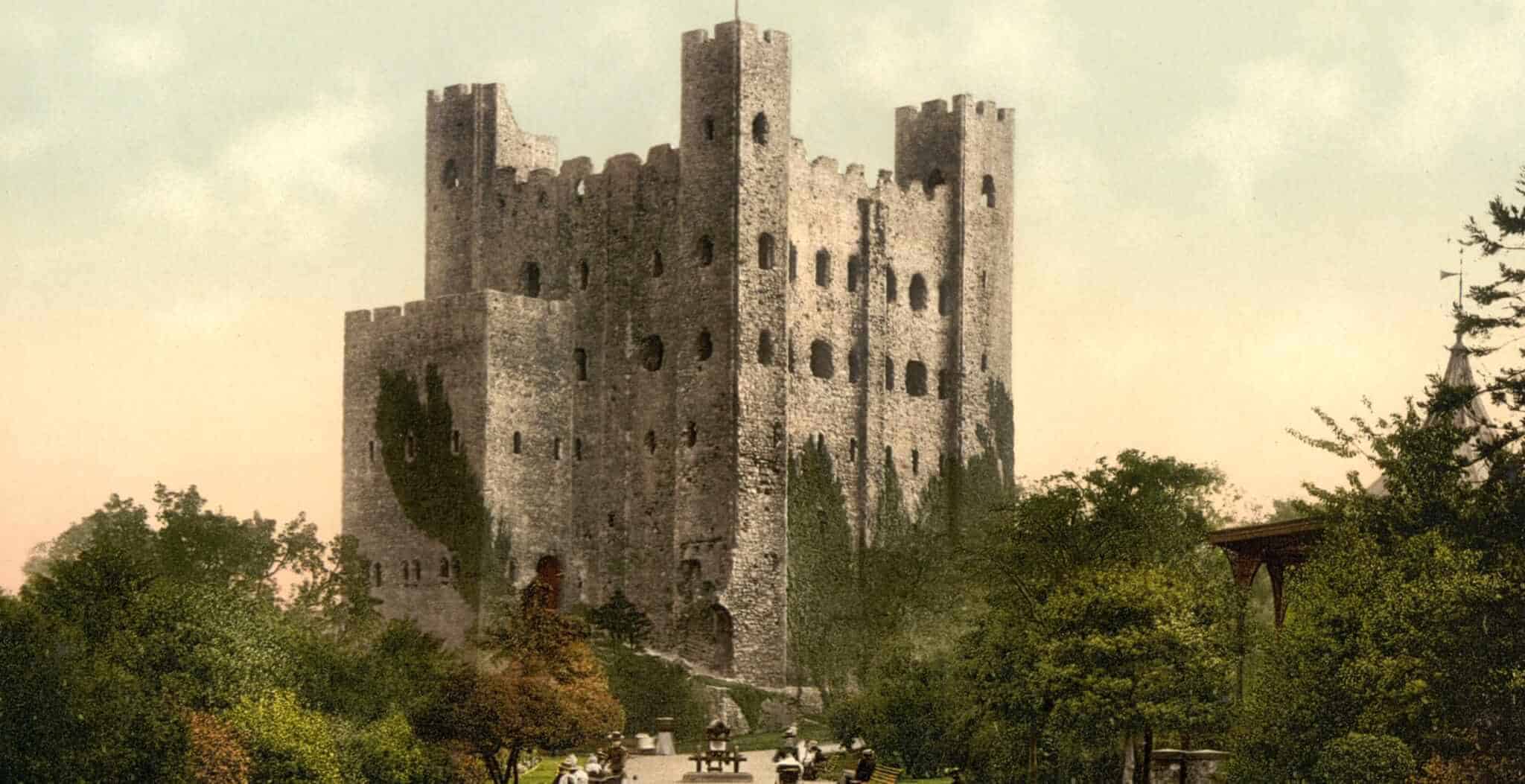

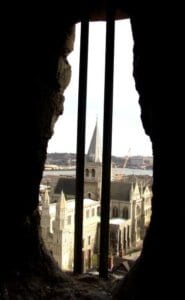

Perched high on the site of an old Roman settlement Rochester Castle dominates the skyline. Strategically positioned on the east bank of the River Medway, the massive architectural impact of the old ruined Norman fortifications is evident whichever angle you approach it from. The equally impressive Rochester Cathedral stands at the base of the castle, another architectural jewel in this small but historically rich south eastern town.

In 1087 Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester began the construction of the castle. One of William the Conqueror’s greatest architects, he was also responsible for the Tower of London. Much of what you see remaining of the walled perimeter remains intact from that time. William de Corbeil, Archbishop of Canterbury was also a contributor to this grand castle building project. Henry I granted him custody of the castle in 1127, a responsibility that lasted until King John seized the castle in 1215.

On the 11th October 1215, William de Albini and Reginald de Cornhill, accompanied by a large group of knights, defied King John. The siege lasted seven weeks whilst the King and his army battered the castle walls with a five stone-throwing machine. The King’s army using a bombardment of crossbows were able to breach the southern wall and drive back de Albini and Cornhill’s men to the keep.

The King’s sappers meanwhile were busy digging a tunnel which led to the southeast tower. The plan to destroy the tower was executed by burning the fat of forty pigs which burnt through the pit props and destroyed a quarter of the keep. The defenders of the castle continued the warfare undeterred, and fought bravely amongst the ruins. Despite their valiant efforts starvation ultimately took its toll and they were forced to surrender to King John and his army. The castle was subsequently taken into the custody of the Crown.

A twenty year period of renovations followed, under the supervision of King Henry III, John’s son. The walls were rebuilt and the new tower constructed in order to protect the more vulnerable southeast corner from a similar invasion.

The Barons’ War of 1264 saw the castle become the setting of yet another battle, this time between Henry III and Simon de Montfort. The castle came under fire from rebel armies. Roger de Leybourne, the leader of the castle’s defence, was forced back into the keep after less than twenty-four hours of fighting. Stone throwing caused extensive damage and a mine tunnel was under construction when de Montfort abandoned the siege. News had came of an approaching army under the command of the King. Once again repairs were needed but these would not occur for another 100 years until Edward III rebuilt whole sections of the wall and later, Richard II provided the northern bastion.

The bailey, now an attractive expanse of grass and trees where many families choose to picnic, would not have looked so appealing in the time of the Normans. Most likely covered in dust and a sea of mud in the winter months, many people would have been working in the bailey from blacksmiths to carpenters, cooks and traders. The conditions would have been cramped, not to mention the animals, horses and dogs living within the confines of the castle.

The Constable’s Hall was the location of everyday activities in the castle, particularly business matters, including the local courts. One might imagine luxury when envisaging castle life, but life in Norman castles was often very rudimentary, even for the nobility. Furniture was minimal and food was basic, a diet of beef and pork as well as a huge number of chickens were consumed. Food was eaten with fingers, no cutlery or plates were used. Hygiene in these living conditions became a huge issue as washing facilities were non-existent. Eventually, the old ways of the Normans were replaced with new ideas and by the end of the twelfth century comfort and hygiene played a bigger role.

Explore, admire and discover the rich history this town has to offer!

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Tours of Historic Rochester

For more information concerning tours of historic Rochester, please follow this link.