In this Sussex seaside town, where the sea is nearly two miles away, explore the labyrinth of cobbled streets all steeped in history, secrets stowed away and ghosts uncovered. Rye’s physical location means the town has seen all the action: invasions, smuggling, flooding, a few more invasions, and shipwrecks!

Let’s start with the invasions. Situated on the south coast of England and where the English Channel is at its narrowest, Rye was often the first port of call for an intruder sailing across from North West Europe. (This was when it was a fully functioning harbour, before it was separated from the sea by marsh.)

The French regularly attacked or raided Rye and even the Spanish did on occasion. Some attacks were worse than others; in 1377, a French assault resulted in the complete desolation of the town by fire. The bells from St Mary’s Church were also stolen on this occasion but the men of Rye and neighbouring settlement Winchelsea sought revenge and set sail for France. This retaliation was fruitful as they returned with the bells and an assortment of other goods that had been stolen on a previous French attack!

In recognition of Rye’s role in defence on the south coast, the town was made a Cinque Port in 1336. This meant it became one of a group of ports on the south coast which received privileges, including exemption from tax, in return for maintaining ships for defence, a scheme originally introduced by Edward the Confessor in the 11th Century.

Prior to the rule of Edward the Confessor, the region along the south coast – including Rye – was under the rule of the Abbey of Fecamp in France. This was returned to the English crown in 1247 by Henry III, except for a small region to the north of Rye. This is still known as Rye Foreign despite it belonging to England once more since the Reformation.

