The Second World War was a global conflict, one with many battlegrounds, numerous fronts and several participants.

Frequently overlooked, the conflict zone of South East Asia was a long and arduous battleground involving an international coalition of troops fighting against the might of the Imperial Japanese Army.

The campaigns which were fought took place across the region in India, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, Indochina, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.

Beginning in 1940 when the Empire of Japan invaded French Indochina, the conflict soon escalated and took on a new international dimension with the bombing of Pearl Harbour. This was followed by simultaneous attacks in the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand and Malaya, which reflected Japan’s intent and its capabilities.

The response from the United Kingdom, United States, Canada and the Netherlands was a declaration of war on Japan on 8th December 1941. The following day both China and Australia followed suit.

Sometimes referred to as the Pacific War, it was geographically the largest theatre of war involving the Pacific Ocean, South West Pacific theatre, the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Soviet-Japanese War. With conflict already existing between the Republic of China and Japan dating back to 1937, the international complexity of the fighting was widened when the UK and USA entered the war against Japan in 1941.

During this time, the region played host to some of the largest naval battles in history whilst aerial bombardment also served as a key aspect of the fighting.

Japan referred to this conflict as the Greater East Asia War, in acknowledgement of both its war against China and the Western Allies.

The key participants in the Allied force included the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, China and representatives from India and the Philippines, forming what became known as the Pacific War Council.

Meanwhile, Japan conscripted many of its soldiers from colonies based in Korea and Taiwan, bolstered by collaborators from Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, British Malaya, British Borneo and French Indochina.

Whilst the whole region experienced conflict, between 1942 and the end of the war, there were four main conflict zones: China, the Central Pacific, South East Asia and South West Pacific.

The Japanese some years earlier had set their sights on various locations in order to expand the Japanese Empire. One such location included the Dutch East Indies which was an attractive prospect due to its energy reserves.

Observing an increase in Japanese hostility, embargos were imposed on Japan by Western powers who stopped selling oil, iron ore and steel to Japan.

In April 1941, formal plans for war against the West began at the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters. Originally designed to be limited in scope, by November the plans were finalised and designed to force a negotiated peace by the US which would recognise Japan’s superiority and control in Asia.

Instead, full-blown conflict soon followed involving an international force. Initially military manoeuvres did not go according to plan for the Allies, as two major British warships were sunk by the Japanese in an air attack off the coast of Malaya in December 1941.

Subsequently, the government of Thailand chose to ally itself with Japan a few days later and Japan successfully invaded Hong Kong and forced its surrender by Christmas 1941.

The next month invasions of Burma, the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines ended in Japanese victory, as did the Battle of Kuala Lumpur. This was aided by Japan’s superior resources in both air power and tanks which drove back Allied forces.

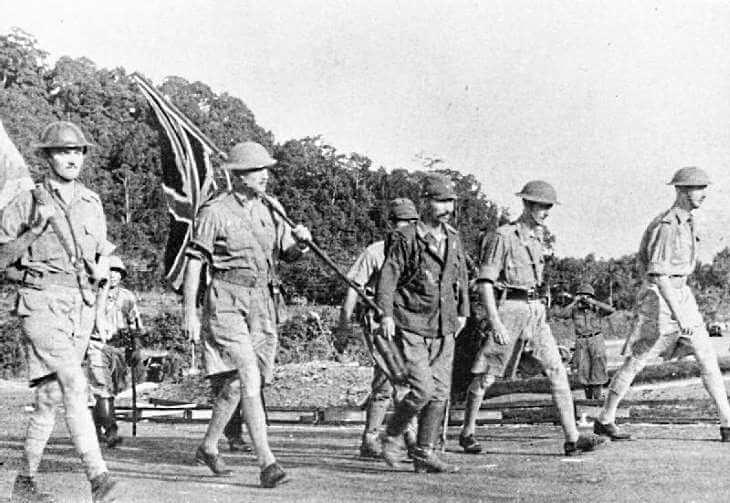

Meanwhile, one of the largest surrenders in British military history took place during the fall of Singapore, forcing an Allied surrender to the Japanese in February 1942. Prime Minister Winston Churchill would later refer to this as ‘the worst disaster…in British history’.

The shocking military defeat was compounded by the large number of Allied troops taken as prisoners of war. Thought to be around 130,000 men, their experiences in detention were horrific and resulted in many fatalities with men succumbing to disease and malnutrition in large numbers.

Conditions for prisoners of war in the region were appalling with men routinely subjected to forced labour, a chilling regime of violence and wanton neglect.

From 1942, POW’s were used to build the Burma-Thailand railway which became known by its more sinister name, the ‘Death Railway’. The railway was constructed by a combination of captured Allied soldiers and Southeast Asian civilians who were abducted and forced to work by the Japanese.

The railway soon became known for its high mortality rate as a result of atrocious conditions, malnutrition and rampant diseases such as malaria and dysentery.

It was not only the POW’s who succumbed to these tropical diseases however, as many of the British troops still fighting also became victims.

By 1943, the statistics reflected an alarming situation of fatalities by disease rather than battle wounds, with 120 soldiers evacuated for sickness for every one soldier evacuated with wounds.

Such issues were compounded by the climate which troops had to endure with high levels of humidity, constantly high temperatures as well as thunderstorms and monsoon conditions. For many British soldiers, Burma’s treacherous topography combined with unfavourable weather conditions made fighting and travelling a lot more difficult.

