Not Waterloo but Peterloo!

England is not a country of frequent revolutions; some say it is because our weather is not conducive to outdoor marches and riots.

However, weather or no weather, in the early 1800’s, working men began to demonstrate on the streets and demand changes in their working lives.

In March 1817, six hundred workers set off from the northern city of Manchester to march to London. These demonstrators became known the ‘Blanketeers’ as each carried a blanket. The blanket was carried for warmth during the long nights on the road.

Only one ‘Blanketeer’ managed to reach London, as the leaders were imprisoned and the ‘rank and file’ quickly dispersed.

In the same year, Jeremiah Brandreth led two hundred Derbyshire labourers to Nottingham in order, he said, to take part in a general insurrection. This was not a success and three of the leaders were executed for treason.

But in 1819 a more serious demonstration took place in Manchester at St. Peter’s Fields.

On that August day, the 16th, a large body of people, estimated to be around 60,000 strong, carrying banners bearing slogans against the Corn Laws and in favour of political reform, held a meeting at St. Peter’s Fields. Their major demand was for a voice in parliament, as at that time the industrial north was poorly represented. In the early 19th century just 2% of British people had the vote.

The magistrates of the day became alarmed at the size of the gathering and ordered the arrest of the principal speakers.

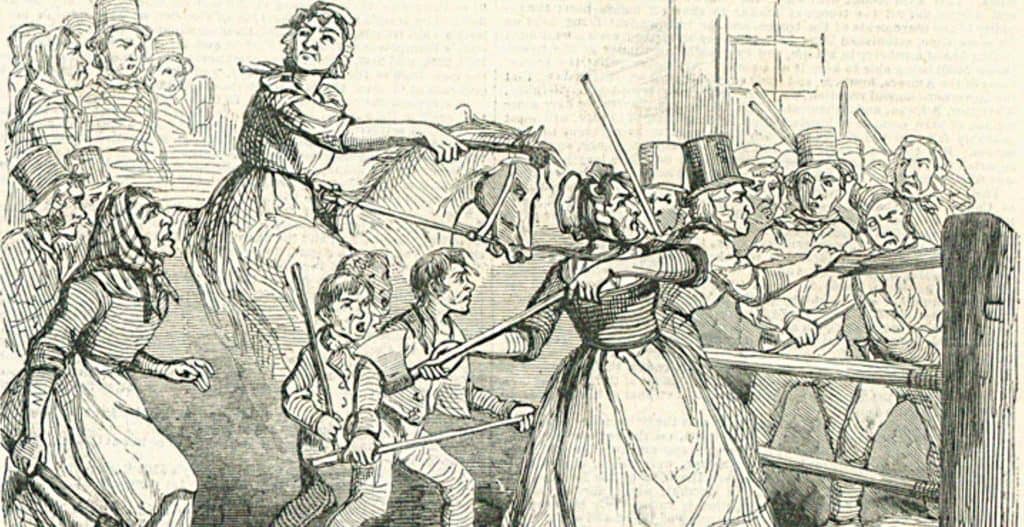

Attempting to obey the order the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (amateur cavalry used for home defence and to maintain public order) charged into the crowd, knocking down a woman and killing a child. Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, a radical speaker and agitator of the time was eventually apprehended.

The 15th The King’s Hussars, a cavalry regiment of the regular British Army, were then summoned to disperse the protesters. Sabres drawn they charged the massed gathering and in the general panic and chaos which followed, eleven people were killed and about six hundred injured.

This became known as the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. The name Peterloo first appeared in a local Manchester newspaper a few days after the massacre. The name was intended to mock the soldiers who attacked and killed unarmed civilians, comparing them with the heroes that had recently fought and returned from the battlefield of Waterloo.

The ‘massacre’ aroused great public indignation, but the government of the day stood by the magistrates and in 1819 passed a new law, called the Six Acts, to control future agitation.

The Six Acts were not popular; they consolidated the laws against further disturbances, which the magistrates at the time considered presaged revolution!

The people viewed these Six Acts with alarm as they allowed that any house could be searched, without a warrant, on suspicion of containing firearms and public meetings were virtually forbidden.

Periodicals were taxed so severely that they were priced beyond the reach of the poorer classes and the magistrates were given the power to seize any literature that was deemed seditious or blasphemous and any meeting in a parish that contained more than fifty people was deemed illegal.

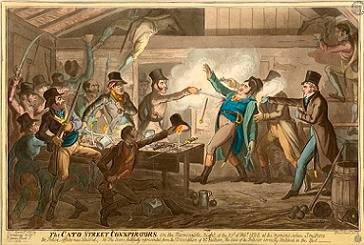

The Six Acts gave rise to a desperate response and a man called Arthur Thistlewood planned what was to become known as the Cato Street conspiracy….the murder of several cabinet ministers at dinner.

The conspiracy failed as one of the conspirators was a spy and informed his masters, the ministers, of the plot.

Thislewood was caught, found guilty of high treason and hanged in 1820.

The trial and execution of Thistlewood constituted the final act of a long succession of confrontation between government and desperate protestors, but the general opinion was that the government had gone too far in applauding ‘Peterloo’ and passing the Six Acts.

Eventually a more sober mood descended on the country and the revolutionary fever finally died out.

Today it is widely recognised however, that the Peter Massacre paved the way for Great Reform Act of 1832, which created new paliamentary seats, many in the industrial towns of northern England. A significant step in giving ordinary people the vote!

Published: 15th March 2015