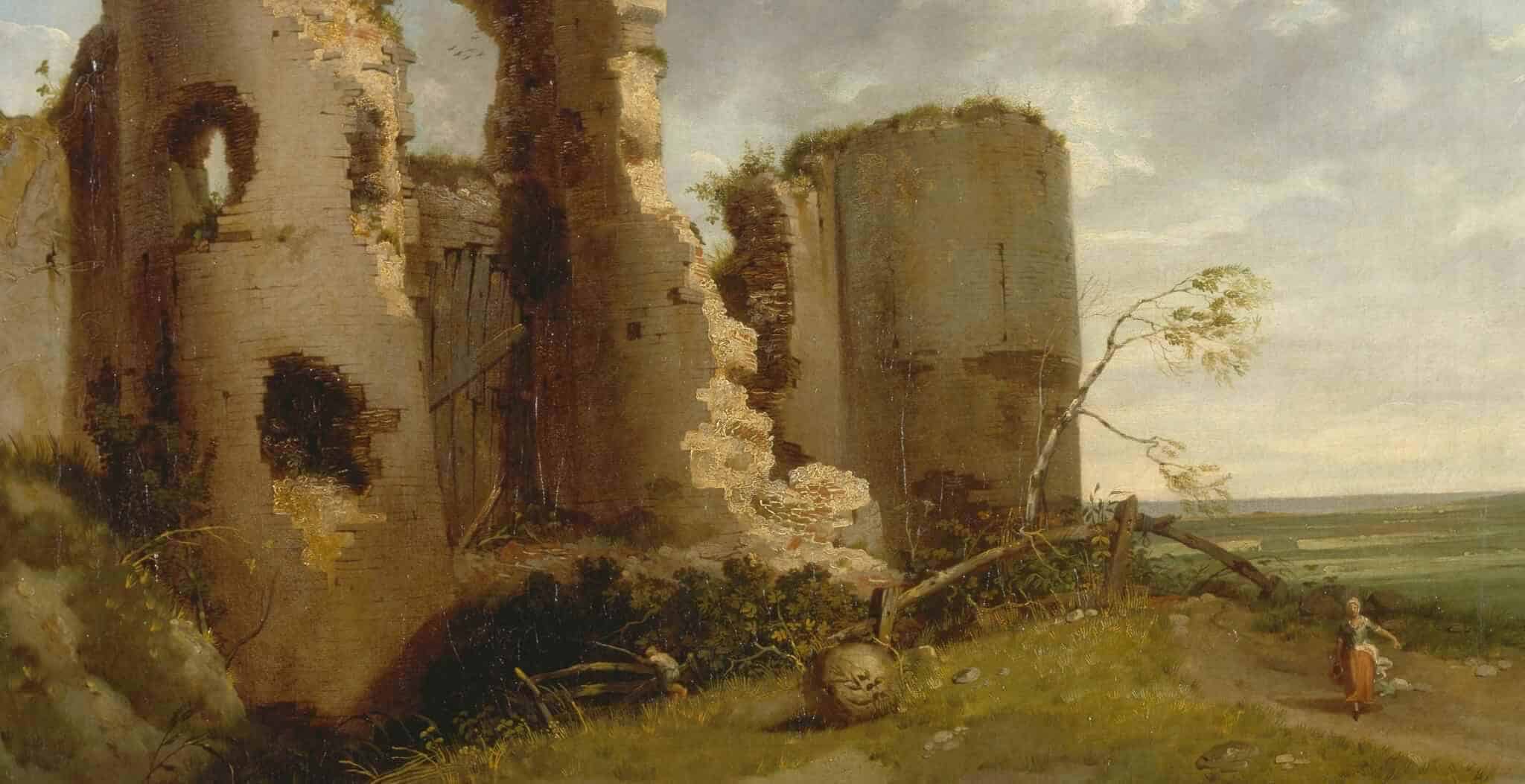

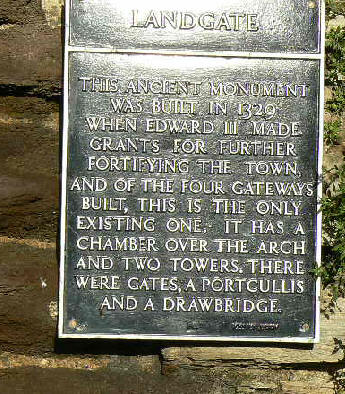

Under English rule, Rye underwent regeneration and fortification. This began with the building of the town wall and four gates; Landgate, Strandgate, Baddings Gate and Postern Gate. The strength of this defence was tested when the French invaded again in 1449, once more setting fire to buildings, although not causing the scale of devastation seen previously. Modernisation of defence was implemented in the 15th and 16th centuries but today only one of the gates remains; the Landgate.

The other famous defensive structure that still remains in Rye is the Ypres tower. The view of the bustling harbour (now farmland) and then out to sea would have been a distinct advantage, but nowadays it is purely for pleasure. This building was thought to have been intended as part of a defensive castle that never materialised. Unlike the walls, the tower survived time and further attacks from the French.

By the 16th Century the sea had receded. Rapid siltation created the Romney marshes that today separate Rye from the incoming tides. Longshore drift moved shingle along the coast and deposited the load in a strip out from the headland. The strip ran parallel to the coast and began to block off the Romney Bay, leaving an area of calm water and encouraging more deposition.

The marsh was still unstable in the 12th century, flooding and breaching the embankments that were in place at high tides. A tax, called a “scot”, was enforced in the 13th century to pay for maintenance of waterways and flood protection. The phrase “getting off scot free” comes from this as the people who lived on higher land and out of threat from flooding were exempt from paying this tax. It was a series of large storms in the 13th century that finally pushed a vast amount of shingle up the coastline and ensured that the marsh could successfully silt up until it became useful for grazing of livestock.

Livestock like sheep provided a trade for the area: wool. The seas not only brought those with the intention to conquer English land, but also those who sought, bought and dealt goods into and out of the country.

Smuggling was rife along the south coast and Rye, with its narrow streets and dark headlands, was an ideal place for the storage of illegal cargoes like wool. The smuggling industry began when Edward I introduced the Customs system in the 13th Century. The response was to smuggle goods like wool, cloth, hides and also gold and silver out of the country. Further restrictions made towards the 17th Century made smuggling much more of a lucrative business as even commonly used products like candles or beer had new tariffs forced on them.

The exportation of English wool became heavily restricted in 1614 (and then again later that century) in the hope of protecting the British cloth industry. This created an upsurge in the illegal exportation of wool, or the “owling” trade. Rye, where wool was produced, was so close to France and the European markets that even the death sentence didn’t prove to be a good enough deterrent against smuggling behaviour! It became a hanging offence to wear a balaclava like garment called a “bee-skep” (or any other mask-type adornment for that matter) while in the act of smuggling. By the 17th Century, smugglers worked in large, organised, heavily armed groups and had expanded into the import of luxury goods like tea as well as the export of English contraband.

Many industries have been adopted by Rye. Pottery, produced from the 11th century onwards, is one such industry. Originally, connections with France brought skilled craftsmen to the area and a unique pottery named “hopware” was developed in the town (where hops and hop leaves were sealed against the clay). Rye pottery was then modernised by a pair of brothers – John (Jack) & Walter (Wally) Cole – who specialised in contemporary 1950’s designs. Tourism is also a major industry for this small but picturesque town; it boasts spectacular scenery and wildlife, history and scandal and opportunity for a quiet coastal break.

Getting here

Rye is easily accessible by both road and rail, please try our UK Travel Guide for further information.

Museums

View our interactive map of Museums in Britain for details of local galleries and museums.