January 28th, 1896 must have started out as an ordinary day for the police constable responsible for Paddock Wood, Kent. As he pushed his bicycle through the quiet streets, he probably had nothing more on his mind than wondering whether today was the day he’d be able to say “You’re nicked, son” to that rogue of a poacher.

While proceeding in an orderly fashion through the village, the peace of the constable’s regular beat was suddenly and rudely shattered. He wasn’t to know that what was happening was also an event of national, and, ultimately, international significance.

Belting past the bobby at a scary 8mph, a motorist by the name of Walter Arnold was about to enter the record books in a burst of exhaust fumes and a flurry of legal activity. Not only was he clearly breaking the speed limit for one of these infernal machines, which was 2mph, but also, and even more damningly, he had no man with a red flag preceding him as the law required.

The bobby on the beat set off in hot pursuit on his regulation issue bicycle, finally catching up with this deranged road racer after five miles. Having captured his man, what was a bobby to do in pre-speeding ticket days? It’s not hard to imagine a subsequent scene between motorist and constable.

“Gasp – didn’t you hear me shouting at you to pull over sir? – cough – must ask you to accompany me – hang on a minute – wheeze…“

“Have you thought of asking your superiors for an upgrade, constable? I could provide them with a very good deal on a Benz motor, finest German engineering…”

“Now I’ve got my breath back, I’m writing you a citation, sir.”

Walter Arnold was no ordinary motorist. He was also one of the earliest car dealers in the country and the local supplier for Benz vehicles. He was well ahead of the times and set up his own car company producing “Arnold” motor carriages at the same time. It has to be said that the subsequent publicity surrounding his speeding offence probably wasn’t entirely unwelcome, and it was certainly a game changer for the automobile.

The London Daily News detailed the four counts, also known as “informations”, on which Walter Arnold faced charges at Tunbridge Wells court. Arnold’s vehicle was described several times in the newspaper court report as a “horseless carriage”, and the case clearly raised some interesting philosophical as well as legal points for the bench.

The first count, which reads oddly now, was for using a “locomotive without a horse,” the next for having fewer than three persons “in charge of the same”, indicating the enduring influence of horse-drawn and steam locomotion when it came to legislating the new vehicles. Next came the actual speeding charge, for driving at more than two miles per hour, and finally, a charge for not having his name and address on the vehicle.

In defence, Arnold’s barrister stated that the existing locomotive acts had not foreseen this type of vehicle, throwing in the names of a couple of elite users, Sir David Salmons and the Hon. Evelyn Ellis, who had never had any problems while out and about in theirs. Whether this was intended to impress the court or to make some point about one law for the rich and another for the man in the street is not entirely clear.

Since this was a case that would set a precedent, referencing names of people who were in the public eye would avoid the problem that has become a by-word for judges who are out of touch – the “who he?” reaction. The origin of this phrase, frequently referenced by satirical magazine Private Eye, lies in the response of one judge in the 1960s who was heard to ask in court “Who are the Beatles?”

Mr Cripps, defending, said that if the Bench considered the vehicle was a locomotive, therefore presumably legislating it within existing acts, they should charge a nominal fine. Eventually, Mr Arnold was fined 5 shillings for the first count of “using a carriage without a locomotive horse” (aka “horseless carriage”) plus £2.0s.11d costs. On each of the other counts, he was to pay 1 shilling fine and 9 shillings costs. Effectively then, his speeding offence cost him a shilling. All in all, the publicity it created may have made it worth it.

The case may have had an influence on the changes to legislation shortly afterwards. The man with the red flag was no longer required, presumably leading to labour exchange staff scratching their heads over what to do with a skill that clearly wasn’t that transferable. The fearsome machines no longer needed a minimum of three people to control them (“Whoa car, ah said whoa, whoa!” to paraphrase cartoon character Yosemite Sam).

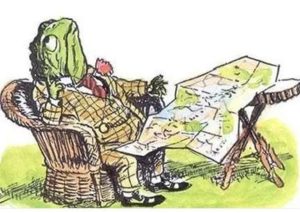

There’s more than a touch of one famous literary character about Mr Arnold, whose love of speeding seems to match that of Kenneth Grahame’s Mr Toad in ‘The Wind in the Willows’: “‘Glorious, stirring sight!’ murmured Toad. ‘The poetry of motion! The real way to travel! The only way to travel! Here today – in next week tomorrow! Villages skipped, towns and cities jumped – always somebody else’s horizon. O bliss! O poop-poop! O my! O my!’”

Unlike Toad, however, who ended up in “the remotest dungeon of the best-guarded keep of the stoutest castle in all the length and breadth of Merry England”, his sentence extended for “gross impertinence to the rural police”, Arnold sped off into a glorious new dawn. The speed limit now rose to a breathtaking 14mph, and drivers throughout the land, including Walter Arnold in his Arnold Benz, celebrated with the Emancipation Run from London to Brighton.

Arnold’s beautiful little vehicle took centre stage at the Hampton Court Concours of Elegance in 2017. Clearly showing the ancestry of horse-drawn vehicles in its design, with carriage lamps on either side and a coachman style bench with footboard, it is an important part of our past, telling us so much about one of the most significant transitional periods of human history.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.