by the Romans, a millennium ago. When the Roman Empire fell, the Romans left but many of their cats remained and have inhabited the British Isles ever since. The Vikings, who were next to raid, even brought some of the furry little creatures back home with them.

Little Evils

During the Middle Ages, when there were witch hunts, cats were seen as familiars, or witches helpers. This resulted in many innocent cats being killed or sacrificed in the hopes of ridding evilness. Black cats in particular were suspected of being affiliated with witches. This lowered the cat population immensely.

However, strangely enough, black cats have been considered a symbol of good luck in the UK in more recent years, but unlucky symbols in the US and on the Continent. During the British Industrial Revolution, if a black cat embarked on a ship it was a good luck omen. Likewise, a woman was advised to give her sailing husband a black cat for luck. White cats, on the other hand are considered unlucky in the UK, as their white coat resembles that of a ghost. Ironically, white cats in many countries, particularly in Asia and the Near East, are considered lucky.

The Plague or ‘Black Death’

Whilst new evidence is said to point not to rats and mice as carriers of the so called ‘Black Death‘ virus, but to lice on humans and fleas on animals, the declining cat population in the Middle Ages has also been suggested as one reason that plague-carrying vermin were able to flourish. It is speculation of course, but declining cat numbers did occur in Britain during the plague’s peak in the 1300s and 1600s.

World War Two

In 1939, when the Nazis were invading the Continent, Britain’s populace was preparing for the worst. It was believed that with the dangers of importing goods from abroad, their native food source would eventually dry up as the war went on. The country only had so much arable land and a small seasonal window.

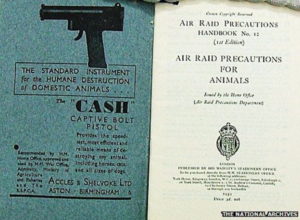

This would not only mean food would be scarce for the populace, but it would mean cats (as well as other pets and livestock) would starve. This would be cruel to the animals and upsetting to pet owners, so one option was to limit the mouths to be fed before the trouble began. With the exception of horses and dogs who were recruited for war work, many other animals were culled as humanely as possible by vets.

Advice to animal owners, 1939, National Archives. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Advice to animal owners, 1939, National Archives. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Moreover, there was a committee formed by the Home Office called the National Air Raids Precaution Animals Committee. This committee was established to provide guidance to civilians on what to do with their animals (domestic, farm, and working) during air raids. The committee members had logos on their vehicles and were given badges and armbands to wear as a means of identification. The organisation was given power by the Home Office to drive around during raids to assist civilians with their animals.

Civilians were given identification collars so in the event of animal-human separation they could, at war’s end, be reunited once more. The committee members could also take animals away to care for them if their owners could not or had abandoned them. This was sponsored by organisations such as the RSPCA and Battersea Cats and Dogs Shelter initially, but within two years of the start of the war they had to cease sponsorship due to financial reasons.

Winston Churchill greets Blackie, ship’s cat of HMS Prince of Wales, 1941

Winston Churchill greets Blackie, ship’s cat of HMS Prince of Wales, 1941

Official Duties

From World War Two onwards, cats were employed by the state as ‘Chief Mousers’ to eradicate vermin in official buildings. In exchange for their services in keeping buildings free from mice and rats, they were given food and board. Over the years, their duties have expanded to welcoming foreign dignitaries and helping to keep the atmosphere of officialdom cordial and sometimes even warm and fuzzy (or should I venture fluffy?). At the end of their term of service they usually retire to the home of an official staff member. Two of the most recent employees of this occupation, Palmerston (stationed in the Foreign and Commonwealth office) and Larry (of Number Ten Downing Street) have had what you might call a hair-raising time, with Larry even having his own Twitter/X account!

Jade is a Canadian, cat mom and freelance writer. She’s also a history graduate and Anglophile, who enjoys a good British mystery novel or period drama.