After Japan’s invasion of Burma, many communities were forced to flee to safety in India, including Burma’s Indian, Anglo-Indian and British communities. Many who made the journey never reached their final destination, struck down by a combination of disease, exhaustion or malnutrition in the desperate bid to flee.

In June 1942, the Japanese had successfully forced the British, Indian and Chinese troops out of Burma.

The following year, British and Nepalese Gurkha troops who were known as ‘Chindits’ began a long distance raid behind enemy lines commanded by Brigadier Orde Wingate.

By 1943, the 14th Army was formed in India and served under the command of Lieutenant-General Bill Slim whose daring tactics won him great admiration from his troops.

One of the most prominent fighting forces and largest military units which fought in the region, its main mission was to retake Burma from the Japanese which required a great deal of effort and military acumen which was often hindered by a lack of resources.

Under Slim’s leadership, thousands of troops from several Commonwealth countries served in the Fourteenth Army including Indian, Gurkha and African soldiers. This included the 81st West African Division which included men from Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Gambia who fought in the Arakan region of southern Burma during the last two years of the war.

By the spring of 1944, Japan had set its sights on India with the goal of capturing an important garrison town of Imphal, thus hampering British efforts to return to Burma. This culminated in two battles at Imphal and Kohimar which resulted in a significant Allied victory and marked a turning point for the troops.

Whilst fighting took place on the ground in Burma, the Asian theatre of war also played host to some of the most significant naval battles including the Royal Navy’s Pacific Fleet operations.

By 1944, after the success of the Battle of Normandy and the subsequent liberation of Nazi-occupied territory in Europe, naval resources thus became available to be sent to Asia.

In January 1945, Operation Meridian was launched (also known as the Palembang Raids) which resulted in a series of air strikes against Japanese oil targets in Sumatra. The mission was successful in severely hampering Japanese fuels supplies.

Meanwhile, aircraft carriers were heading towards Sydney to join the British Pacific Fleet.

By the latter stages of war, when the main forces had left the Indian Ocean, older vessels were left behind to form the majority of the naval force but would continue to manage to launch significant operations including landings on Ramree and Akyab in an effort to recapture Burma.

Whilst significant efforts and advances were being made on both land and sea, the final contributing factor for Allied victory was the use of aircraft.

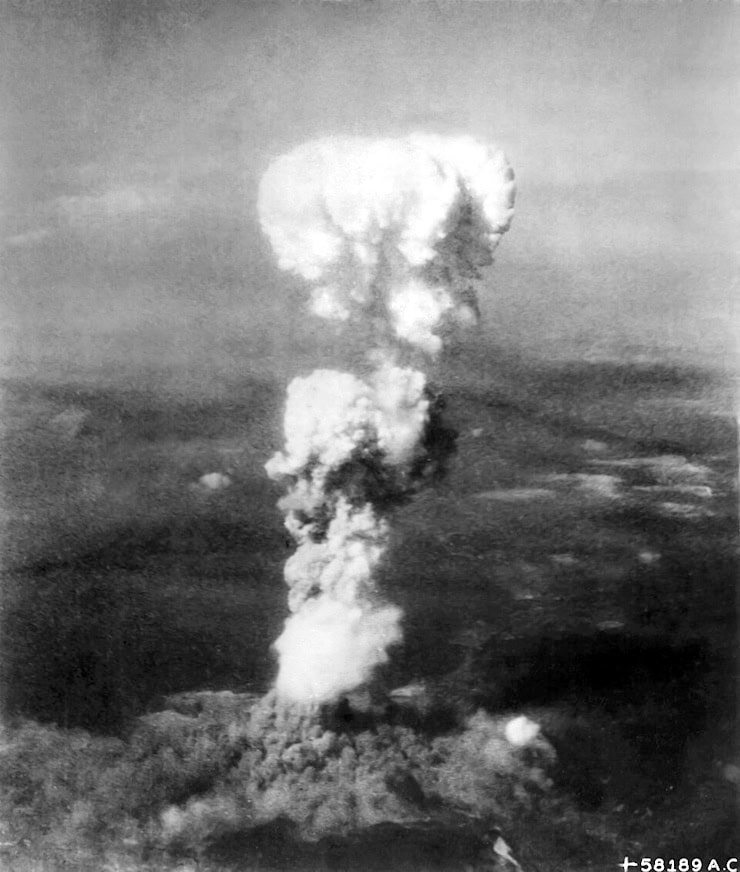

By the summer of 1945, American raids had destroyed significant areas of Japan, including major locations.

On 6th August, the city of Hiroshima was hit by the atomic bomb causing a blast and wave of radiation which would have repercussions for generations.

Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki, leading to thousands of fatalities.

A few weeks prior, the Allied forces had called for the unconditional surrender of the Japanese forces in the Potsdam Declaration, promising ‘prompt and utter destruction’ in an ultimatum which was subsequently acted upon.

After receiving consent from the United Kingdom as part of the Quebec Agreement, orders for the bombing were subsequently issued.

Once the bombs had been dropped and the devastation became evident, Japan announced its surrender to the Allies on 15th August, codified by the official signing of surrender on 2nd September 1945.

The finality of war had brought relief for millions, however remembrance of the conflict remained dominated by events in Europe.

The war in Asia involved immeasurable sacrifices, the endurance of unspeakable atrocities and the participation of a multi-national fighting force, events and experiences which should never be forgotten.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 11th August 2025