“The most learned man anywhere to be found”.

This bold statement from Einhard, the Frankish scholar and courtier to Charlemagne is a touching assessment of Alcuin of York’s reach academically, spiritually and culturally.

Alcuin was an English clergyman and scholar, who became a leading member of the Carolingian Court and a prominent figure in the subsequent Renaissance which emerged.

Born around 732 in Northumbria, not much is known about Alcuin’s family or background. As a child he was sent to the cathedral school in York under the tutelage of Ecgbert, who had benefited from a great education under the famous historian, the Venerable Bede.

The Archbishop Ecgbert and his brother, the Northumbrian King Eadberht, were both prominent figures in the English church at this time, following in Bede’s footsteps: many reforms would take place under their watchful eye. Moreover, Ecgbert would oversee young Alcuin’s education, watching him excel in such a stimulating environment.

Alcuin’s education was classical and he quickly showed himself to be a fast learner with a good memory. He also benefited from being surrounded by esteemed scholars such as Ethelbert, the man who succeeded Ecgbert as Archbishop of York in 766.

Ethelbert would be an important influence on Alcuin, not only as a teacher but a friend. Ethelbert was a vital figure in the community and helped to rebuild the Church as well as send missionaries to the Continent.

With fellow scholars, Alcuin would embark on visits to the continent in order to acquire books and artworks for the library at York which at the time was one of the greatest in this part of the world. Contained within the library walls were some of the classic literary greats such as Cicero and Virgil.

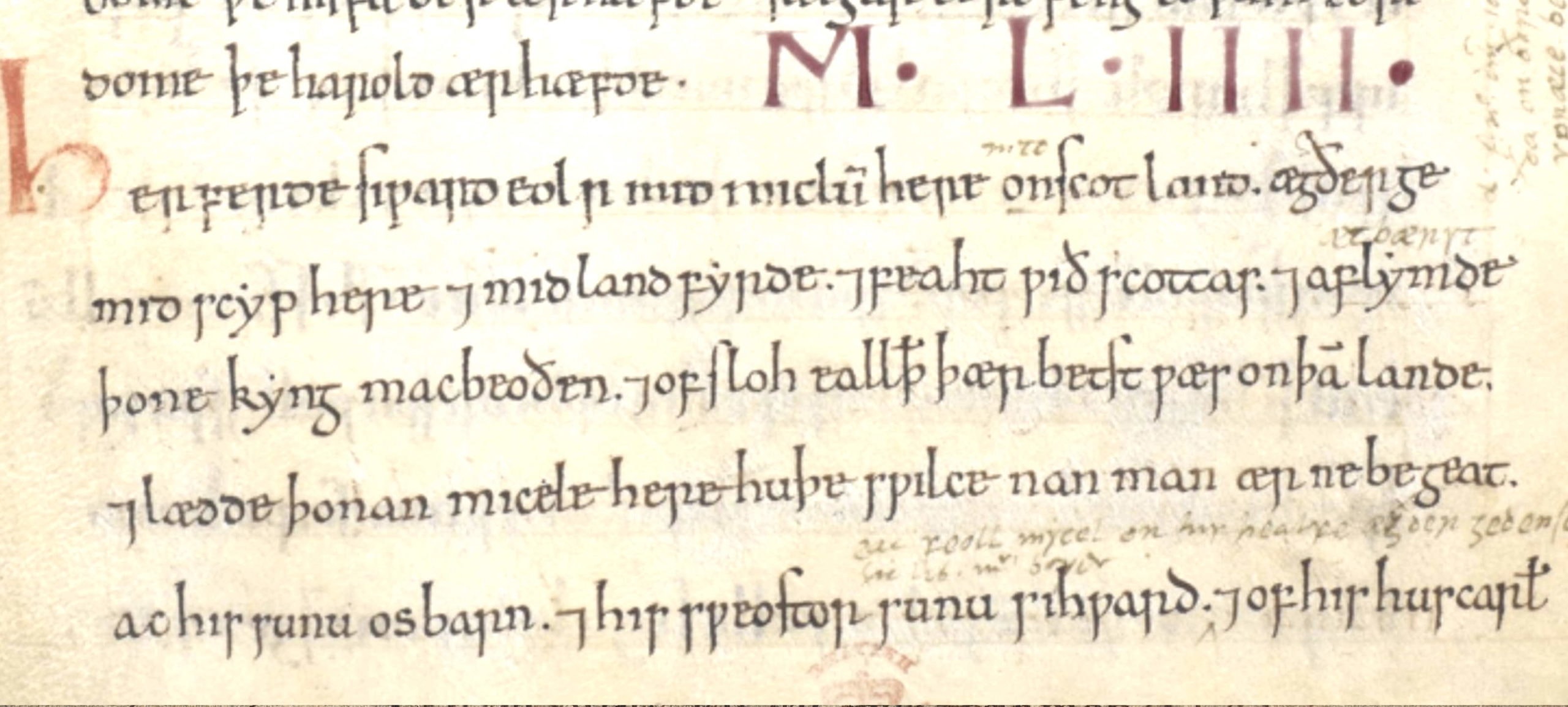

The library became well-known, however sadly in 866 it came under attack from marauding Vikings and was destroyed.

