In war, national leaders propose strategies and aims and argue over the means to carry them out. However, it is the frontline officers who turn the strategies into action and they and the frontline soldiers who carry those strategies through.

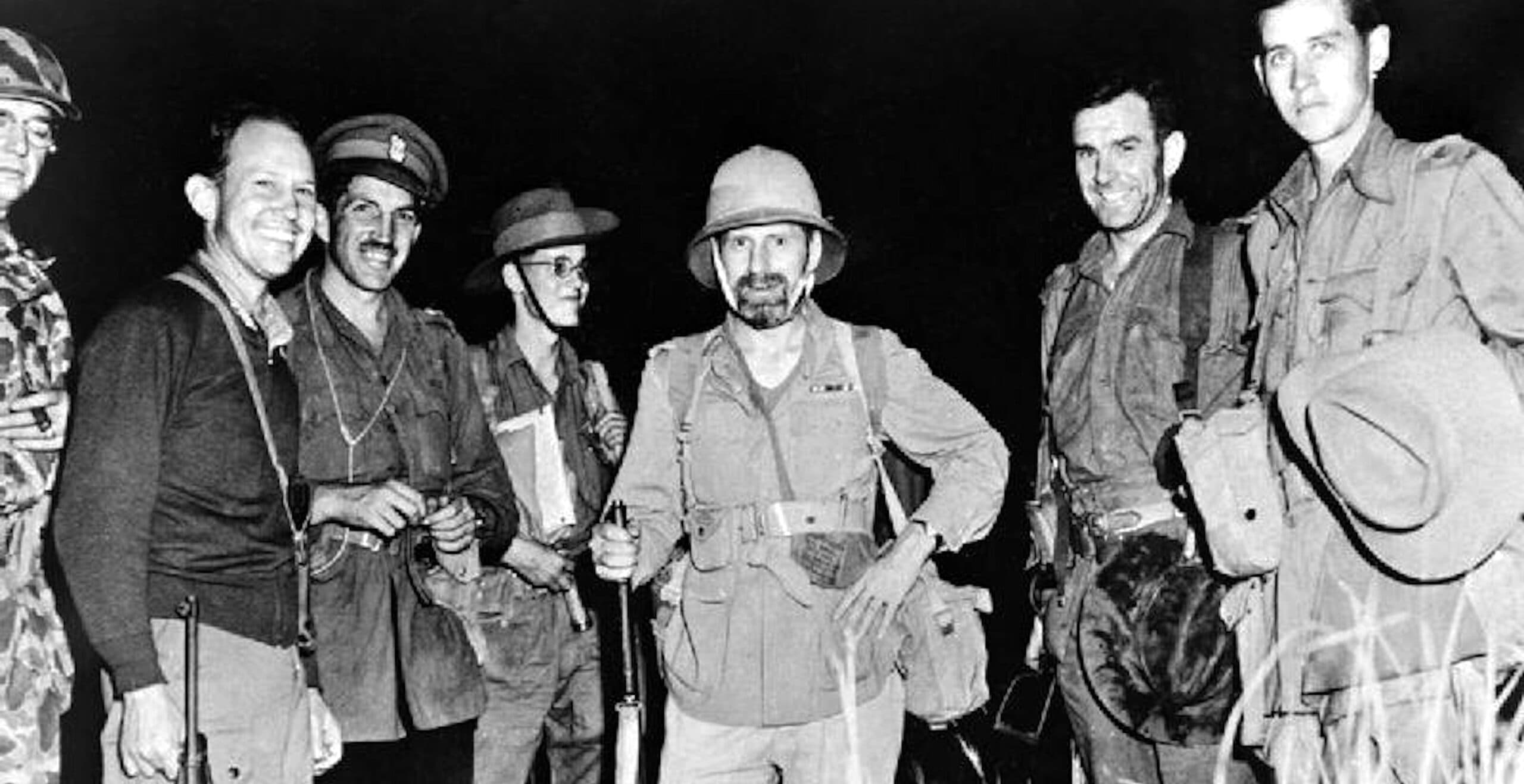

To implement their plans, the strategists of war have always made use of unconventional characters, such as bagpipe playing, bow-wielding Jack Churchill, and T.E. Lawrence in his burnous and Rolls Royce. Then there was Major Vladimir Peniakoff, commander of the British Army’s No. 1 Demolition Squadron, PPA (better known as Popski’s Private Army). One of the most controversial of all the eccentric individuals of the Second World War was Major-General Orde Wingate, leader of the Chindits during the Burma Campaign.

