Genius can emerge in the most unlikely places.

From the Brontë sisters, to Charles Dickens, to William Shakespeare himself, history is replete with examples of people whose lives show how true this is.

In Keats House, located in Hampstead, North London, you find a place where another talented individual – John Keats, arguably one of the greatest poets in the English language – bloomed against the odds.

Keats House, photo by Toby Farmiloe

Keats House, photo by Toby Farmiloe

Viewed as mere bricks and mortar, Keats House is not a particularly distinctive example of early nineteenth century architecture. With its wide, white-washed frontage, tall Georgian windows and its pleasant garden, it was built between about 1814 and 1816 as a pair of separate semi-detached homes and known originally as “Wentworth Place”.

Emerging out of the subterranean agony of the London Underground, passing along quaint yet bustling Hampstead High Street and then turning down the more peaceful, gently sloping Keats Grove away from the sound of traffic, lined with leafy trees and expensive Victorian homes, it’s like moving further back in time with each yard you pace. When you arrive at the house, you find some of the original atmosphere of tranquillity that, it’s pleasing to speculate, helped Keats’ eminent poetic brain to soar.

Keats first visited here in 1817. In those days, London hadn’t yet expanded its current size and Hampstead was still a sequestered country village.

Though contemporary accounts suggest he did well at it, Keats had grown tired of his existence as an apprentice apothecary and surgeon at Guy’s Hospital at London Bridge. After a life touched with tragedy, following the deaths of his father when he was a child and then the demise of his mother and brother from tuberculosis, Keats left the strains and pressures of London and medical training and came to Wentworth Place to establish himself as a full-time poet and find inspiration in his bucolic surroundings.

At that time, the liberal writer and critic Charles Wentworth Dilke and his friend Charles Brown lived in the house with their families. In December 1818, Brown invited Keats to “keep house” of one half of Wentworth Place with him in return for £5 per month and half the liquor bill.

Interior of Keats House today, photo by Toby Farmiloe

Interior of Keats House today, photo by Toby Farmiloe

Today the whole of the building is given over to a museum on Keats’ life, works and his time in the house. Though Keats only resided here for not even two years, occupying only a few of the rooms, you find the imprint of his presence everywhere, as though he’s just stepped out of the room, or outside into an eternity of straining his sensibilities to capture the beauty of moss’d cottage-trees bending with apples in neighbouring gardens or the forlorn and haunting song of the nightingale deep in Hampstead Heath.

