The names of the great Scottish inventors role easily off the tongue; John Logie Baird (television), Alexander Graham Bell (telephone), Charles Macintosh (waterproofing), James Watt (steam engine pioneer) and John Dunlop inventor of the pneumatic tyre, or should that read re-inventor of the pneumatic tyre?

Indeed it should read re-inventor; the pneumatic tyre was in fact patented by one of Scotland’s most prolific, but now largely forgotten, inventors, Robert William Thomson on 10 December 1845, some 43 years before John Dunlop’s re-invention. Thomson’s “Aerial Wheels” were subsequently demonstrated in Regents Park London in 1847 and proved to all present that they could both reduce noise and improve passenger comfort. But who was Robert William Thomson, and what else did he invent?

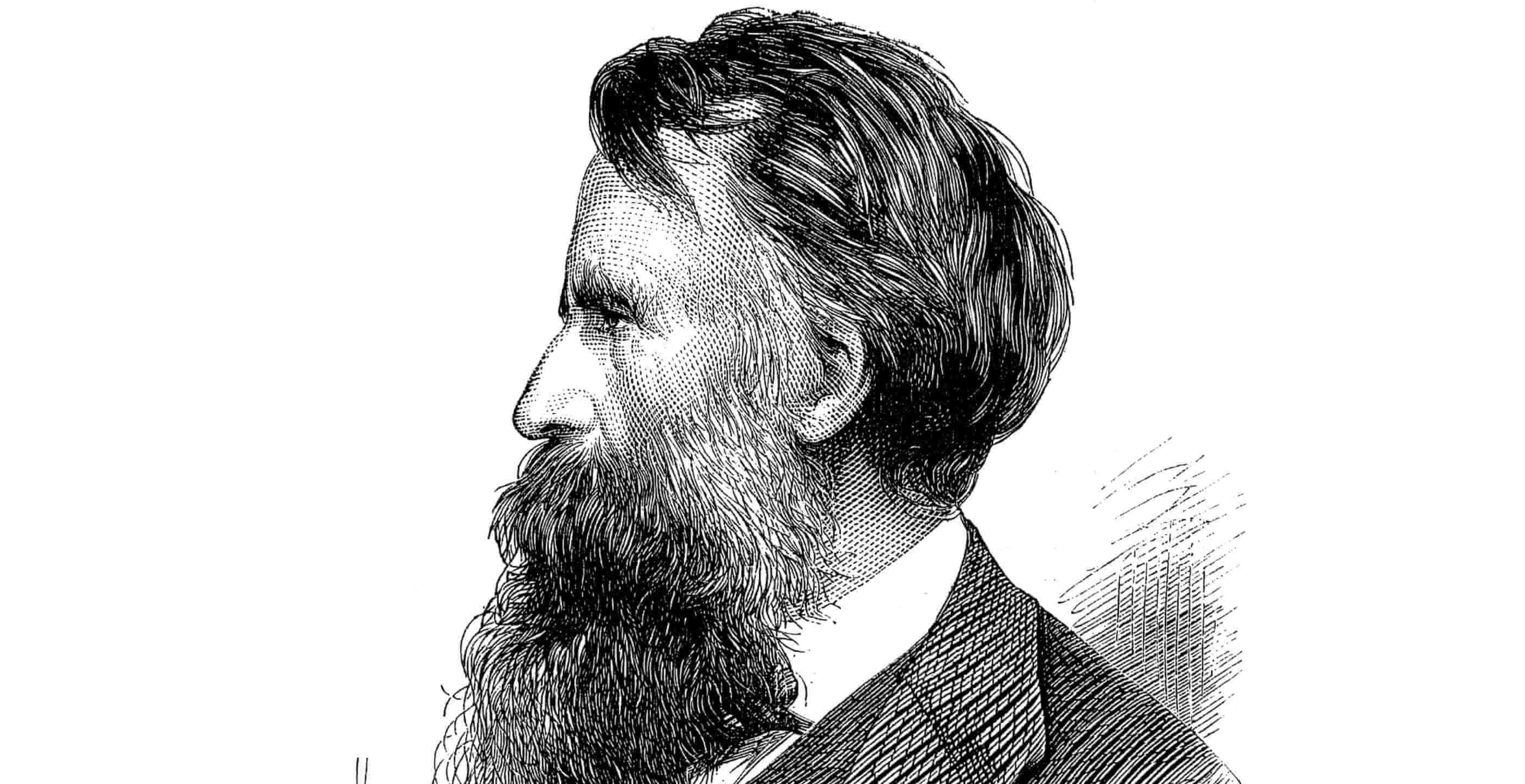

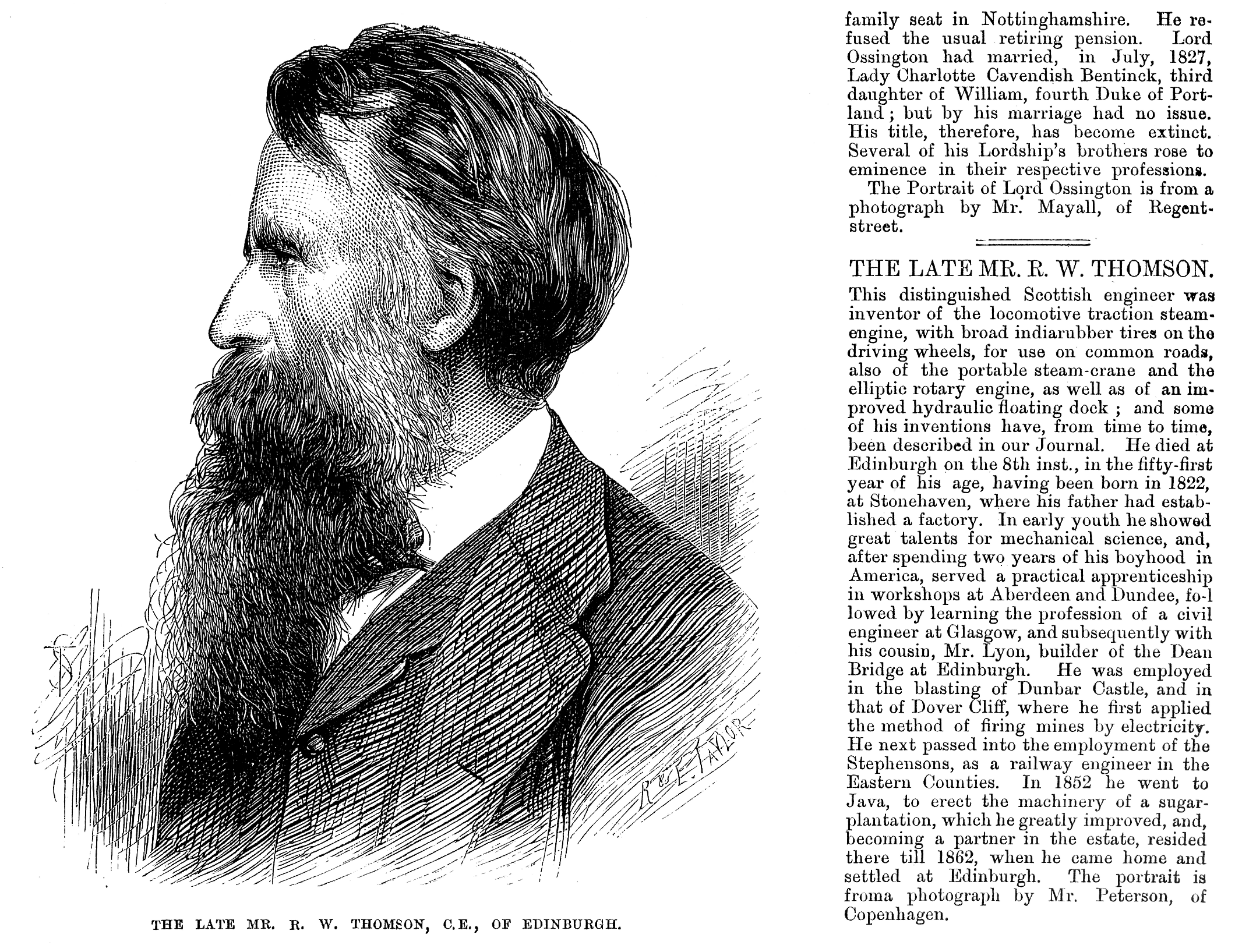

Robert was born in Stonehaven, on Scotland’s north east coast in 1822; he was the son of a local woollen mill owner and was the eleventh of twelve children. Originally destined for the ministry, he apparently had great difficulty coming to terms with Latin, and was therefore forced to consider an alternative career route.

Leaving school at 14, Robert was sent to stay with an uncle in Charleston in South Carolina, USA, in order to learn the trade of a merchant. But this apparently did not appeal to him either as he returned home two years later.

He then found something that he could do, and promptly taught himself chemistry, electricity and astronomy with assistance from a local weaver who had some knowledge of mathematics.

His father provided a workshop for him when he was just 17, and it appears that this inspired his creative and inventive side. He promptly re-designed, re-built and made substantial improvements to the workings of his mother’s washing mangle. He also designed and built a ribbon saw and a prototype rotary steam engine.

After serving his apprenticeship with an engineering firm in Aberdeen and Dundee, Robert started work in Edinburgh as an assistant to a civil engineer. Involved in some major building and demolition projects, he developed a method of detonating explosive charges remotely using electricity. Compared with the established “light the blue touch paper and run” routine of the day, Robert’s new and relatively safe technique must have saved countless lives over the years.

