A time traveller visiting London in the sixteenth century asking for directions to Bartholomew Fair might have received a bemused look from a local. Then it would dawn.

“Ah, sir, you want the way to Bartlemy Fair. Follow me … “

Hey, now the fair’s a filling!

O for a tune to startle

The birds o’ the booths here billing

Yearly with old St Bartle!

The drunkards they are wading,

The punks and chapmen trading,

Who’d see the fair without his lading?

Bartholomew Fair was established by charter of Henry I in 1133. The king granted it to a monk called Rahere who had previously been in service as Henry’s jester. The fair was to raise funds for the Priory of St Bartholomew founded by Rahere in 1123 after his spiritual awakening. St Bartholomew had visited Rahere in a vision and ordered him to build a priory in West Smithfield. All in all, Rahere (and St Bartholomew) can be credited with leaving a great legacy to London: a fair where visitors could overindulge and get into fights, a hospital to patch them up, and the Priory of St Bartholomew to pray for their souls.

The fair was next to Smithfield Market, which held a separate charter granted to the City of London. Drovers and dealers came from all over the country to Smithfield, bringing horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs to sell. The fair of St Bartholmew (an alternative spelling for Bartholomew used by some authors of the period) had a variety of goods and services on offer for visitors and locals. Some fairgoers preferred to pick a few purses (as well as fights) along the way. Indeed, picking a fight was a great way to provide cover for cutting a purse, and both these activities were good ways to end up in St Bartholomew’s Hospital or even on the gallows in the vicinity. While the priory is long gone, just one of the casualties of Henry VIII, the hospital is still going strong after nine hundred years, and affectionately known as “Barts”.

At the Reformation, the income from the fair that had previously gone to the priory and its hospital, which had cared for the poor, passed to the aptly named Sir Richard Rich, Lord Chancellor in the reign of Henry VIII’s son Edward VI. The Rich family were involved with the fair until the nineteenth century. As far as the fair was concerned, it was business as usual.

Taking place on land belonging to the priory outside Aldersgate, Bartholomew Fair was originally a cloth market. The charter granted the right to hold this fair annually for three days beginning on 24th August. The sale of wool and cloth was an essential element in in England’s domestic and export economies. The importance of the cloth sales, and proximity to Smithfield Market, made Bartholomew Fair one of the most lucrative and bustling events in England. The crowds thronging to the fair needed entertaining and amusing as well as feeding and watering (except it was usually aleing, beering, and cidering rather than watering).

As one of London’s leading events, it was opened by the Lord Mayor of London. On St Bartholomew’s Eve, the Lord Mayor and other dignitaries rode out in violet robes for the official crying of the fair. A German visitor to the city, Paul Hentzner, described the procession and official opening in 1604. The visitors and traders were exhorted to behave themselves, to sell goods of the right quantity and quality, and not to sell goods on a Sunday. If anyone was unhappy with treatment they had received at the fair, they had recourse to the special courts associated with it, which were known as the Courts of Piepowder. Justice was overseen by the Lords of the Fair (originally the priors) with a jury of tradesmen, though all they could try were commercial cases. Piepowder was said to derive from the dusty feet of pilgrims, Pieds Poudreux, which turns up in English texts as the rather Tolkienesque Dustyfoot or Dustyfeet, and in Scotland as Dustyfute.

