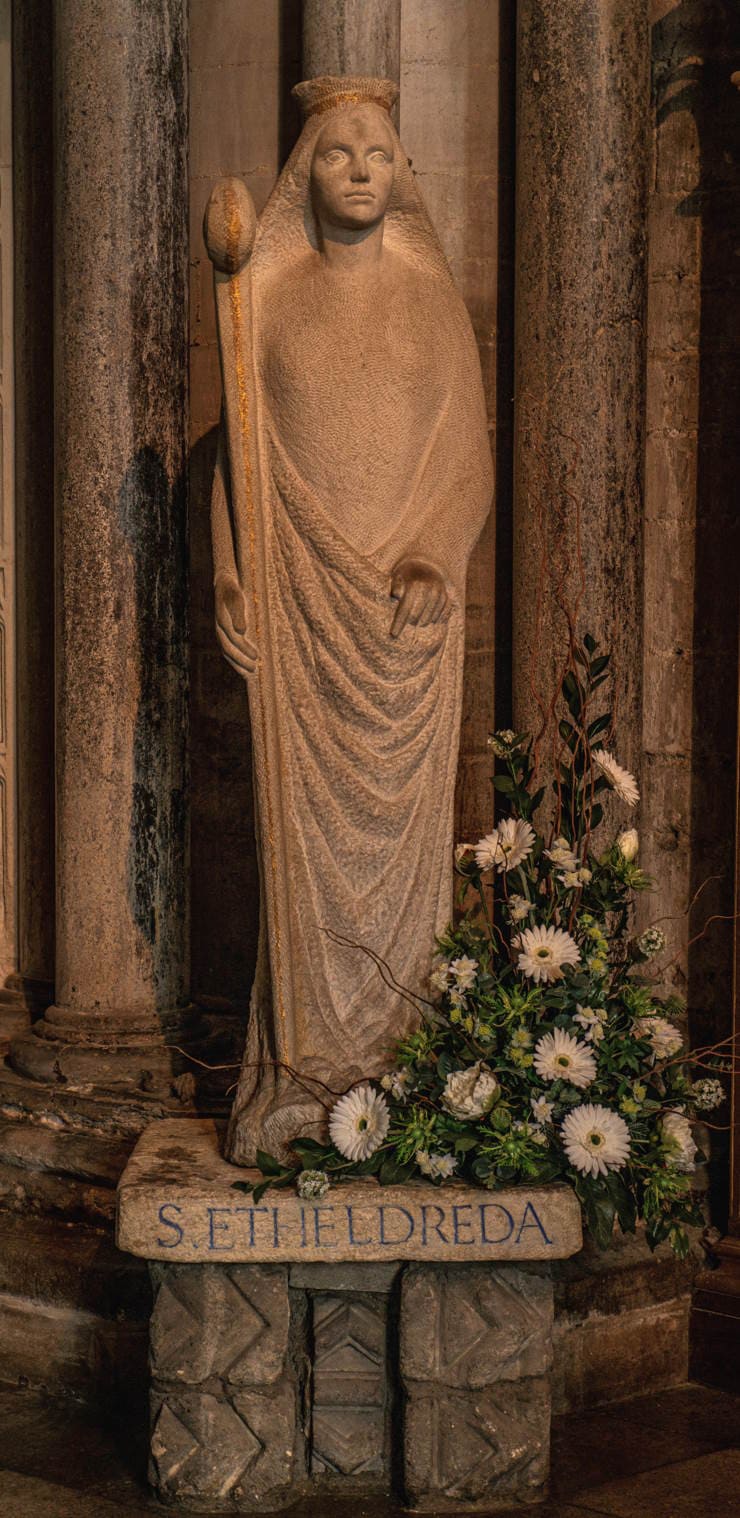

This year, Ely Cathedral celebrates the 1,350th anniversary of its origins in 673, when the Anglo-Saxon queen and saint Etheldreda (also known as Aethelthryth or Audrey) founded a monastery on, or near, the site of the modern cathedral. Although Etheldreda is little known today, she was once one of England’s most popular saints, and her shrine at Ely was a site of pilgrimage up to the Reformation.