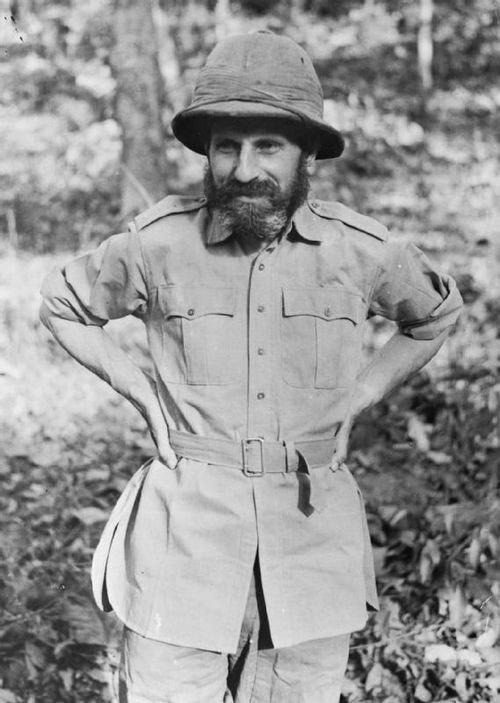

The Chindits were a British special operations force tasked with conducting long-range raids deep behind Japanese lines in Burma. Officially known as Long Range Penetration Groups, their nickname came from the Chinthé, a Burmese temple guardian figure known as the “fabulous lion” in English. “Chindit” appears to have been a coining created by Wingate, perhaps based on his own attempt to say it. The Chindits embodied the hallmarks of their leader Orde Wingate: bold innovation, extreme endurance, and unorthodox and ruthless tactics.

Born in 1903 in British India, Orde Wingate’s family was deeply religious. His Christian upbringing shaped his strong convictions and uncompromising approach to warfare. He learned to stand up for himself at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, and by the time he was 22, was on his way to a career as an officer. He soon gained a reputation for being argumentative and even insufferable. They were tags that would follow him through life and it’s not surprising, given his track record. He was a hard-riding, tough-living individual, continually testing his own powers of endurance. His fellow officers in the Army School of Equitation detested him. Wingate was never a popularity-seeker and this probably did not bother him in the least.

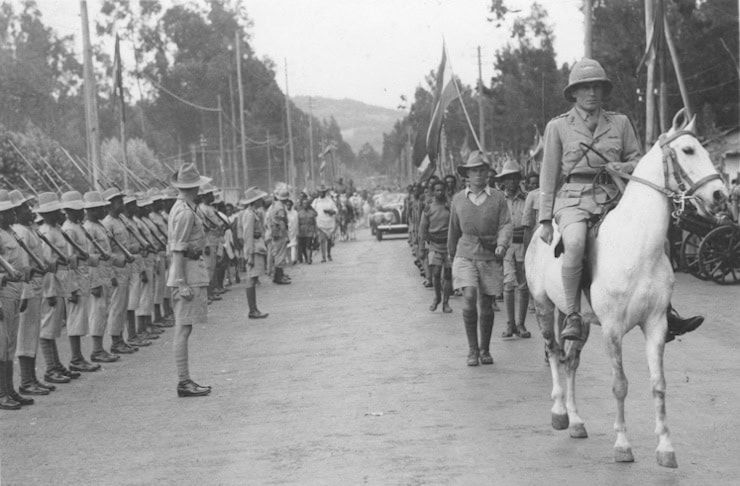

On his way to join the Sudan Defence Force in 1927, Wingate cycled across Europe before taking a boat to Cairo. Then he went on to Khartoum where his papers for the SDF were served. The SDF patrolled against slavers and poachers, and during this period Wingate honed his ambushing techniques. Later, In Ethiopia, Wingate and his Gideon Force (named after the Biblical judge greatly admired by Wingate) were hailed liberators by the population, having freed them from Italian colonialism during the early part of the Second World War.

Wingate served most controversially in Palestine in the 1930s, where, with the support of Archibald Wavell, Commander of British forces in Palestine, he organised the Special Night Squads. These were joint British-Jewish forces that conducted operations against Arab militants. His tactics were violent, ruthless, and effective, earning him both admiration and controversy that lasts to this day. He became a Christian Zionist. His strong support for Zionism and the creation of the Special Night Squads contributed to his enduring reputation in Israel.

