The Burma Railway, also referred to as the Death Railway, has become a distinctive symbol of the Asian theatre of war, representing the brutal conditions endured by Allied prisoners of war and innocent civilians in the region, under the regime of Japanese occupation.

Constructed by captured POWs and abducted civilians, the railway was a 258 mile line connecting Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma (modern-day Myanmar). The rail link was built under atrocious conditions of forced labour, arduously long hours and back-breaking work, all of which was made even more difficult by the poor sanitation, malnutrition and rampant spread of disease.

The railway line itself was a necessary part of Japanese wartime infrastructure, facilitating the transfer of troops and supply of weapons for the Burma campaign. It also served as an extension of the existing rail link between Bangkok (Thailand) and Rangoon (Burma).

The Japanese war efforts had been going from strength to strength since it launched its surprise attack on the US Navy base at Pearl Harbour in December 1941. Numerous attacks soon followed on strategic locations across the Asia-Pacific region.

The invasion of the Malay Peninsula by the Imperial Japanese Army and the subsequent fall of Singapore saw a massive number of Allied soldiers fall into the hands of their enemy, amounting to around 130,000 POWs.

In June 1942, six months after the attack on Pearl Harbour, a decisive naval battle took place in the Pacific theatre: the Battle of Midway. This proved to be not only a decisive victory for the US Navy, but most importantly, it severely hampered the ability of the Japanese Navy to defend its supply route which was required for reinforcements and provisions for their campaign in Burma.

Thus, the Japanese were forced to rethink their supply lines and decided to create the Burma railway line in order to relieve its forces.

The railway construction itself was fraught with practical difficulties dictated primarily by its topography, which is characterised by rugged terrain and dense jungle. Moreover, it would require viaducts, embankments, cuttings and most importantly, up to 600 bridges.

The building work began on 16th September 1942 with the plan to have it completed by December 1943. In reality, the infrastructure project was completed ahead of schedule as a result of the forced labour of thousands of Allied POWs and abducted civilians.

The Japanese Army had workers moving up and down the railway line as required, facilitated by the construction of camps providing rudimentary housing for 1,000 workers, staggered every 5 to 10 miles along the route.

The barracks housed around 200 people, giving each individual a space of just two feet in which to sleep.

One of the most significant elements of construction was the building of bridges, with one in particular made famous by a film of the same name. The bridge over the River Kwai saw initially 1,000 prisoners begin work on the project in October 1942. A few months later, another 1,000 POWs arrived to assist in its construction. Workers included British and Dutch POWs as well as Chinese, Malay and Tamil civilians.

The workers on the railway line were taken from two sources by the Japanese. The largest group consisted of around 200,000 local people, with Allied POWs making up the rest.

The civilians, who had been abducted and forced into labour by the Japanese, included men, women and children. Ethnic groups included Tamils and Chinese from Malaya, Burmese, Thais, Javanese as well as other locals from the region. The 60,000 POWs who were forced to work included British, Australian and Dutch soldiers.

The forced labourers were monitored by around 12,000 Japanese soldiers (including some from Korea) whose main responsibility was as supervisors and guards.

Many accounts from survivors attest to a regime of cruelty involving violence, torture, neglect and routine punishments. This system of brutality only added to the misery and most importantly contributed to the high death rate.