The Anglo-Saxon historian Bede gives us the earliest known account of Etheldreda’s life in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which he completed in 731, around half a century after Etheldreda’s death. He tells us that she was the daughter of Anna, King of the East Angles, and that she was brought up in the Christian faith (at the time of her birth some kingdoms, notably Mercia, were still pagan).

Etheldreda entered into two arranged marriages. The first was to an ealdorman, or chieftain, of the local South Gyrwe tribe, a man named Tondberht, who died a few years later. She was then married to Ecgfrith, a prince of Northumbria. Ecgfrith and Etheldreda became King and Queen of Northumbria in 670.

It may seem surprising, in the circumstances, that Etheldreda was venerated as a virgin saint. In the early church, virginity was prized as the highest state of life for both men and women, and Bede is insistent that Etheldreda remained a virgin throughout both of her marriages. He says that he consulted Bishop Wilfrid, who had been Etheldreda’s spiritual advisor, on the subject, and that Wilfrid had unequivocally confirmed her virginity.

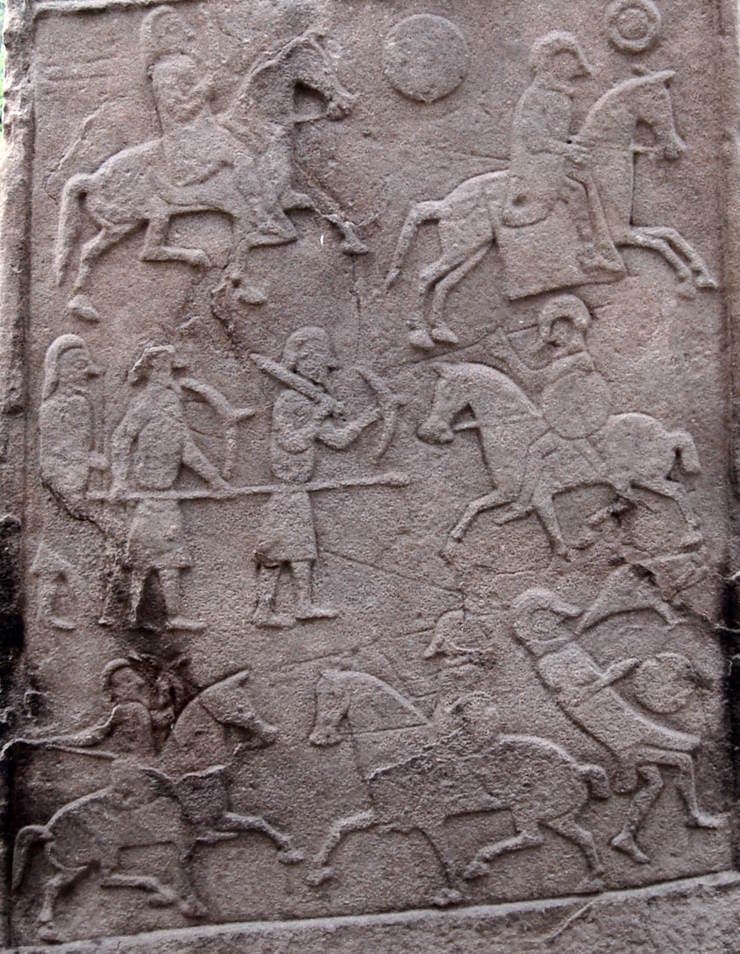

Bede does not tell us what Tondberht, Etheldreda’s first husband, felt about this situation, but Ecgfrith was clearly not happy – as a King, he would presumably have wanted an heir to the throne. He asked Bishop Wilfrid a number of times to intercede with Etheldreda, to persuade her to consummate the marriage, but she consistently refused and begged to be allowed to become a nun. Eventually, after twelve years of marriage, Ecgfrith agreed to let her go, and she entered the monastery of Coldingham. This allowed Ecgfrith to remarry, which he did. He died in battle, fighting the Picts, in 685.

