As you travel through the South Hams, you may well pass through the picturesque village of Modbury. A few miles inland from the coast, to holidaymakers it’s probably best known as a way marker on the drive to the beach at Bigbury. With some colourful and quality shops, pubs and cafes, there’s already enough reason to stop and enjoy Modbury’s mellow vibes. But linger a little and you can uncover a fascinating and sometimes dramatic history, from the medieval church to Civil War battlefields.

The name Modbury almost certainly comes from the old English words ‘Moot’ (meeting place) and ‘Burgh’ (defended enclosure). The location of the original ‘Mootburgh’ has been lost to time, but was most likely on one of the hilltops which surrounds the small valley in which the modern village-centre sits. It is unsurprising that the village started life as a meeting place; the ridges around Modbury show evidence of prehistoric trackways, likely connecting local settlements such as Blackdown Rings with dispersed farmsteads. Modbury also lies near the line of a Medieval east–west route between Plymouth and Dartmouth that followed the higher, drier ground rather than the valley bottoms. This ridge road would have been used for trade, livestock drives, and military movements. It is also very near to the Erme and Avon estuaries, perhaps acting as an important inland meeting place for travellers and traders transiting between the coast and the hinterland.

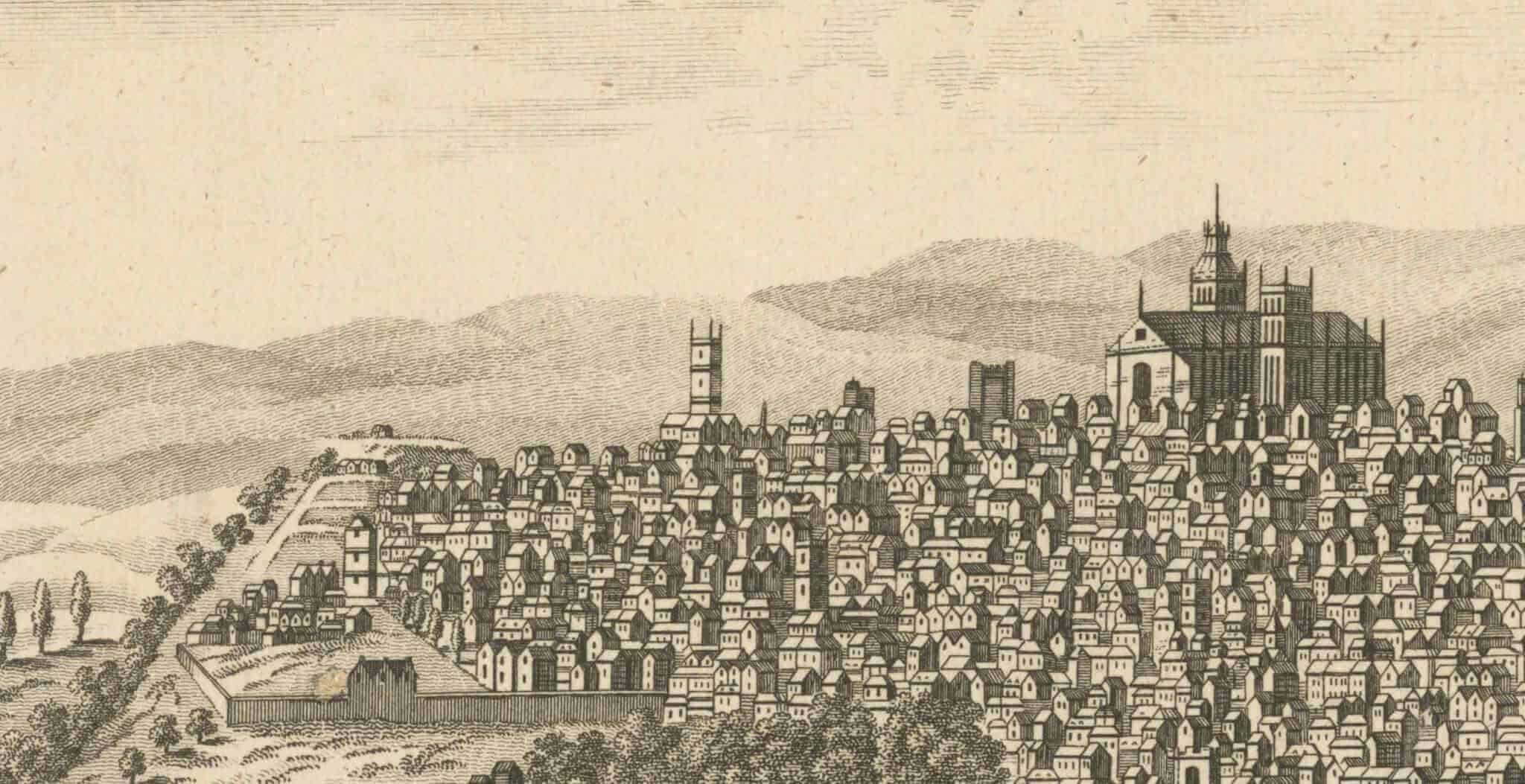

This may have contributed to Modbury’s early growth – when first recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, it is a modestly sized settlement, but by 1199 it had grown sufficiently to hold a weekly market fair. This indicates a growing population and local prominence. A ‘John de Modbyri’ was recorded at Dartmouth in the 1300s – perhaps he had moved there as part of the trading network between the two places and become known by association with his native village. Growth was also boosted by the establishment of a priory at Modbury by the de Vautort family, who had gained significant lands in Devon following the Norman Conquest. Their Manor House and the Priory stood near to each other, and though the Priory was long gone even before the Reformation, you can still visit the beautiful church that may once have been a part of it.

