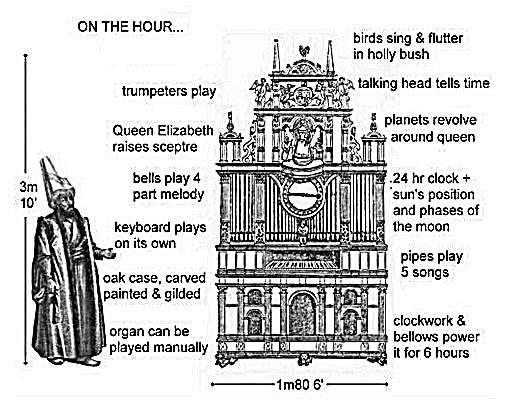

As diplomatic gifts go, a musical organ must rank amongst the quirkiest. When the organ is 16 feet high, plays tunes automatically four times a day, has a 24-hour clock and is decorated on top with “a holly bush full of blacke birds and thrushis” which “sing and shake theire winges” the gift enters the realm of the surreal.

To cap it all, the organ was a present from Queen Elizabeth I to Sultan Mehmed III as part of an overture to establish a cordial relationship between the two rulers. It must have seemed like a good idea at the time, and so it proved to be.

The 16th century saw the expansion of global trade and the establishment of England as an international maritime nation. Creating and maintaining a sound relationship between England and Turkey was vitally important for the success of England’s ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean in the late 16th century.

With the Spanish and Portuguese now controlling trade round the Cape, English merchants were pressing for safe-conduct and the right to trade directly with the Sultan’s dominions. Previously trade had usually gone through intermediaries such as the Venetians and merchant ships from Flanders. When these connections failed, trade with the eastern Mediterranean dried up completely.

By playing on the common enemy of both England and Sultan Murad III – Spain – English negotiators opened up diplomatic negotiations between the two powers. Some very flowery compliments flowed in the direction of Elizabeth from the Sultan (“cloud of most pleasant raine, and sweetest fountaine of noblenesse and virtue”), while some cordial but typically authoritative greetings flowed back from Her Majesty to the man they called “The Grand Turk” (“From Elizabeth, the most invincible and most mighty defender of the Christian faith against all kind of idolatries…to the most sovereign Monarch of the East Empire”). Elizabeth’s intention was to prove to the Sultan that Protestant England and the Islamic world had much in common. In 1580, Sultan Murad III granted a charter of privileges to English merchants.

All was going swimmingly until the French ambassador objected and the agreement fell apart. Negotiations began all over again and in 1592, Elizabeth granted a charter for a new company, “The Governor and Company of Merchants of the Levant”. When Murad died and Mehmet III became Sultan, the time was right for a new diplomatic mission to cement the rights of the English in the Sultan‘s dominions.

Quite why the principal gift from Elizabeth to Mehmet III should have been a fantastical Disney-style organ is not immediately clear.

However, the best man for the job was Thomas Dallam, a Lancashire-born craftsman who had come to London to study organ-building with a member of the Blacksmiths’ Company. While he would later become well-known as an organ builder, achieving fame for creating the organ for King’s College Chapel at Cambridge University, nothing is known of his work prior to his being commissioned for the gift to the Sultan.

Dallam was not only commissioned to build the organ, but also to travel with it to Constantinople and oversee its installation. Fortunately for historians, Dallam left a diary of his voyage there and back, which is full of entertaining tales. First published by the Hakluyt Society in the late 19th century, the diary combines a great sense of wonderment with a no-nonsense approach to life’s challenges. Dallam comes over as a man with a great deal of natural curiosity about the world while also being down-to-earth and pragmatic.

The journey was a great adventure right from the start. Dallam was sailing on the merchantman Hector, chartered on behalf of the Merchants of the Levant Company under Captain Richard Parsons. They hadn’t cleared the Channel when a ship that had been attacked by “Dunkirkers”, who were always on the lookout for rich prizes, warned them that seven ships of the pirates from Dunkirk were wanting to know the whereabouts of the Hector.

The merchantman was well equipped with guns and engaged with the ships to great effect. However, although he had the chance to sink or capture the ships, Captain Parson agreed to let them go which disgusted everyone on board the Hector, Dallam included.

