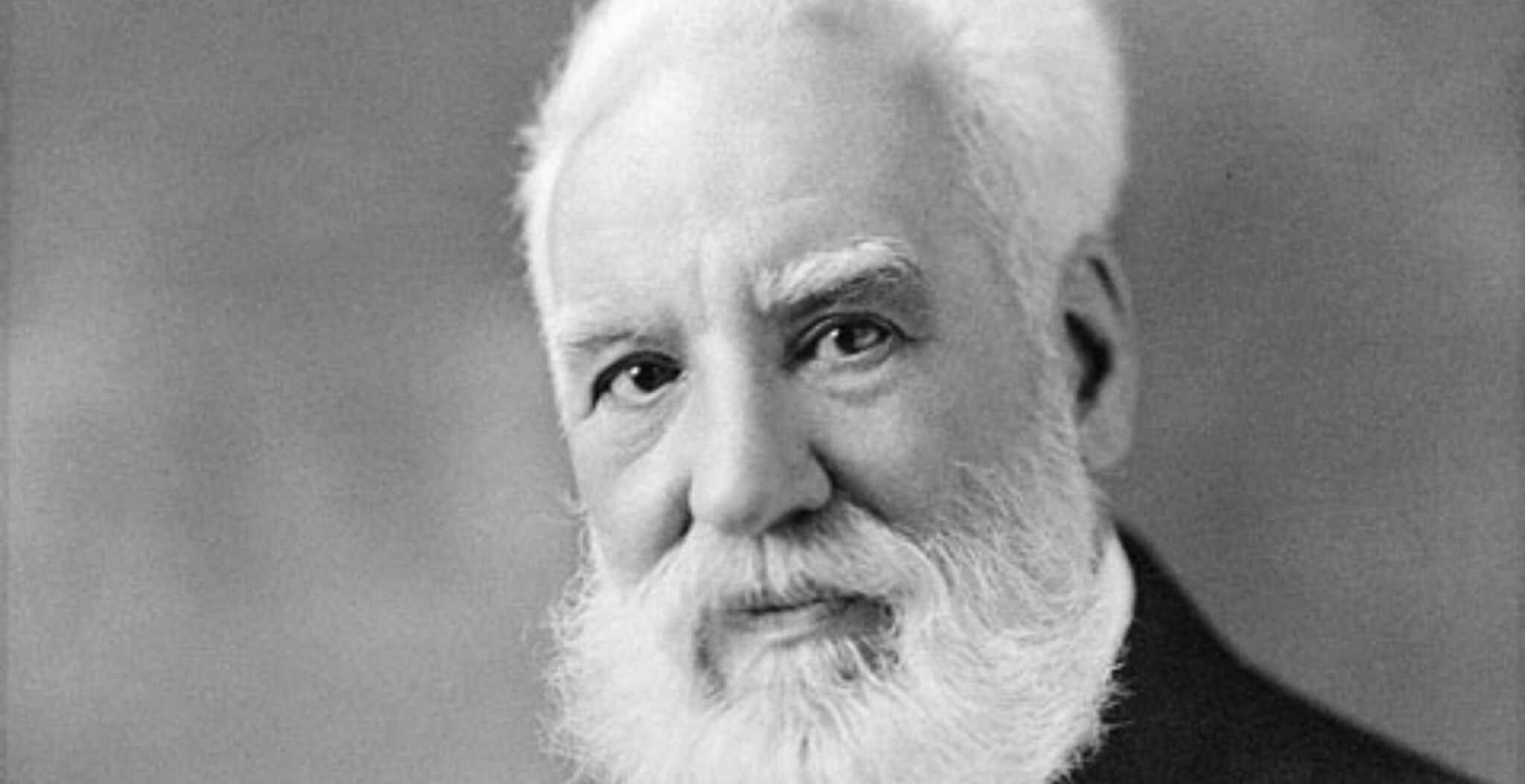

Largely forgotten in his own country, Frank Whittle was indeed the true inventor of the jet engine, the invention that would go on to revolutionise aviation and the mode of travel for future generations to come. Frank was the working-class hero, who could well have spared his country much of the devastation of World War II if only the British Establishment had been quicker to listen to him.

Frank was born in the Earlsdon area of Coventry on 1st June 1907, the eldest son of Moses Whittle and Sara Alice Garlick. The family later moved to the nearby town of Royal Leamington Spa after Frank’s father purchased a small engineering company. It was here where Frank was allowed to get his hands dirty honing his practical engineering skills whilst helping in his father’s workshop.

An enthusiastic reader, Frank spent much of his spare time in the Leamington reference library, reading about astronomy, engineering, turbines and the theory of flight. His boyhood heroes were indeed the brave aces of the Royal Flying Corps from World War I.

At the age of 15, determined to be a pilot, Whittle applied to join the Royal Air Force’s apprentice school at RAF Cranwell. Frank made such an impression on the powers that be, that he was one of only a handful to be selected for the officer training college next door. And it was here that he would go on to prove himself as both an excellent pilot and engineer.

When not flying, Frank was busy writing a thesis that proposed that if aircraft were to fly faster, they could only achieve this if they were able to operate at much higher altitudes where the air was thinner. He concluded that the conventional propellor driven by a piston engine was not the answer and that a new sort of engine would be required. His thesis received top marks – even though the professor who marked it even admitted that he did not fully understand it.