St George’s sits a short walk up the hill from the village centre, set behind the main road amidst a serene cemetery. The main body of the church dates to the fourteenth century, with dendrochronological analysis showing that the church received a new roof in the 1600s. Its impressive spire dates to the 17th century (built after the original was destroyed by lightning in 1621). The stature of the church attests to the prosperity which Modbury enjoyed throughout the Middle Ages, as its wool and cattle markets made it an important local centre.

However, the very qualities which had encouraged Modbury’s growth meant that, during the English Civil War, it became a site of operational importance. As with most of the rural South Hams, Modbury was staunchly Royalist, with prominent local landowners (such as the Champernownes, the contemporary lords of the Manor) declaring for the King. This contrasted with staunchly Parliamentarian Plymouth, a port with a strong puritan presence, which was surrounded by royalist country in South Devon and Cornwall. There, the Scottish Parliamentarian Colonel Sir William Ruthven plotted to strike at the Royalist heartland – and Modbury was an ideal target. In the cold early hours of 7th December 1642, Ruthven mustered a small force of 200 – 300 horsemen, including many experienced Scottish mercenaries, and set out from Plymouth under cover of darkness to silently advance on Modbury. There, a freshly raised Royalist force had gathered, and Sir Ralph Hopton, the King’s senior commander in the West Country, was holding a council at Champernowne’s Manor House.

Ruthven’s intent was to rout the royalists and kill or capture Hopton. The Parliamentarians successfully closed in to Modbury without raising an alarm. As dawn broke, Ruthven’s men, cold and wet but fired with adrenaline, charged out of the surrounding woodland and burst into the Royalist camp. Taken by surprise, the King’s novice soldiers turned and fled for the hills. Ruthven’s force rampaged through the village, capturing several Royalist leaders, including a member of the Champernowne family, and burning down the Manor House. However, Sir Ralph Hopton fled, denying Ruthven’s raid its central objective – though he likely went back to Plymouth well satisfied with his day’s work.

Battle would return to Modbury in short order. By February 1643 a Parliamentarian force of around 8,000 men from North Devon had based itself at Kingsbridge under The Earl of Stanford, with the intent of relieving the pressure on Plymouth. In response, Sir Ralph Hopton gathered a fresh Royalist force of 2,000 at Modbury – mindful of his embarrassment in December, he set about barricading the southern and eastern approach to the village and posting musketeers in the hedgerows. The Parliamentarians left Kingsbridge on 22nd February, marching broadly along the route of the modern A379 road. William Lane, Vicar of Aveton Gifford, was attempting to build a fort to impede their advance but did not complete it in time (he would later be similarly unsuccessful in trying to disrupt the capture of Salcombe Castle).

The Parliamentarians reached the outskirts of Modbury in the early afternoon and began trading shots with Hopton’s defenders. There followed a protracted firefight as the Royalists, outnumbered 4-to-1, fell back field by field. Their resistance was stiff, and only seems to have waned as they ran short of ammunition – reportedly they started stripping roofs of lead and melting it down for bullets. Ultimately, in the early hours of the morning, they retired to the ruins of the Manor House and the churchyard, where it became obvious that the cause was hopeless. The Royalists turned in headlong retreat along the secluded path behind the church, using the cover of night to disperse into the countryside. It must have been a desperate scene as hundreds of men sprinted along the muddy track in the freezing darkness of a February night – to this day, the path is known as ‘Runaway Lane’.

The Manor house was never rebuilt, and its remnants were sold off for building materials in 1705. Modbury recovered from the war to retain local significance, but from the 19th century it steadily declined. Mechanisation and the centralisation of the economy in large towns drove the population down, as did the lack of a railway connection. The last cattle market was held in 1944. Nonetheless, Modbury has rebounded today to become a significant pit-stop for travellers, reviving some of its historic role as a meeting place. The modern cafes, pubs and gift shops (including the UK’s only surviving traditional Toy Soldier Shop) take the place of the old market. If you make your own way to Modbury, you can enjoy this serene setting while imagining the dramatic history that once took place in these quiet streets many centuries ago. You can even stroll down Runaway Lane – in the absence of pursuing Roundheads, you’re best off doing so in daylight hours.

Mike Edwardson is a professional analyst and writer with an MA in History from The University of Sheffield. Passionate about uncovering the lesser-known stories of British history, Mike combines his analytical skills with a love for storytelling to bring the past to life.

Published: 23rd September 2025