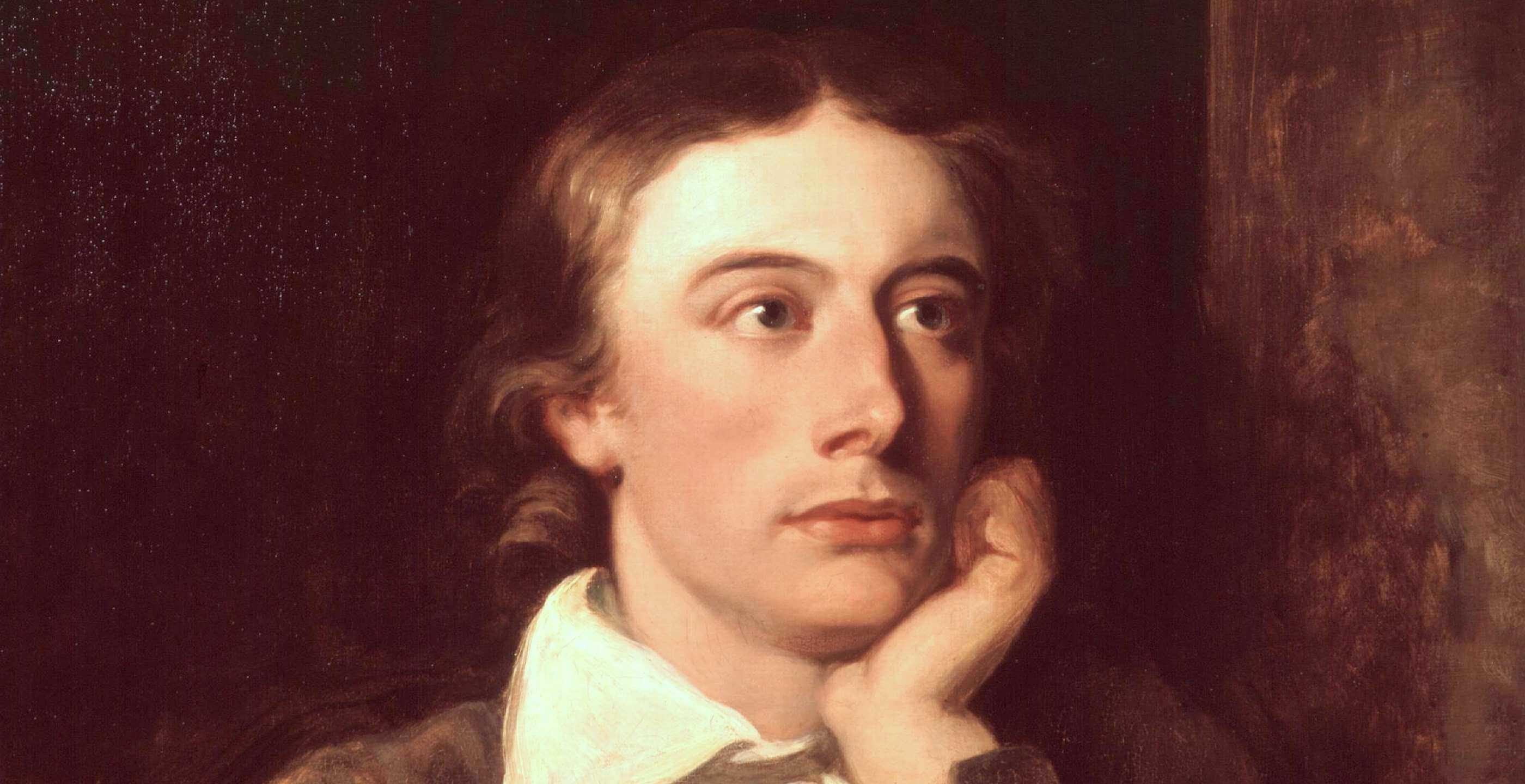

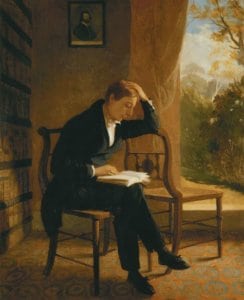

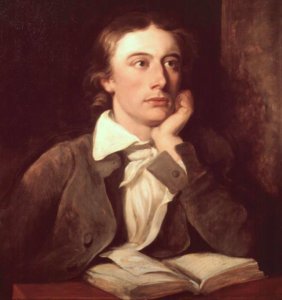

You can imagine him quite easily – aided by the bust of his likeness on display – probably troubled at times by his shortage of money, driven by his desires to find beauty in everything (which, he said, “overcomes every other consideration”) and to fail “sooner than not be among the greatest”. In one room you can picture the young man scratching away in the silence at a table near a window, looking out on to the garden as if for life. In another, you can almost see him again, where two chairs and a portrait of Shakespeare on the wall have been arranged in exactly the same formation as they are in a painting of Keats hanging nearby by his friend the artist Joseph Severn, in which he sits in the same room, bowed in thought over a book, with a bright green wilderness opening up out through the window before him.

Portrait of Keats, by Joseph Severn

Portrait of Keats, by Joseph Severn

Keats is not the only ghost you meet here. Elsewhere, you can picture Fanny Brawne, with her blue eyes, blue ribbons in her brown hair and her immaculate dresses in the latest Regency fashion. Fanny’s family had rented Charles Brown’s half of Wentworth Place during the summer of 1818 while Brown and Keats were on a walking tour of Scotland. When they came back in the autumn, the Brawnes moved out to a neighbouring property, but Keats soon met and became besotted with Fanny, whom he described as “beautiful, elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable and strange.”

Keats proposed to Fanny here in October 1819 and she said yes. But with Keats’ prospects as a struggling poet meaning their union was unlikely to gain the favour of Fanny’s mother, they hid their engagement. What fleeting, whispered words and deeds of love and passion took place between them within these walls remain secrets of the house…

The engagement ring Keats gave to Fanny, made of gold and set with a wine-coloured almandine stone, is on display in the room Fanny occupied. Though she went on to marry, have children and die in 1865 a dignified-looking Victorian lady, she wore the ring for the rest of her life and never revealed she was the love of Keats’ life. You can imagine her, in quiet and lonely moments in the years which followed, when Keats’ poetry began to escalate in popularity, treasuring the ring, re-reading the many love letters Keats wrote to her and mourning what might have been.