They were now properly on their way, and Dallam noted in his diary the marvellous antics of dolphins (“porpoisis”) and the impressive spouting of whales. He had brought a set of virginals (an early type of harpsichord) with him, and played both for his own amusement and the enjoyment of the crew and other travellers.

They passed Gibraltar and sailed on into Algiers harbour, where he went ashore with a small party to explore. This was where Dallam hit his first snag and also showed his mettle – the King of Algiers got word of the fabulous gift that was on its way to the Sultan, and wanted to see it. Captain Parsons was to be held hostage in the meantime.

Somehow, Dallam negotiated his way out of a tricky situation. With the organ carefully packed up, it would have been impossible to bring it out and set it up for the King. Soon they were under sail once more, heading for the beautiful island of Zante.

Dallam was eager to explore a mountain that he spotted on the island, but his two companions, Michael Watson, his joiner, and Ned Hale, a coachman, were more cautious. As he headed off adventurously, the others came along reluctantly, only to get into a flap at their first sight of a shepherd carrying a large club to protect himself.

Nothing daunted, Dallam was clearly fascinated by the different culture and pleased to be invited by a hospitable local to join him in his house on the mountainside. Feeling thirsty, he gladly accepted some wine despite the cautionary words of Ned Hale who warned him that “he had no reason to drinke at there handes, nether to go any nearer them”.

While Michael Watson lay trembling in a bush and refused to come out, Dallam thoroughly enjoyed the Easter hospitality of coloured eggs, bread, cheese and “tow boules of wine” offered him, and attended a service at the nearby church. The freshness and clarity of his description comes over even 400 years later. He was clearly having a great time, even if his companions weren’t!

Throughout his journey, Dallam’s diary displays an openness and curiosity about people and places. His nature and sense of humour made him willing to think the best of people, and probably because of this, he was almost always met with warmth and hospitality.

At Scandaroune (modern day Iskanderun in Turkey) Dallam watched as a white pigeon flew into a merchant’s house, to be greeted with “Welcome, Honest Tom”. This was a carrier pigeon with a letter under his wing who had flown all the way from Aleppo in four hours.

Dallam noted it in his diary as they passed the ruins of Troy and listened to the echoes coming back from the great walls. He watched painted Turkish frigates coming down the Hellespont, and saw the naked rowers in the Turkish galleys. When on shore, he took a piece of a marble pillar he found in some ruins.

Finally they arrived at Constantinople and began to unpack the cases holding the organ, only to find that all the glued pieces had come apart through the heat in the hold and that some of the pipes were “brused and broken”. The ambassador and other English worthies in Constantinople doubted that the damage could be restored, but Dallam had faith in his skills.

He rebuilt the organ so that it worked to his high standards, sometimes with the King of Fez seated nearby watching him with interest. At last it was ready to present to the Sultan. Watching from behind the scenes, Dallam was thrilled and relieved to hear the results of all his hard work: “Firste the clocke strouke 22; than The chime of 16 bells went of, and played a songe of 4 partes. That beinge done, tow personagis which stood upon to corners of the seconde storie, houlding tow silver trumpetes in there handes, did lifte them to theire heads, and sounded a tantara. Than the muzicke went of, and the orgon played a songe of 5 partes…Divers other motions thare was which the Grand Sinyor wondered at.”

Dallam had been warned that he would not be allowed into the presence of the Sultan and so he was shocked to hear that the Sultan, not content with the clockwork parts that worked automatically, wanted to hear it played by someone with skill.

Explaining that in order to play it he would have to be so close to the seated Sultan that they would almost be touching, and that he would also have to turn his back to the ruler, a grave (and possibly fatal) breach of court etiquette, he nonetheless went out to fulfil the request.

There stood Dallam, in front of the gorgeously bedecked court, bowing his head to his knee, then he turned away so his “britches” even brushed the Sultan’s knee, and began to play. The powerful ruler was delighted with Dallam’s musical performance and loaded him with gold. In fact, it was touch-and-go for a while whether he would be allowed to leave the great city, and Dallam grew very homesick, but eventually he made it back to England with some astonishing tales to tell!

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.