William Laud was a significant religious and political advisor during the personal rule of King Charles I. During his time as the Archbishop of Canterbury, Laud attempted to impose order and unity on the Church of England through implementing a series of religious reforms that attacked the strict Protestant practices of English Puritans. Accused of popery, tyranny and treason, Laud was considered one of the key instigators of the conflict between the monarchy and Parliament, which ultimately paved the way for the English Civil War.

Laud’s real political significance began in 1625, when Charles I came to the throne. As an immediate royal favourite, Laud was able to capitalise on Charles’ support through advocating the theory of the Divine Right of Kings, arguing that Charles had been chosen to rule by God. The assassination of one of the King’s main advisors and Laud’s patron, the Duke of Buckingham in 1628, intensified the influence of Laud who promised to protect Charles from these ‘bad Christians’ who threatened the Crown. This coincided with Charles’ deteriorating relationship with Parliament and the beginnings of his Personal Rule (1629- 1640), in which Parliament was suspended for eleven years. Laud was then appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633, which kick-started the Laudian reforms on the Church of England.

During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, the Church became progressively Calvinist in doctrine, which corresponded with the increasing number of Puritans in England. Despite this, Laud openly criticised the nature of the Church throughout his career, arguing that church dogma had become too Calvinist, services too stern and the Crown too involved in religious matters. Laud found backing in his quest for reform from the King and prominent noblemen, as a result of their growing support for Arminianism. This was a strand of Protestantism that rejected some of the key Calvinist doctrines, such as predestination, and instead focussed on the belief that salvation could be achieved through free will.

Moreover, one of Laud’s most controversial actions was his determination to restore church buildings to reflect the aesthetic grandeur of the pre-Reformation church. His conscious effort to reinstate the ‘beauty of holiness’ ensured that traditional clergy vestments, images and stained glass windows re-emerged in churches and cathedrals in order to reflect the divinity of God’s presence on earth. The blatant reference to the Catholic traditions of celebrating icons and elaborate church designs angered Puritans and intensified their concern that Laud was reviving Catholic practices within the established church. This became a particular issue in the early 1630s, when Laud ordered parishes to replicate the imagery of cathedrals, most notably the position of the communion table. The order decreed that the communion table should be made out of stone, not wood, and had to be placed against the east wall of the chancel surrounded by railings, therefore the laity had to kneel at the rails in order to receive communion. The emphasis on Catholic spirituality and superstition was an immediate concern to Puritans who considered the changes intrinsically linked to the Roman Catholic Mass: consequently, protests against the order occurred immediately.

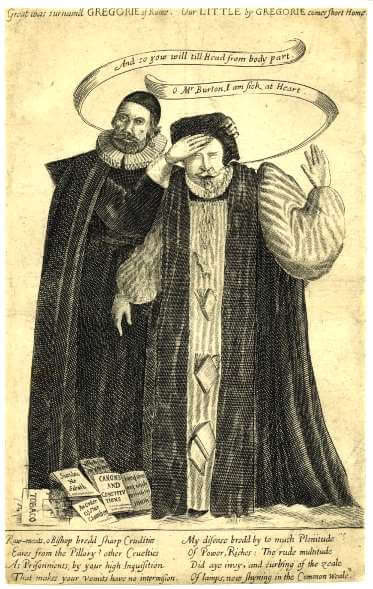

To enforce these changes and punish non-conformists, Laud conducted visitations of parish churches. The visitations were intrusive and ensured that every aspect of the aesthetic and doctrinal policies were in place. Laud’s persistent attack on non-conformists was intensified in 1637 when Puritan writers, William Prynne, Henry Burton and John Bastwick were sentenced to have their ears removed and cheeks branded after publishing writings against Laud. This was considered a shocking and unnecessary punishment which accentuated the resentment staunch Protestants felt towards Laud and the Church, and created Puritan martyrs out of the victims.

By Abigail Sparkes

Postgraduate student at the University of Birmingham, currently studying for a Master’s Degree in early modern history.

Published: 2nd January 2018