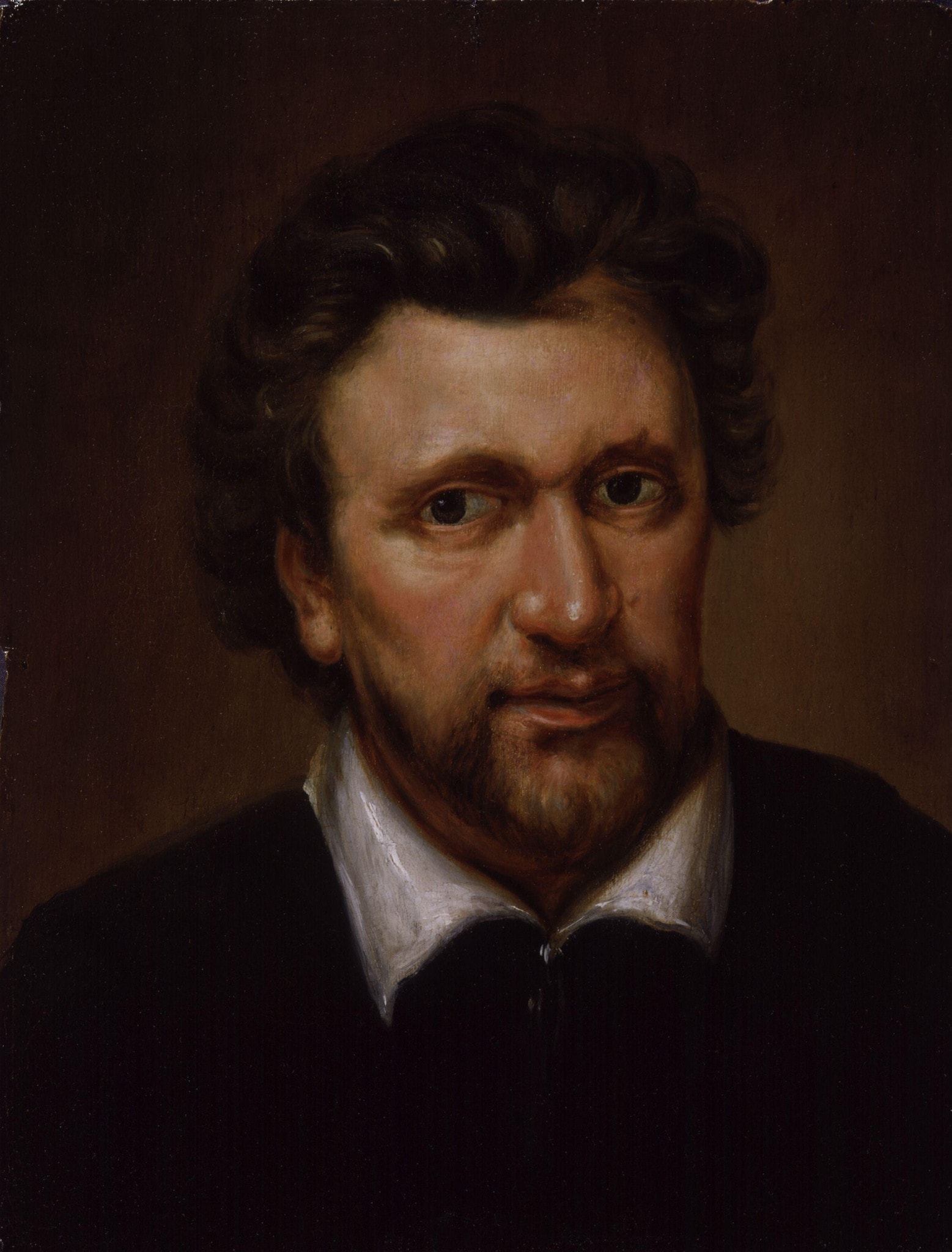

There were plenty of them to raise the dust, too: “Gentlemen, have a little patience, they are e’en upon coming, instantly.” With the thrill of anticipation shared by happy fairgoers and theatre audiences, thus opens Ben Jonson’s play Bartholmew Fair, first produced in 1614 at the Hope Theatre in London. By this time, the centuries-old Fair was famous – or rather notorious – for the various pleasures it offered. Jonson introduced his audience to a cast of roguish and meddlesome characters, mostly out for self-advancement and ripe for a fall. And the noise! Bartholmew Fair must surely be one of the most frantic and noisy plays in the whole of English drama, just like the fair itself.