In what was once Keats’ bedroom, a small room on an upper floor, you can almost see him lying among the pale bed sheets, weak, tormented and sweating profusely as tuberculosis blights his body. After travelling back to Hampstead from London on the evening of 3rd February 1820, exposing himself to punishing winter wind and rain as he sat on the outside of an open carriage to save money, Keats had gone to bed feeling feverish. You’re compelled to squint hard at the sheets to discern any traces of the drops of blood which Keats reportedly coughed up on to his pillow that night, in terrified reaction to which he exclaimed to Charles Brown “I know the colour of that blood;—it is arterial blood; […] that drop of blood is my death-warrant;—I must die.”

Through small paintings on the wall just outside his bedroom of the moonlit sea seen from the deck of a ship, and of the warm and ancient Spanish Steps, you follow Keats’ journey down to Dover and then accompany him on his voyage to Rome where he came in November 1820 after a number of his close friends raised the funds to pay for his passage. They hoped the Mediterranean climate might restore his health. They were wrong.

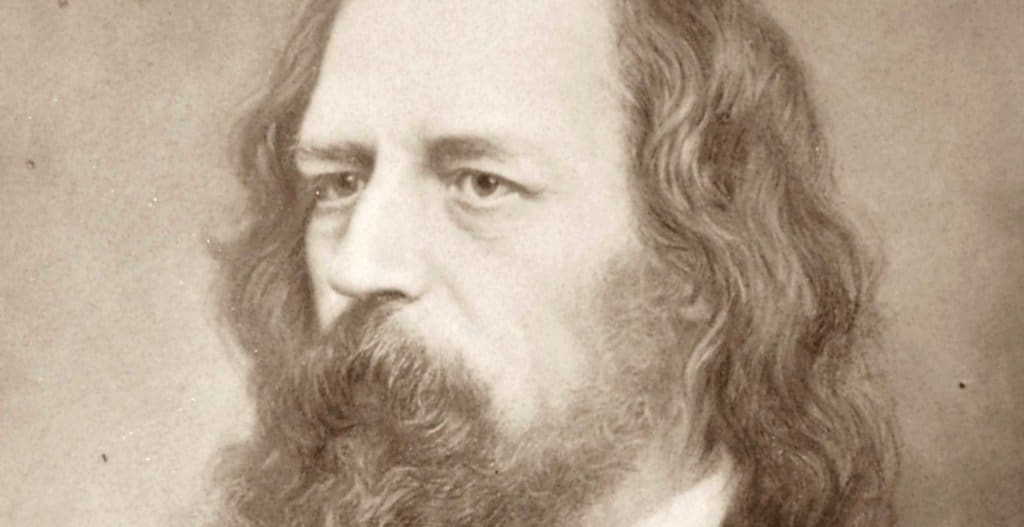

Portrait of Keats by William Hilton, after Joseph Severn

Portrait of Keats by William Hilton, after Joseph Severn

On the wall of his bedroom, just opposite what was once his bed, there hangs a framed pencil sketch of Keats’s head. He looks asleep and with soft light seeming to shine on his hair and closed eyes, Keats looks like an angel who has only just found peace.

In the quiet of the early hours of 28th January 1821, Joseph Severn sketched the likeness as his friend lay ill in bed before him. Still visible under the sketch, Severn has written “28 Janry 3 o’clock mng. Drawn to keep me awake – a deadly sweat was on him all this night.” Though now on the wall of Keats’ peaceful Hampstead bedroom, the sketch transports you back to that long night in 26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome where he spent his final days, weak and ill, and where, on 23rd February 1821, his enormous vision and poetic talent were lost to the world forever when he was still only 25 years old.

By Toby Farmiloe. Toby Farmiloe may physically live in London, but his heart and spirit reside firmly in the countryside and, more often than not, in a past century. Born and bred in East Sussex, he has always loved history.

Keats House, 10 Keats Grove, Hampstead, London NW3 2RR