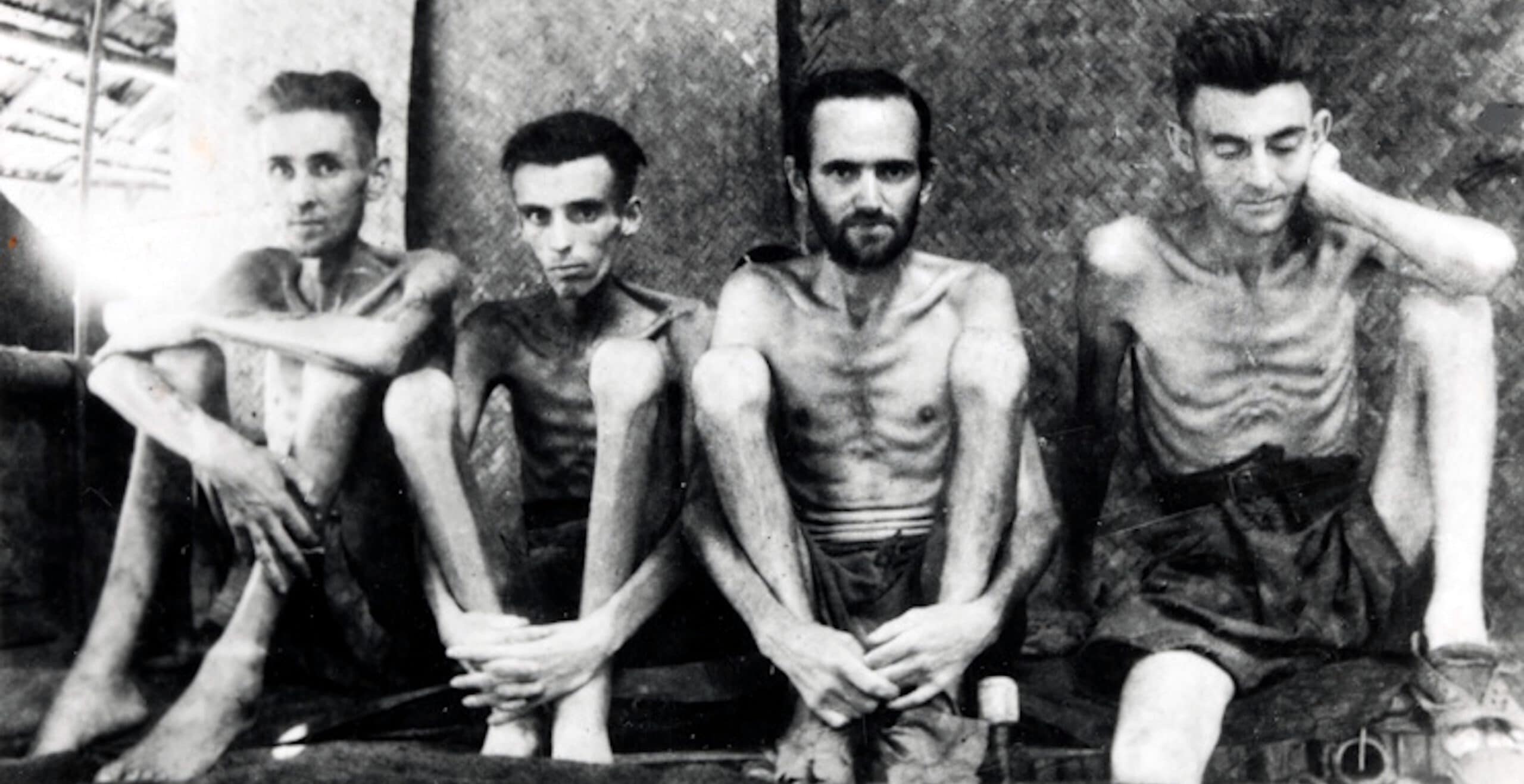

Sick and Dying- Cholera Lines – Thai-Burma Railway, 1943. A camp on the Thai-Burma Railway.

Sick and Dying- Cholera Lines – Thai-Burma Railway, 1943. A camp on the Thai-Burma Railway.

By the end of the construction around 90,000 civilians had died and another 12,000 Allied soldiers had perished as a result of the work and appalling environment.

That being said, conditions were so poor that not even the Japanese themselves were without fatalities: around 1,000 Japanese died during the construction of the railway line.

The Japanese had tried to attract local workers to the construction project with the promise of good wages, housing and contracts. This failed to attract the necessary number of workers and thus the Japanese resorted to violence, by rounding up innocent civilians and imprisoning them. This included around 90,000 Burmese and 100,000 Malayan Tamils.

The death rate suffered by the workers was incredibly high and made worse during the final months of the war, when Allied bombing compounded the already horrendous circumstances.

Meanwhile the POWs were transported from various locations. The British came from the Changi Prison in Singapore and arrived at Camp Nong Pladuk to build the work camps along the railway. Other prisoners, including 3,000 Australians, left the same prison and took a sea route to begin work on airfields and infrastructure before the railway project began.

By October 1943, the civilians who had been forced into labour were moved to ‘rest camps’ where they remained for the duration of the war and for some time after, with individuals still in camps as late as 1947. For these innocent people, the end of the war did not bring the same relief as it did for POWs who were subsequently evacuated. Instead, survivors were forced to remain, very often succumbing to the fatal cocktail of diseases which were spreading rampantly in the camps.

Conditions for the duration of the building project and for those stuck in camps after the war were atrocious with no hygiene, hardly any medical supplies and poor nutrition levels.

Asian labourers bore the brunt of this, with almost half of them perishing by the end of the war, whilst Allied POWs lost more than a quarter of their men. Regular beatings of those deemed not working hard enough was a common occurrence, and many of the men were working whilst suffering from severe diseases.

Nutrition was non-existent, consisting of gruel made up of rice and sometimes vegetables, resulting in widespread malnutrition and susceptibility to diseases such as beri-beri, cholera, malaria, dysentery and flesh-eating ulcers.

Those that did survive returned home in a visually alarming state, with bones protruding from the body, many of the labourers looking more like survivors of European concentration camps than returning soldiers.

The suffering was in some cases recorded by the prisoners in the camp, including military accounts such as John Coast’s Railroad of Death which was published in 1946, describing the living and working conditions as well as the real human toll and nuanced experiences of individuals in the camp. Moreover, others made artistic contributions using brushes made of human hair and paint substitutes of plant juice and blood. Their work served as a permanent reminder and evidence of the suffering which in some cases was even used during the subsequent trials.

After the war, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal was convened, resulting in twenty-eight high-ranking Japanese military and political leaders being tried, including prime ministers, cabinet members, and military commanders.

Following the trials conclusion, other domestic tribunals were convened by Allied nations including post-war Australia which saw 924 Japanese servicemen tried with 644 convictions and 137 executions.

Whilst the brutality of the Japanese regime was recognised as a war crime, the issue of compensation and reparations was not so readily addressed.

Japan agreed to sign a treaty which offered reparations for the Indonesian and Burmese governments. Meanwhile, the Allied forces provided a proportion of compensation to POWs, however in 1951 such agreements were seen as severely lacking, with one soldier receiving just £76. Given the magnitude of the suffering and torture endured by POWs, more recognition in the form of reparations was demanded.

In the years that followed, in a process involving numerous governments, reparations for 60,000 Allied POWs was agreed upon, however no provision was arranged for anyone who was a colonial subject at the time.

For those that survived the construction of the Burmese Railway, their life would never be the same. The lack of political recognition of their suffering continues to be a blight for all sides involved. The Death Railway took thousands of lives and ruined countless others; the memory and sacrifices of those who constructed it should never be forgotten.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th February 2025