A year after she had taken the veil at Coldingham, Etheldreda returned to her home in the Kingdom of the East Angles and founded her own monastery at Ely, where she became Abbess and was famed for her ascetic lifestyle. Etheldreda’s foundation was a double monastery, housing both men and women, which was the practice of the Anglo-Saxon church up to 787, when the Second Council of Nicaea banned mixed foundations.

Etheldreda died in 679, from a tumour in her neck – which she is said to have regarded as a divine punishment for her earlier fondness for necklaces. Her sister Seaxburh, widow of King Eorcenberht of Kent, succeeded her as Abbess of Ely. Etheldreda had insisted on being buried in a simple wooden coffin, but sixteen years after her death, Seaxburh decided to move her body to a more impressive tomb within the Abbey church. On exhumation, her body was discovered to be incorrupt, a sure sign of sainthood.

In the medieval period, Etheldreda’s shrine at Ely became an important centre of pilgrimage. As stories of cures and miracles at the site of her tomb spread, Etheldreda’s reputation grew; by the 14th century, she was known and revered throughout western Europe.

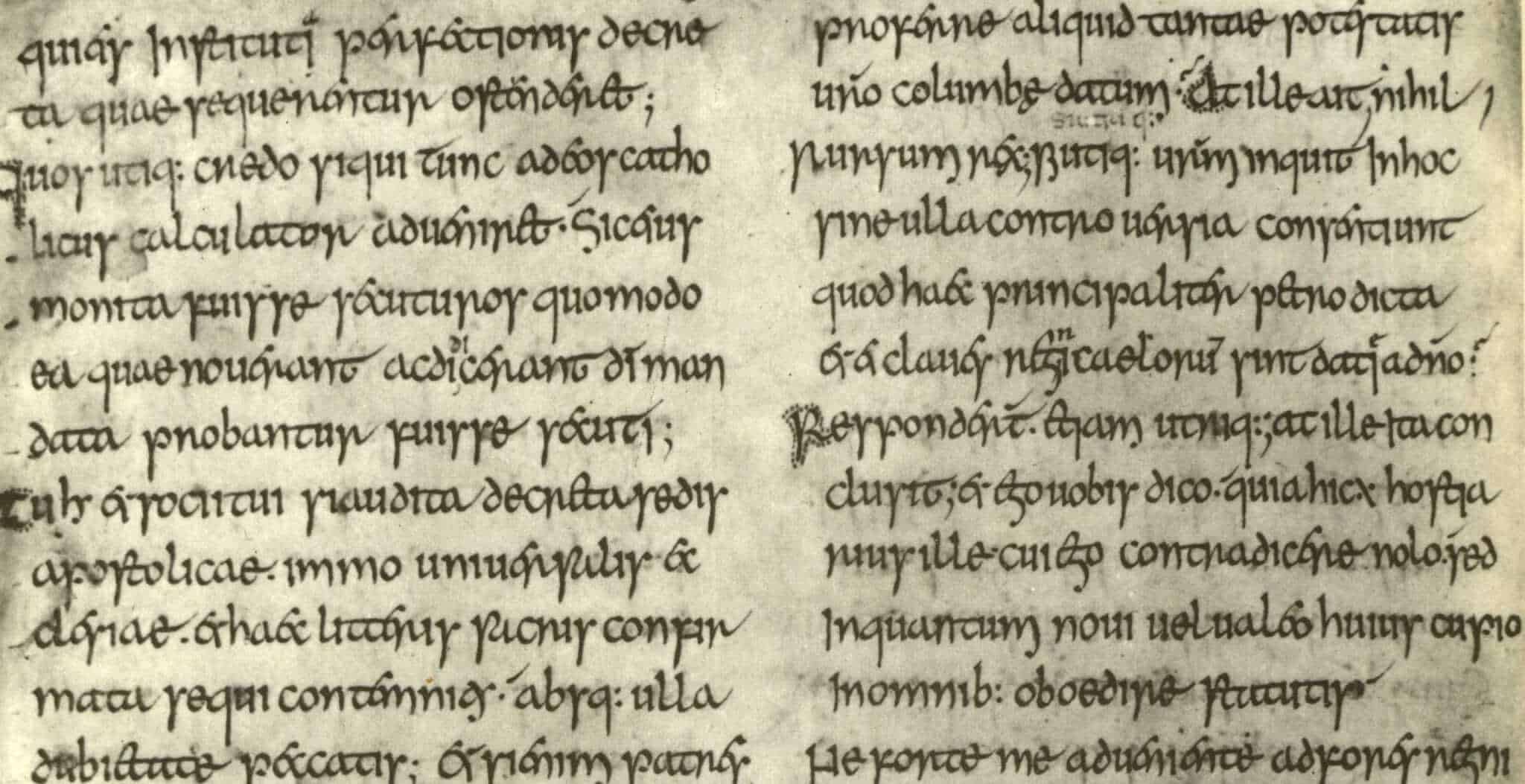

By this time, Bede’s brief biography of Etheldreda had been expanded by later writers, most importantly in the Liber Eliensis, a 12th-century chronicle of the monastery and Isle of Ely – now available in an English translation by Janet Fairweather (Boydell Press, 2005).

The Liber was written by a monk of Ely, which was by now an exclusively male Benedictine monastery. His chronicle recounts stories and traditions that had grown up around Etheldreda in the four centuries since Bede’s History. These include an exciting account of Ecgfrith’s supposed pursuit of Etheldreda as she journeyed south from Coldingham to Ely, and the miracles that accompanied her on the way. Several of these miracles – such as leaves sprouting from a staff, and water springing from rocks – recall Old Testament stories, and can be found in the Lives of other saints.

A number of the stories about Etheldreda that appear in the Liber seem to have been written with more than one purpose. They bolster her reputation as a powerful and holy woman, but at the same time they serve to further the interests of the medieval monastery.