His ‘Eureka’ moment came out of the blue when he proposed using a gas turbine to blow air out of a high-powered exhaust pipe at the rear as a means of propulsion for the aircraft. Frank had effectively dreamed up the turbo-jet – the early jet engine.

But when the young RAF officer took his brainchild to the Air Ministry in 1929, their boffins scrutinised it but ultimately rejected it and continued to order conventional aircraft with propellors.

Undeterred, Frank applied for and was subsequently granted a patent to protect his turbojet. The patent was duly published and received much interest from some German diplomats in London. When the patent expired in 1935, Frank was not even able to afford the £5 renewal fee. Not that that would have made very much difference, as his plans were now being widely circulated amongst many German aviation engineers. The invention that may well have influenced or even stopped the war was now common knowledge.

Back in England however, Frank did receive some backing from the RAF as they supported him through Cambridge University where, needless to say, he graduated with a First Class honours degree in Mechanical Sciences. During his time at Cambridge Frank continued the design work on his new jet engine.

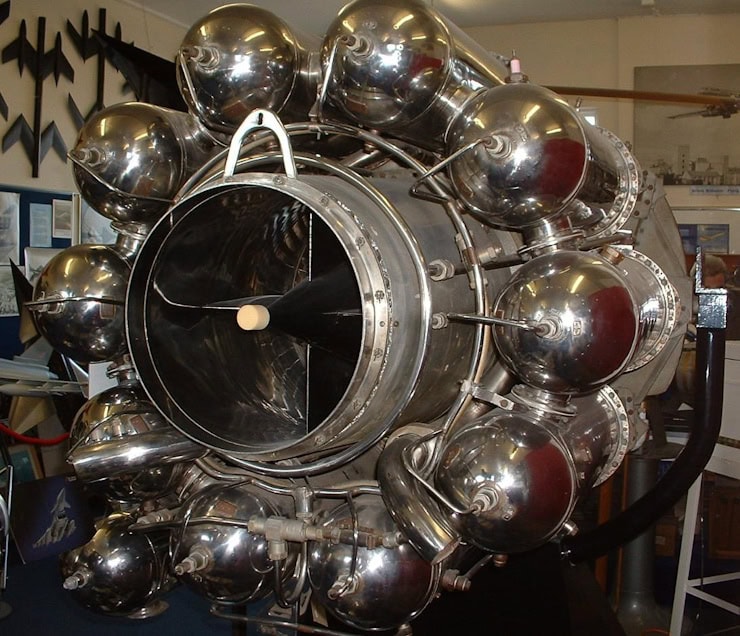

Finally, Frank, along with two of his friends, secured sufficient funding to found the company Power Jets Ltd and in April 1937, demonstrated his experimental jet engine for the first time.

In 1941, a Gloster E28 aircraft took to the skies of Britain powered by a Whittle jet engine – some 12 years after his idea had been rejected by the Air Ministry, by which time the Germans had already powered ahead, equipped with Frank’s patent and backed by Nazi funding, in 1939 their first jet aircraft, designed by Hans von Ohain, had taken to the skies. Although the engine was severely limited in its range and reliability, history had already been made.

Back in Britain, Power Jets were suffering a major conflict of interests with their business partners at the Rover Company concerning the design of Frank’s new jet engines, and consequently relationships broke down in favour of Rolls-Royce. Backed by the Ministry of Aircraft Production, jet engine manufacturing was consolidated at the Rolls-Royce factory at Barnoldswick in Yorkshire, where developments moved at a much faster pace. Engine testing increased dramatically with improvements being made on an almost daily basis.

Following a demonstration of the E.28 aircraft to Winston Churchill in April 1943, Frank proposed to Stafford Cripps, Minister of Aircraft Production, that all jet development be nationalised. The government finally conceded, nationalising Power Jets in 1944.

With the USA and Russia now in the war, a government decision was made to share all of Frank’s research with Britain’s allies. The Rolls-Royce Nene engine was licensed and made in two different countries: in the United States by Pratt & Whitney and also in the USSR. Subsequent developments from these early jet engines would power the aircraft that would confront each other in dog fights during the Korean War of the early 1950s.

Suffering from nervous exhaustion, Frank retired from the RAF in 1948, leaving with the rank of air commodore. In recognition of his service, he was awarded a knighthood as well as a tax free thank you of £100,000. He embarked on a career as a consultant in the new and burgeoning jet engine industry that he had indeed created.

Winning countless awards for his distinguished contributions to commercial aviation, in 1977 Frank emigrated to the US, later accepting the position of Research Professor at the United States Naval Academy.

Frank died of lung cancer on 9 August 1996, at his home in Columbia, Maryland. Cremated in America, his ashes were returned to England where they were placed in a memorial in a church in Cranwell, Lincolnshire.

History is of course full of ‘what-if’s’ and of course we will never know the answer, however the question has to asked: if Britain had taken young Frank’s turbojet idea more seriously in 1929, then would we have had a jet fighter that could have blown anything the German Luftwaffe could throw at us out of the skies?

In a conversation with Frank after the war, the German engineer Hans von Ohain is said to have stated: “If you had been given the money, you would have been six years ahead of us. If Hitler or Goering had heard that there is a man in England who flies 500 mph in a small experimental plane and that it is coming into development, it is likely that World War II would not have come into being.”

By Trevor Alan.

Published: 2nd February 2026