With the grand sum of nine pounds in his pocket, Robert set off for London looking for a fresh challenge and entered the rapidly expanding field of railway engineering. He started to work for the contractors Sir William Cubitt and Robert Stephenson, but eventually formed his own railway consultancy in 1844.

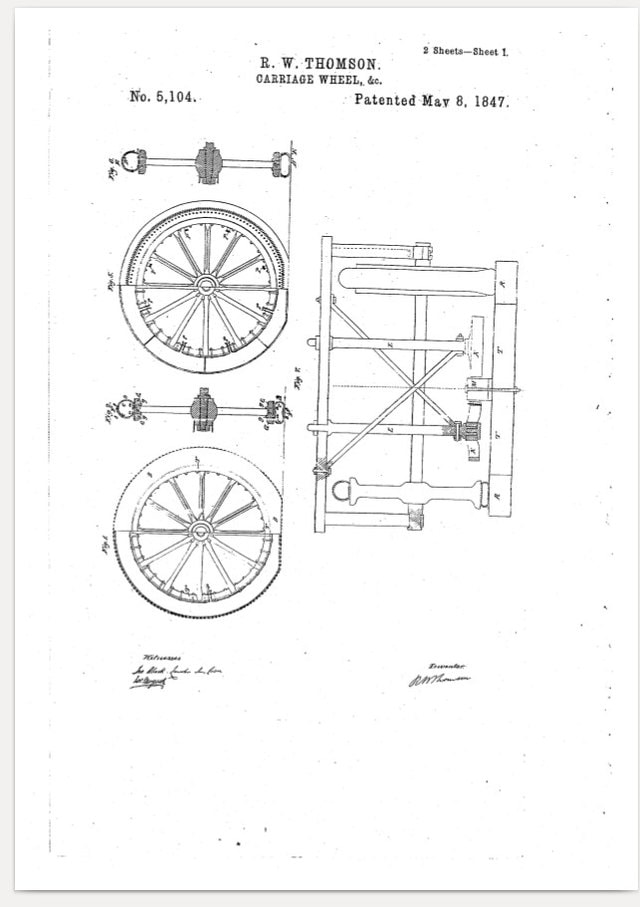

Thomson was only 23 when in 1845 he applied for the patent that would leave his mark on the world – Patent No 10990. The pneumatic rubber tyre – or “aerial wheel” as Thomson referred to it – would eventually transform road travel from an uncomfortable succession of bumps and jolts, to a quiet smooth ride by providing a cushion of air between the road and vehicle itself.

Despite the demonstrable advantages of the pneumatic tyre, Robert’s invention was some fifty years ahead of its time, as back in 1845, not only were there no motor cars, but bicycles were only just starting to appear on town and city streets. This lack of demand together with the high production costs reduced pneumatic tyres to a mere curiosity.

Undeterred, Robert went on to patent the principle of the fountain pen in 1849.