Fortunately, Alcuin’s own literature survived, providing a key source for the period as he composed poetry inspired by his surroundings in York and dedicated to the saints and prelates of the church.

Although never becoming a priest, he was a life-long deacon and by the time he was thirty he had made the transition from student of the school to teacher and eventually, master.

The school was celebrated not only for its religious instruction but also as a dynamic cultural centre for learning. Such an academic background would leave an indelible influence on Alcuin as he embarked on his teaching career and travelled to the continent.

Whilst teaching in York, Alcuin and the Archbishop of York travelled to Rome in the 760s. Such trips would continue for the next couple of decades including when he was sent on what would be the first of many missions to the court of Charlemagne.

Charles the Great, Charlemagne or the “Father of Europe” as he was also known, was King of the Franks in 768. A decade later he would become King of the Lombards, then Emperor of the Romans in 800.

He was arguably one of the most significant and defining figures of early modern Europe. Represented as a unifying force in Western Europe, he expanded his Frankish territory to become the Carolingian Empire.

This in turn ignited a time of great culture, learning and intellectual prosperity referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance. It was great phenomenon which Alcuin would find himself the centre of in the coming decade.

In 781 King Elfwald sent Alcuin on yet another mission, this time to Rome in order to confirm the appointment of the new Archbishop of York, Eanbald I as well as to petition the Pope for York’s formal confirmation as an Archbishopric.

This was a trip that would set Alcuin on course for a great rise in prominence, status and influence. On his way back from Rome he called in to Charlemagne’s court at Parma, only to receive an invitation by the king himself to join his court as a scholar.

Such a great offer could not be refused and Alcuin was soon on his way to join a group of likeminded intellectuals of the day, selected by Charlemagne from across Europe, gathered to form a scholastic union in his court at Aachen.

