Sixteenth century almanacs reveal the way in which weather and the calendar were used to predict death and disaster in the Tudor period.

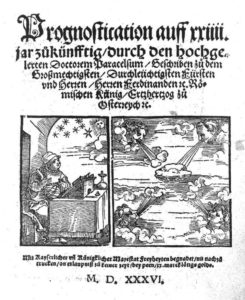

Paracelsus’ Prognostication on the Future, 1536

Paracelsus’ Prognostication on the Future, 1536

In the sixteenth century, almanac books were popular in most working households, packed full of handy information such as dates of religious importance, times of sunrise and sunset and the days and locations of annual fairs. However, the versions which are especially interesting are those with ‘prognostications’ (predictions) for the year ahead attached, based on the astrological beliefs and understandings of the period.

Some even marketed themselves as ‘prognostications everlasting’, meaning that they contained reusable methods of prediction, such as observing the weather, to allow the readers to prepare themselves for what was coming, and the chances were, it wasn’t pleasant. Why not take a leaf out of the Tudors book and follow these simple rules to ensure that plague, war, death, and wine shortages, won’t catch you unawares.

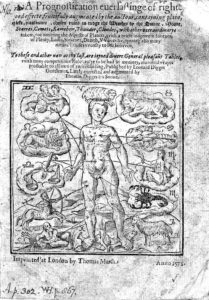

Erra Pater wrote the Prognostication Everlasting in 1535

Erra Pater wrote the Prognostication Everlasting in 1535

Weather

Thunder, believed to be the quenching of fire (i.e. lightning) in the sky, was thought to predict the future, depending on the day of the week it appeared. If it thundered on a Tuesday or Thursday this was great news, as it suggested that the harvest would bring a good amount of corn. Thunder on any other day of the week however, foretold death of judges, women and ‘great men’, and stormy Saturdays were definitely to be avoided as they denoted the arrival of a deathly pestilence. The time of day thunder appeared was also important as it predicted the weather that would soon follow: thunder in the morning suggested wind, at noon it predicted rain and if it thundered in the evening you would want to rush on home- in order to avoid the great tempest which was suspected to be on its way.

A weather forecast could also be gained from rainbows. If rainbows accompanied foul weather, then fair weather was due and conversely if a rainbow appeared and the weather was good… it was probably best to remain indoors. While glancing up at the sky, you could take a look at the clouds. Mostly these will be harmless, for example, dark clouds signified rain and long lasting white clouds suggested snow, however you would want to be wary of any resembling pillars as these were considered the sign of impending earthquakes. Earthquakes were also predicted by the sight of a comet, which were believed to signify in themselves a corruption of the air. The sighting of comets could also foretell war and death, meaning you probably wouldn’t have been as excited to witness one in the sixteenth century as you might be today.

Days

The weather on specific days, such as Christmas day, could be used to gauge the fates of those around you for the upcoming year. Wind on this day was a particularly bad omen, predicting the death of cattle if appearing at sunrise, daily sickness if at midday and death of kings and lords if wind was felt at sunset. If there was no wind at all, the outcome looked much brighter as you could expect plenty of fruit and wine in the following year.

Leonard Digges’ Prognostication Everlasting

Leonard Digges’ Prognostication Everlasting

Twelve Days of Christmas

There was also a belief that the twelve days of Christmas correlated to the twelve months of the year and therefore the weather on each of these days would provide a prediction for the matching month. For example, if the sun shone on Christmas Day then this could signify a peaceful start to the year, however if the day was windy, then January would bring the death of a great man. Sun on the fifth day would lead you to expect plenty of fruit and herbs in May, however if it happened to be windy on that day then you might’ve wanted to give up reading for the time being as there would be great death among ‘learned’ people that month. Sun on the tenth day may suggest ‘evil weather’ in October, and the death of cattle should the day be windy. The outlook for December is fairly grim and un-festive, with both sun and wind on the twelfth day predicting war for the end of the year.

New Years’ Day

As well as weather being utilised to predict the year, the day of the week on which New Years’ Day fell was considered an omen for the following twelve months. These predictions typically focused on the weather, harvests, in particular how much fruit, wine, corn and honey there would be, and who was likely to fall on hard times. A Sunday, for example, predicted a hot summer and an abundance of fruit but also robberies and the death of many young people. Mondays were similar in this pattern of blessing and curse, being an omen of floods, death of women and lords but also an abundance of corn and wine. These dark predictions continue with a Tuesday suggesting fire, Wednesday the death of children, cattle and some intriguingly described ‘naughty weather’, Thursday would indicate war, Friday earthquakes and finally a New Year’s Day which landed on a Saturday would foretell many murders that year.

