“Poor blind man! He has better clothes and more money than you or me; it’s all done to excite pity!”

This remark was made of a blind Silhouette cutter who worked outside on Hungerford Bridge in Victorian London. At the time, ignorance of eye conditions and their causes was rife. The actual main causes of sight loss were diseases such as smallpox, measles and whooping cough, natural eye defects, injury or inflammation to the eye, cataracts and glaucoma.

However, many afflictions were still put down to ‘God’s judgement’, thus making God-fearing Victorians afraid to associate with such people should the same thing happen to them. Most Victorians found sight loss discomforting and had little empathy for the blind. Blind people, or any disabled person for that matter, were seen as objects of pity but were also feared or treated as fakes, like the man above.

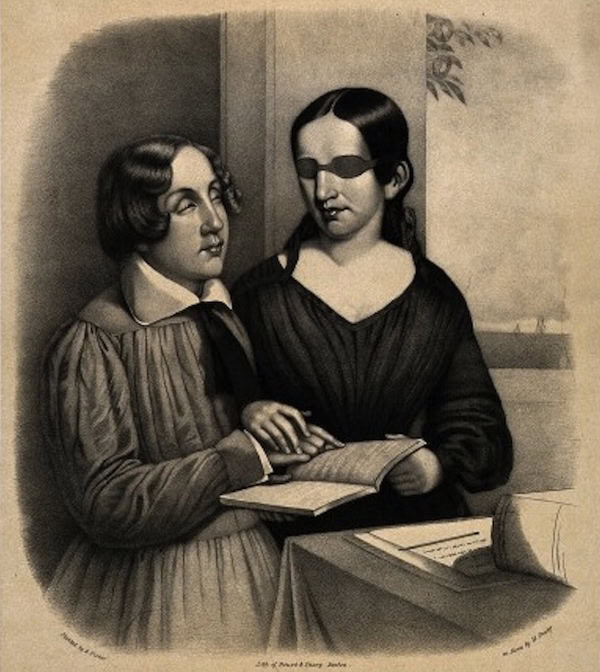

The blind themselves, though, just got on with life, usually with the help of walking sticks or a guide. A family member or a local young boy or girl would act as companion to the blind person, helping to guide them on the streets and in their work. They never strayed too far from their home and followed the same route every day, using the sounds and smells of the streets to guide them.

Families helped with work, food and shelter. There wasn’t any government help and so each blind person came up with their own unique way of coping in an already difficult world.

The journalist Henry Mayhew interviewed many blind people for his series of newspaper articles ‘London Labour and London Poor’, first published in book form in 1851. He revealed how blind people faced poverty and indifference. A blind street reader of Scriptures (the only literature available in Braille) told Henry, “Once I counted in Mornington Crescent, as closely as I could, just out of curiosity and to wile away the time, above 2000 persons, who passed and re-passed without giving me half-penny.”

Unfortunately, this sad story is not uncommon but there were plenty of kind philanthropists who witnessed these everyday disasters and poured their time, energy and money into solving them.

Institutions for the Blind

The late Georgian era saw Edward Rushton set up the Liverpool School for the Indigent Blind in 1791. London’s School for the Indigent Blind swiftly followed in 1799. The London school accepted pupils aged 10 to 18 where they received religious and moral instruction and learned skills in basket-weaving, mat-making, spinning and weaving. The plan was for the residents to eventually earn a living working from their own homes. By 1838, it held 200 residents, but admittance was only allowed after an assessment of needs, with those deemed the most deserving gaining a place. In 1866, Worcester College for the Blind Sons of Gentlemen opened its doors to provide a variety of education. Edward Elgar, arguably England’s greatest composer, was professor of the violin, indicating the opportunities on offer to these middle-class blind students.

Hindrance or help?

It soon became apparent that these schools fulfilled a societal need and, because demand soon outstripped supply, charity-run residential schools also opened up across the country. These schools were met with fierce criticism as many campaigners felt that blind children were put out of sight and out of mind, which did not help the Victorian attitude to blind people.

They also argued that, by treating the children and young adults like prisoners, they were condemning them to a life of poverty due to their lack of education and skills and a certain amount of learned helplessness. Many institutions insisted on a narrow curriculum of basket-weaving, brush-making and mattress stuffing. Campaigners realised this was not conducive to a healthy body or mind, with many bright and enquiring young minds denied access to reading, writing, maths and science.

In contrast, on the continent, many imminent doctors insisted that blind children should be educated amongst their peers. Johann Wilhelm Klein believed this as early as 1804 when he founded his school for the blind in Vienna. John Bird, a British surgeon who became blind as an adult, advocated education in the community. He believed that blind children or adults should be given money to supplement the family’s income rather than be segregated from their families in an institution miles away, much like a prisoner. If blind people were isolated, he argued, how could society learn to respect and help them?

Despite the concerns of campaigners, there is very little doubt that the institutions saved many a blind person from debt, disease and an early death. By 1899, there were 43 day schools for disabled children in London alone, catering for the educational needs of 2000 blind, deaf and disabled children. In fact, many of these Victorian special schools stayed open well into the twentieth century, albeit providing far superior curriculums and opportunities for their pupils.

A modern outlook.

Nowadays, thanks to several Disability Acts, 70% of vision impaired pupils are able to attend their chosen mainstream secondary school, with the special schools focussed on catering for multi-sensory needs.

Modern schools are a far cry from the Victorian institutions of 150 years ago, but there are still echoes in the units set up in schools to help with blindness and other disabilities. Campaigners argue that mainstream schools need to recognise that partially sighted and blind pupils require equal treatment not special treatment. It seems that John Bird’s Victorian vison is yet to be clearly established.

Shona Parker is a writer and blogger of English social history. Her first book ‘How the Victorians Lived’ is available now from Pen and Sword Books Ltd, Amazon and Waterstones. You can read more of her writing at www.backinthedayof.co.uk and follow her on social media: linktr.ee/shonaparkerhistory.

Published: 15th July 2024.