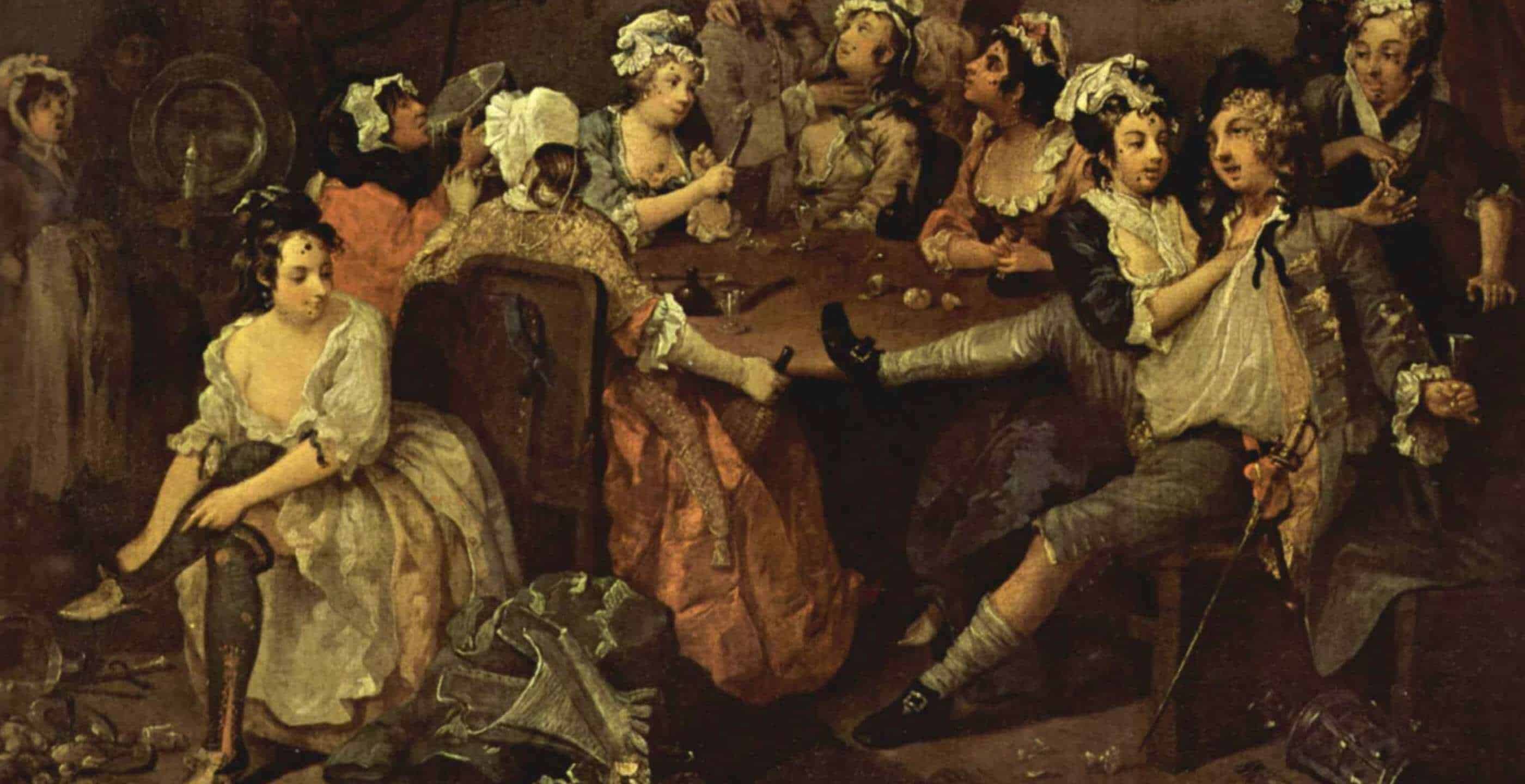

Here are to be found dubious horse dealers, provincial dupes, cut-purses and incompetent lawmen, Ursla the pig-woman who has much more than pork for sale, religious zealots, and a cast of insolent puppets. Bartholomew Fair was famous for its roasted pig meat, hobby-horses, and Bartholomew Babies, a wooden doll popular with fairgoers. It was traditional for lovers to buy them for their sweethearts when they went to the fair. Bartholomew Fair was the place for flirting and seductions, and “Bartholomew Baby” also became a term for someone who was a bit the worse for drink. Puppet shows were not unique to Bartholomew Fair, but the Bartholomew puppet shows were reckoned to be some of the best. There were also Jack Puddings and Merry Andrews, clowning comedians.