One of the themes running through the Liber is the justification of the monastery’s claims to ownership of its lands, especially the Isle of Ely. The author refers a number of times to a story that Tondberht, Etheldreda’s first husband, gave her the Isle as a wedding gift. This is not necessarily untrue, although the story clearly has a practical function in the Liber, where it is invariably linked in the text with assertions that absolute ownership of the Isle had passed directly from Etheldreda to the medieval monastery.

Etheldreda was also portrayed by the author of the Liber as the protector of the monastery, a warrior saint who would defend its interests and punish its enemies. This occasionally took the form of actual violence against offenders: in the late 11th century, a man called Gervase, one of the administrators of the Norman sheriff of Cambridge, who was hostile to the monastery, took legal proceedings against the Abbot. The Liber recounts that, before the case could take place, Gervase was visited by Etheldreda and her sisters, Wihtburh and Seaxburh, who rebuked him and then ‘wounded him with the hard points of their staves’ – that is, their abbesses’ staffs. The servants heard his screams, and the unfortunate man lived long enough to tell them he had been attacked by the saints, before dying of his wounds.

The monastery of Ely was dissolved at the Reformation in 1539, and its shrines destroyed. Etheldreda’s reputation suffered an eclipse in the following centuries, which lasted until the revival of interest in the saints in the late nineteenth century, sparked by the rise of the Anglo-Catholic movement and a lessening of hostility towards Catholicism within the established Church.

The Church of England’s calendar celebrates Etheldreda on two feast days: 23rd June (her death) and 17th October (when her body was moved, and found to be incorrupt). A relic, believed to be the saint’s hand, is displayed in Ely’s Catholic church which bears her name. This year 2023, the cathedral is marking the 1,350th anniversary of the foundation of Saint Etheldreda’s monastery with a special programme of events, concerts, exhibitions and services.

Elaine Thornton is a writer and the author of a recent biography of the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Giacomo Meyerbeer and his Family: Between Two Worlds (Vallentine Mitchell. 2021). She is also a volunteer guide at Ely Cathedral.

Published: 17th March 2023