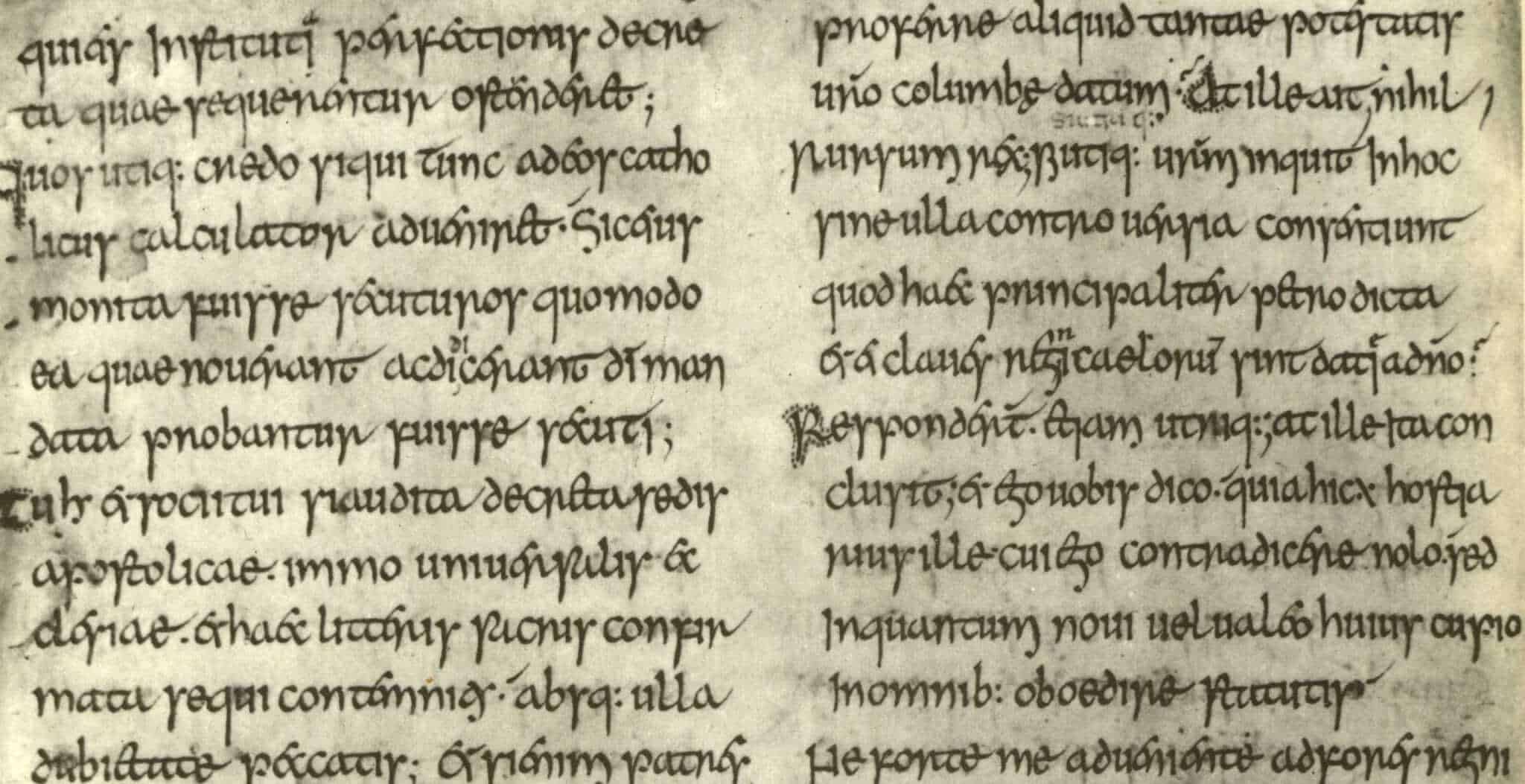

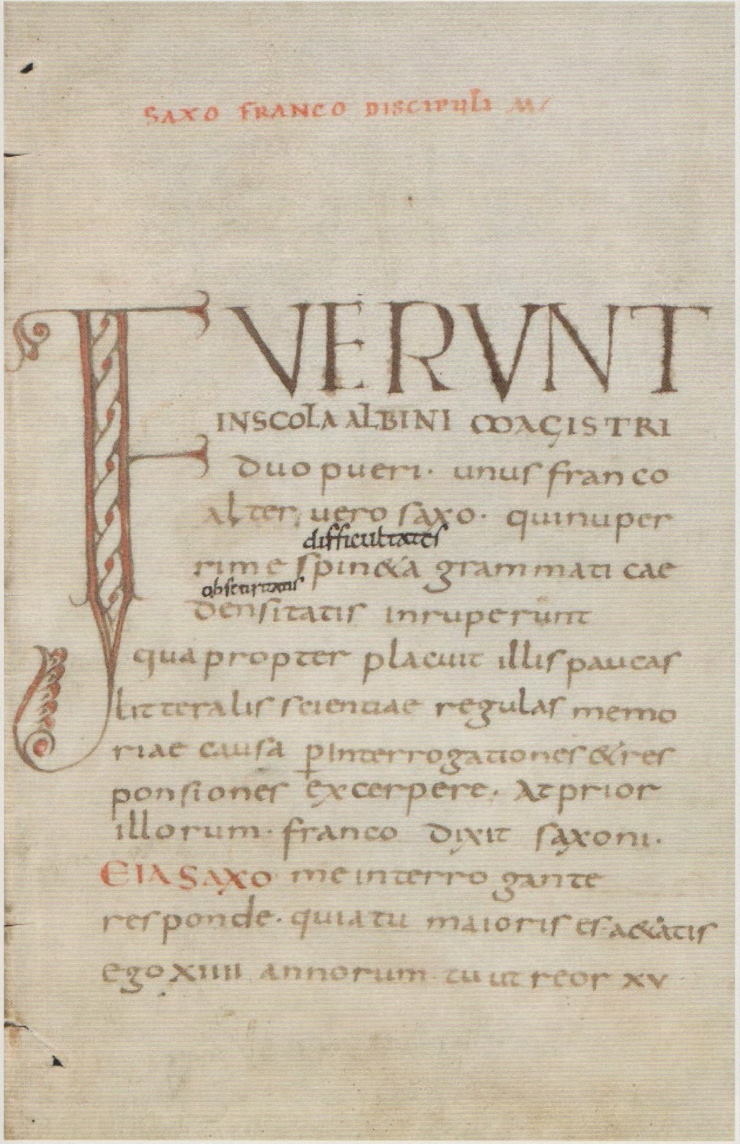

Alcuin would prove himself to be a great scholar as well as important teacher who wrote poetry, letters and grammatical instructions as well as theological treatises.