By the seventeenth century, the fair had stretched out to two weeks, before being curtailed back to four days in 1691. A publication of 1641 describes some of the delights on offer: “a knave in a fool’s coat, with a trumpet sounding, or on a drum beating”, literally drumming up an audience for the puppet-show. “A rogue like a wild woodman, or in an antic shape like an incubus”; a magician luring the visitor to watch his “hocus pocus, with three yards of tape or ribbon in his hand”. There were opportunities for betting, gambling, drinking, and eating pies and pork, the continuing speciality of Bartholomew Fair. According to the 1641 publication, “pigs are all hours of the day on the stalls, piping hot, and would cry, (if they could speak,) ‘Come, eat me!’”

The riotous atmosphere of Bartholomew Fair in 1641 was clearly still as it had been in Jonson’s day. However, the events of the mid-seventeenth century were a reminder to Londoners and visitors alike that life was not all beer, skittles, and the fun of the fair. John Evelyn wrote in his diary on 28th August, 1648: “To London from Sayes Court, and saw the celebrated follies of Bartholomew Fair”, without elucidating what those “follies” were. Less than six months later, in sober mood, he would be writing with horror of the execution of King Charles I.

On the restoration of King Charles II, Evelyn was much more forthcoming about a visit to another of London’s favourite fairs, that of St Margaret. He recorded on 13th September 1660 that he had seen tightrope walking monkeys and apes, dressed in human clothing. There were monkey rope walkers at Bartholomew Fair as well. Performing animals were some of the sights to be seen, as later were human beings from far-flung locations across the globe, viewed as exotic novelties by the gawping crowds.

The puppet-shows may have disappeared during the years of the Commonwealth, but they were back in force after the Restoration. On one of his visits to Bartholomew Fair, Samuel Pepys realised that the crowd around one of the puppet-shows was waiting for Lady Castlemaine, the king’s mistress, to come out. Expecting the celebrated beauty to be mobbed (he was a fan of Castlemaine himself at the beginning of Charles II’s reign), Pepys was surprised to see her out in public. She was often on the receiving end of antagonism since she was blamed for the king’s indolence and inattention to his regal duties. However, there was no unseemly response from the crowd on this occasion, and Castlemaine simply stepped into her coach and was driven away, like any modern celebrity at some media award ceremony; a muppet movie, perhaps.

Performing horses and pigs were two of the biggest draws of the fair from the seventeenth century onward. On one of his visits to Bartholomew Fair, Pepys encountered an intelligent mare that certainly had his measure. He described her as “the mare that tells money and many things to admiration”. Her showman owner asked her to select from the crowd the person who “most loved to kiss a pretty wench in a corner”. Unhesitatingly she went over to Pepys and chose him. Realising the joke was on him, and perhaps appreciating it, he paid over 12d (one shilling) “to the horse”. He also appears to have felt the need to prove his reputation by kissing “a mighty belle fille”.

The changing of the calendar in the eighteenth century meant that the fair shifted its opening date to 3rd September. Given frequently riotous behaviour at the fair, and the riots that accompanied the changes to the calendar, it’s more than likely that this caused a few complaints. There were attempts to close the whole thing down in the eighteenth century, given its continuing association with trouble, but due to its popularity the fair kept on going.

The showmen continued to present as many novelties and crowd-pullers as they could: seven-legged horses, calves with two heads, prize-fighters, swordsmen, and wild beasts. Giovanni Battista Belzoni, famed for his time in Egypt where he investigated the monuments (though brutally in some instances), was one of the visitors to Bartholomew Fair who became a sideshow. At six feet seven inches high, he was presented by one of the showmen in 1803 as “The Young Hercules” and “The Patagonian Samson”.