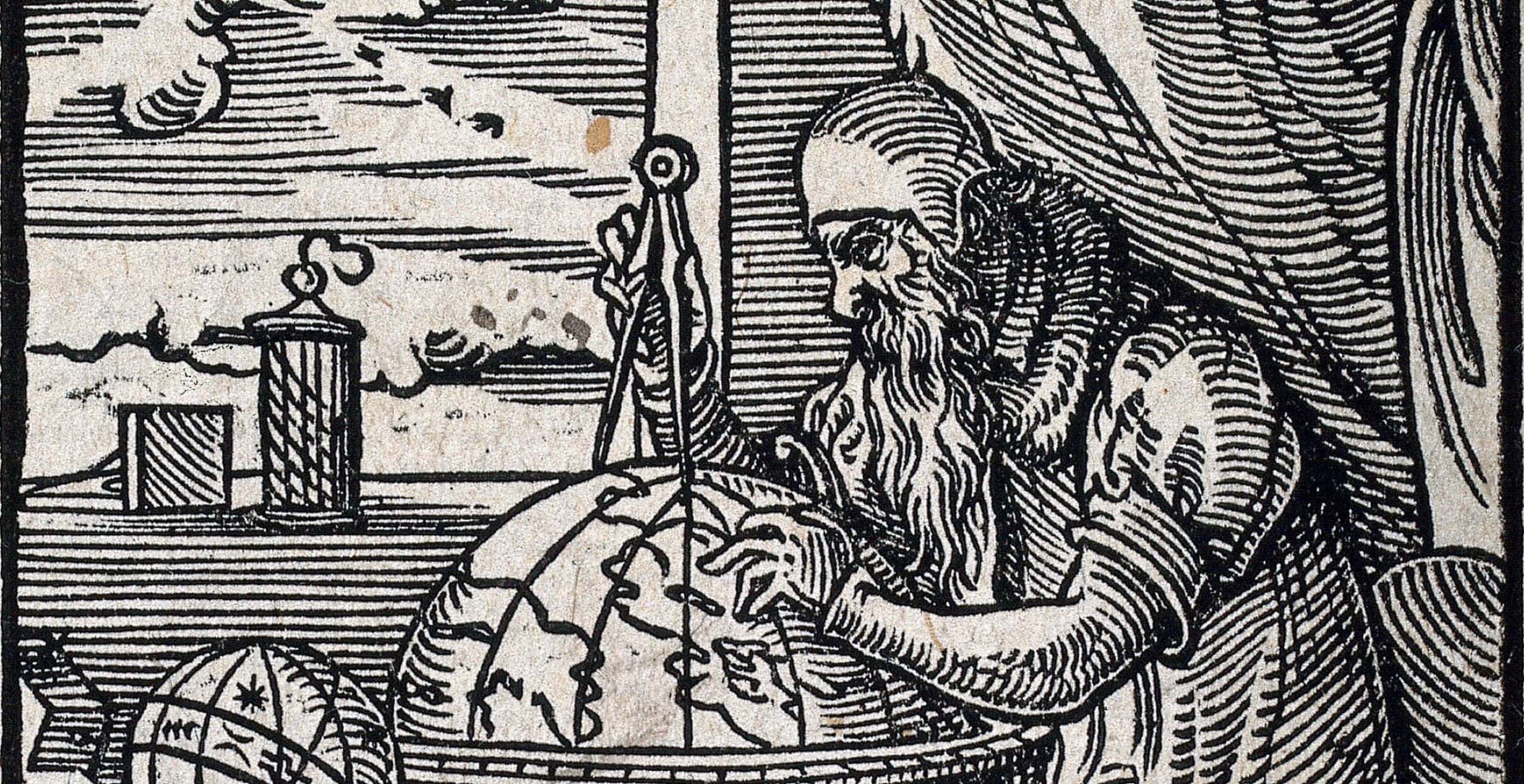

An astrologer in his study, by Jost Anman, 1568

An astrologer in his study, by Jost Anman, 1568

While such predictions were printed and bought during the sixteenth century, we cannot of course definitively conclude that these were the common beliefs of that time. However, as the three prognostications from which this information was taken were printed in 1535, 1571 and 1585, and often mirrored each other in their concepts, it does suggest that these were common ideas that endured the period. These utterly fascinating books give an intriguing insight into the importance of the seasons, superstitions and the ways nature and time may have been used to provide a sense of readiness and certainty in what was a century of political and religious turmoil.

Anna Simms divides her time between primary school teaching and studying and is currently working towards an MSt in Historical Studies at the University of Oxford. She is particularly interested in belief, superstition and ideas in England during the late medieval to early modern period.

Published: 13th August 2021