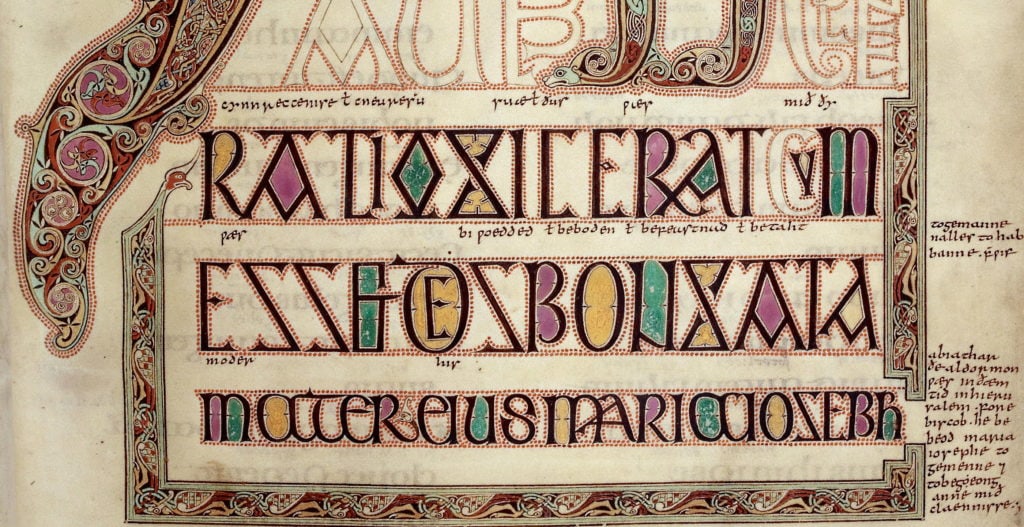

He also proved himself to be vital in the development of the Carolingian minuscule which had originated with Benedictine monks in 778 and was subsequently advanced. The script would continue to evolve over the next three centuries and was vital in providing a standardised calligraphy in early medieval Europe.

Alcuin’s input in this literary development was to provide copies and preserve the script through manuscripts of both educational and religious importance.

One of his greatest contributions was the Golden Gospels, a breathtaking illuminated manuscript written in gold on purple vellum. Charlemagne’s court at the time was dedicated to intellectual and religious splendour, recreating the Roman artistic style in all its glory.

Alcuin’s many roles in court included serving as English ambassador. He provided an important link between the continent and England, allowing an exchange of ideas and open lines of communication.

Moreover, one of his principal roles was as a teacher and he was soon made head of the palace school based in Aachen, which had some notable pupils of great social standing. Inspired by his time at York, he composed a curriculum at the Frankish school based around the seven liberal arts of trivium and quadrivium, consisting of grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, astronomy, music and geometry.

This tradition of learning was rooted in Ancient Greece but adopted in the Middle Ages, thus having an important impact on the subsequent Carolingian Renaissance which emerged out of Charlemagne’s court. Many of Alcuin’s students would become important contributors to the intellectual Renaissance.

Many of the ideas discussed within the court found themselves in Alcuin’s correspondence to Charlemagne, to other members of the court and those he maintained contact with back in England.

His letters express his interest in a range of pressing theological and social issues of the day. In total, he left behind around 300 Latin letters which are invaluable as a source for this early medieval period.

In one particular correspondence he discusses his discovery of the sad fate of Lindisfarne’s status as a cultural and religious sanctuary, altered forever by the Viking raid in 793.

He expressed his great sorrow and analysed the event as God’s punishment for the behaviour of the people of Northumbria.

Alcuin’s letters provide a great window into the era, reflecting personal tribulations as well as referencing some of the larger events occurring at the time which changed the landscape in England as well as further afield.

In 790, Alcuin made a return to England, however the trip was cut short when he was called upon by Charlemagne to help in the fight against adoptionism heresy, the belief that Jesus was adopted as the son of God. As these sentiments were becoming prevalent in Toledo, Spain, Alcuin would use his contacts with Beatus of Liébana from Asturias to fight this heresy. He returned to the Carolingian court and sadly never set foot in England again.

By the summer of 796, after achieving great strides at Charlemagne’s school, Alcuin became abbot of St Martin’s monastery at Tours. This was an important monastery where he would go on to establish a school as well as a library. This would be the location in which he composed many of his letters and most notable literary works, including the continued work of the precious Carolingian minuscule script. It would also be the place where he would end his days, passing away in May 804.

Alcuin was a notable scholar and teacher as well as religious leader who left behind a great intellectual and cultural legacy. His impact on others and his introduction of new standards of education and learning helped to revive the pursuit of intellectual excellence in the Carolingian Empire and beyond.

He is remembered as a man of great significance who raised standards and made reforms in religion, literature, scholarship and learning, defining a period of European history and providing a looking glass into a medieval world we still know so little about.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: June 25th, 2021.