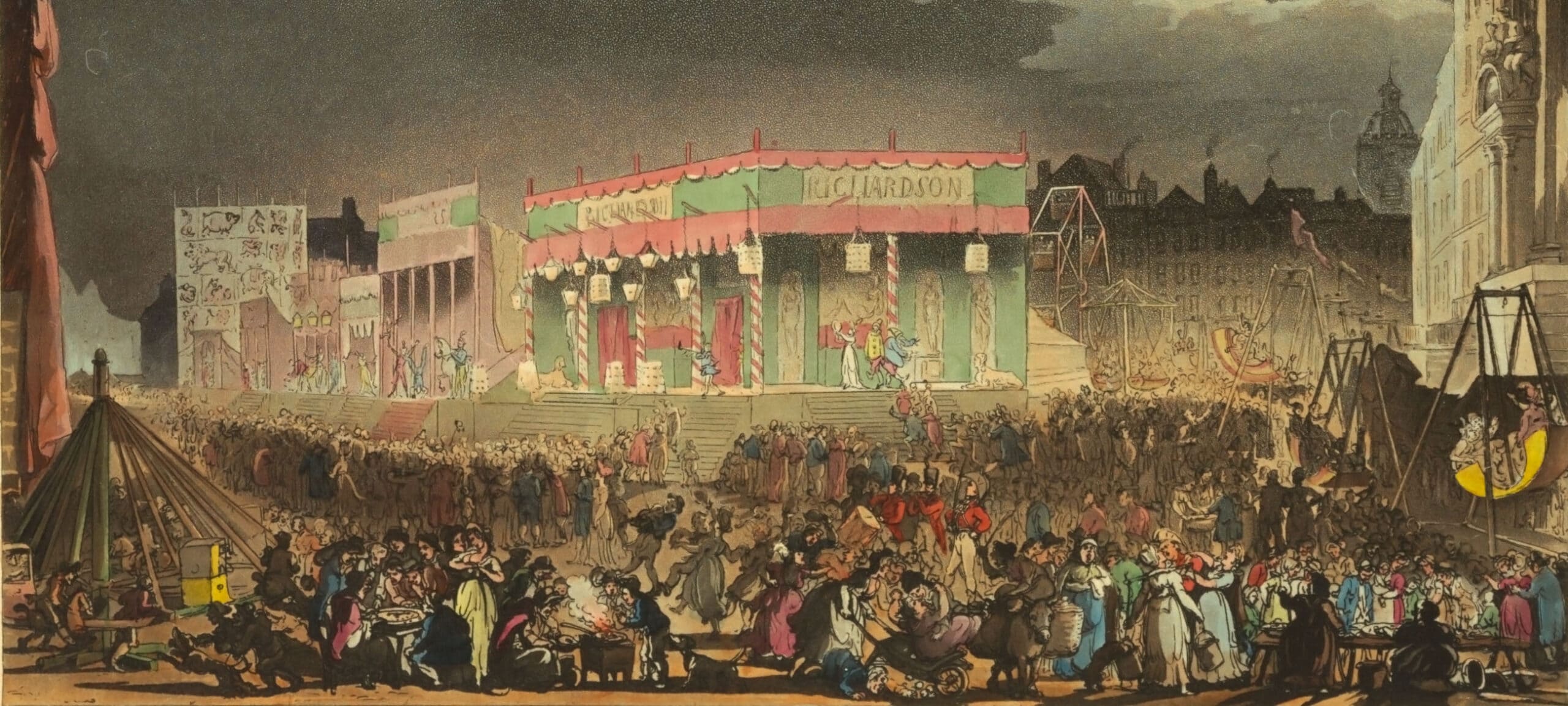

Henry Morley, author of Memories of Bartholomew Fair recalled his experience of visiting the fair early in the nineteenth century. He writes with nostalgia about “the memory of twilight with the glare of fires, candles, and oil lamps”, along with the dirt, drums, trumpets, spangled dancers, and irresistible booths sparkling with lights and decorations. There were peepshows, and the “tented gingerbread all armed in gold”. Gilt gingerbread was another essential element of fairs and had been since medieval times. Morley recalled the “cheap sweets, and dirty people asquat over sausages and kindred meat-stuffs, cooking at rows of fires upon the ground on each side of a dirty path into the Fair”. His descriptions vividly bring to life an experience that Ben Jonson and even Rahere would still have recognised.

Bartholomew Fair, with its essentially medieval ribaldry, sideshows, and generally anarchic atmosphere, was increasingly looked on askance by the authorities as a den of vice. By 1855, the show was finally over, shut down for causing too many public disturbances. The days of sausages, sin, and cider were no more. However, the City of London revived the event in 2023, putting on shows between the 31 August and 16 September in “a reimagining of a historic event with a modern twist”. These included aerial dance performances outside the cathedral, and walking tours in the heart of the City of London, continuing the secular and sacred, popular and commercial, spirit of old St Bartholomew’s Fair.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 29th January 2024