For some a hero, for others little more than a violent thug, Wingate’s contact with Wavell and others high in Britain’s military command nonetheless stood him in good stead in the Second World War. Now experienced in controversial and unorthodox tactics, he convinced British high command that small, highly trained units could operate deep in enemy-held territory and disrupt lines of communication. In 1942, Wingate was given permission to form the Chindits as an experimental force trained for prolonged jungle warfare. They operated behind Japanese lines, disrupting supply routes and forcing the enemy into exhausting jungle battles.

Wingate’s leadership style was intense, to say the least. He demanded absolute loyalty and pushed his men to their limits. He was known for his eccentric habits, including eating raw onions (a habit that was also shared by “Father of Archaeology” William Flinders Petrie) and quoting the Bible in military briefings. His ideas influenced modern special forces tactics, but his methods were considered dubious. He spared little to no thought for those he fought against, and his own units also suffered, resulting in high casualty rates among his troops.

Wavell agreed to give Orde control of the Indian 77th Infantry Brigade, which Wingate transformed into the Chindits. The Chindit units were half British, and half composed from the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Rifles and the 2nd Battalion Burma Rifles. To become a Chindit, every man underwent a rigorous training that included jungle survival skills, the application of supply tactics based on airdrops for food and ammunition, and a type of hit-and-run combat including ambushes, sabotage, and continual psychological disruption of the enemy. Even during training Wingate pushed his men hard, making them camp out in the jungle during rainy season, resulting in many becoming ill.

The Chindits were involved in two main campaigns in Burma. The first was Operation Longcloth in 1943, which trialled the various techniques and tactics Wingate had developed. A 3,000 strong force of Chindits crossed the Chindwin River and infiltrated Japanese territory, aiming to destroy infrastructure by disrupting railway lines and supply routes. However, logistical issues and the hostile terrain led to heavy casualties, conditions which were exacerbated by Wingate constantly changing his plans. Of the original force, only a fraction returned. Despite this, the operation proved that deep penetration warfare was possible, if at great cost, laying the foundation for future missions. The success also had a positive effect on the morale of other troops of the British Army.

Wingate’s report of the action included severe criticisms of fellow officers while playing up his own role. Nonetheless, he managed to impress Winston Churchill and they both attended the Quebec Conference, where Wingate gained support, particularly from the USA. This resulted in further resources to help him carry out a second campaign. His force was expanded, although other British commanders were opposed to it. He was given further units to make another brigade, including the 3rd West African Infantry Brigade. He was also provided with the support of the 1st Air Commando Group, which consisted mainly of USAAF aircraft, thereby gaining access also to the better quality American ration packs for his units.

Operation Thursday in 1944 was Wingate’s most ambitious action. It involved airborne as well as ground infiltration. The Chindit units were flown into enemy territory where they established fortified bases. The goal was to support larger Allied advances and to halt Japanese movement. The Chindits fought fiercely, resisting counterattacks and protecting airstrips. Wingate was killed in a plane crash during this campaign, when the USAAF B-25 carrying him on a flight to meet with air force officers hit a mountain during a thunderstorm. He was replaced by Brigadier Lentaigne, whose own experience and background were very different from those of Wingate.

Eventually, the Chindits were placed under the command of General Stillwell, an American supporter of Wingate. Many of the troops lost huge amounts of weight in action – up to a third of their bodyweight – and after the war “Chindit Syndrome” was recognised. This condition resulted from a combination of diseases contracted in the jungle, such as malaria, dysentery and ulcerated sores that frequently became septic.

Although the Chindits suffered high casualties, many historians argue that their daring missions contributed significantly to the ultimate Allied victory in Burma. Their legacy persists in modern commando units, influencing jungle warfare techniques and airborne special operations. As Martin Sambrook, academic researcher of the Chindit phenomenon, argues, Wingate and his fighters created an archetype. This was the image of the jungle combatant fighting on the British side, a figure who became a mainstay of postwar comics for boys in the UK.

Wingate’s body was buried in Burma and then removed, along with others, to be reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery in the USA on November 10, 1950. Whatever his own reputation, the men who served as Chindits were fiercely proud of their contribution. They carried up to 80 lb of equipment on their backs through the jungle on foot, often through dry teak jungles where they could not even find enough water to sustain themselves. They died in their dozens from disease and were regularly killed and injured in ambushes.

In 2015, 77th Brigade was recreated by the British Ministry of Defence. Its role remains innovatory, including countering cyberattacks. The Brigade continues to use the Chindit “Fabulous Lion” as its emblem.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th April 2025.