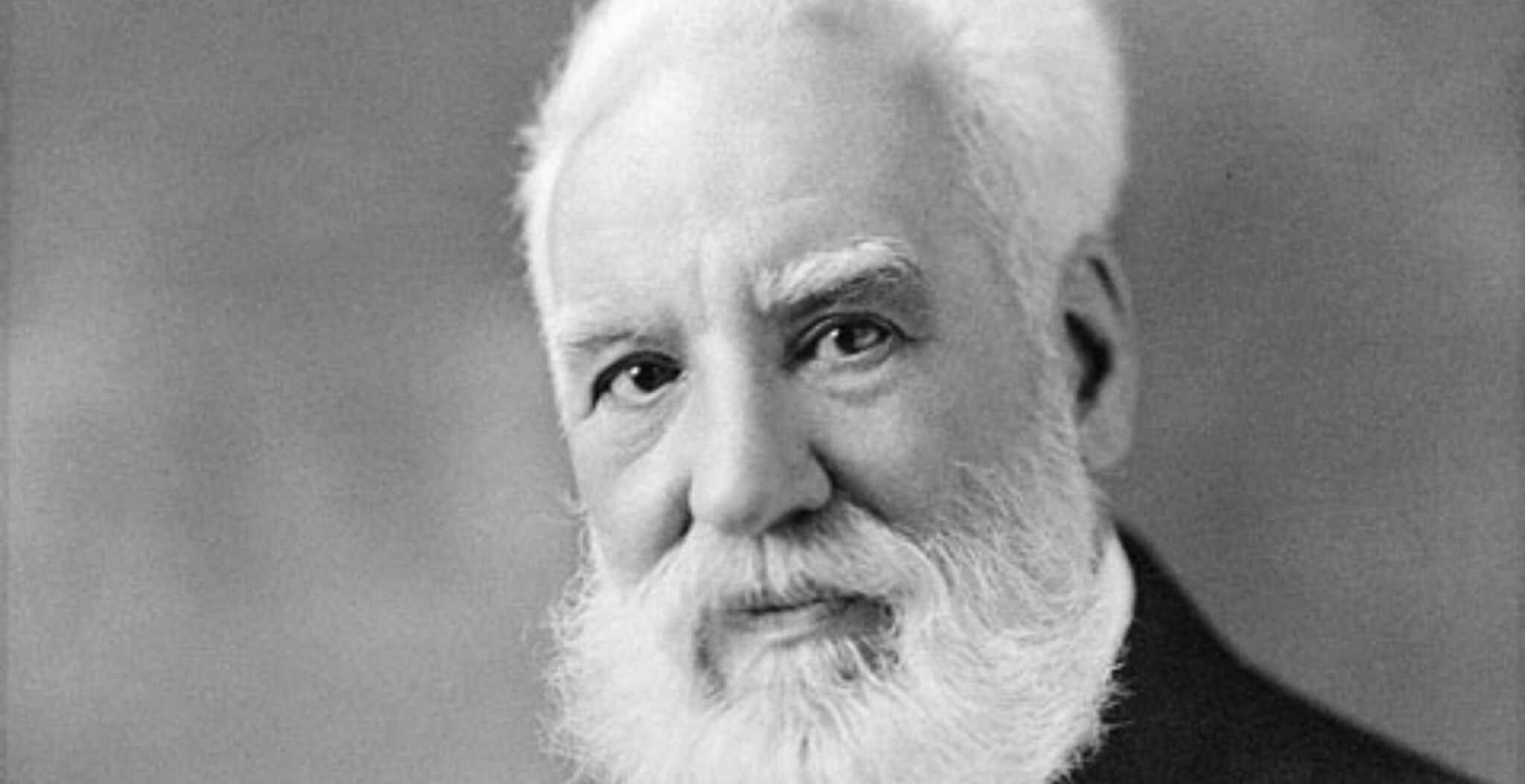

In 1852 Robert accepted a post in Java, working as a sugar plantation engineer improving existing machinery for the production of sugar and designing new equipment, including the first mobile steam crane and a hydraulic dry dock. It was also whilst in Java that he met and married Clara Hertz, with whom he had two sons and two daughters. The family eventually returned to Edinburgh in 1862, due to Robert’s ill-health.

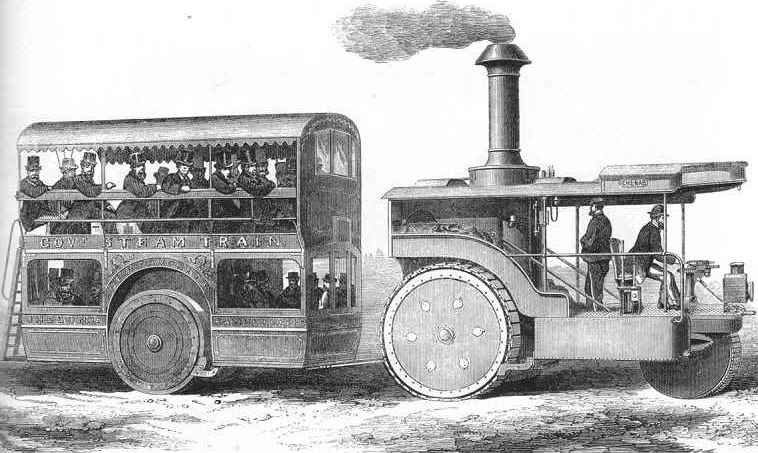

His ill-health does not appear to have slowed Robert down though, as in 1867 he developed the first successful mechanical road haulage vehicle, a steam traction engine. In addition, he patented solid india-rubber tyres which meant that his heavy steam engines could travel along the roads without damage to the surface. By 1870 ‘Thomson Steamers’ were being manufactured and exported around the world.

Robert died on 8 March 1873 at his home in Moray Place, Edinburgh, at the relatively early age of 50 and was buried in Dean Cemetery. But even this didn’t slow him down as the last of the fourteen patents registered to his name, this time for elastic belts, was filed later that year by his wife, Clara.

It would be some 15 years after this that another Scot, John Boyd Dunlop, would re-invent Robert Thomson’s pneumatic rubber tyre. Only this time the world had caught up, bicycles were now common place and those new-fangled motor cars were beginning to appear, and so it was that the name of Dunlop rather than Thomson would be recorded in the history books.

A bronze plaque that commemorates the anniversary of Robert Thomson’s birth can now be found on a building to the south side of Stonehaven’s Market Square. Each year in June, vintage vehicle owners and their machines gather for a Sunday rally in honour of the great man.