2021 marked the 180th anniversary of Thomas Cook’s first step towards building the package holiday phenomenon. But ironically, wealth and social standing was the last thing on Thomas’ mind throughout his varied and illustrious career.

Thomas Cook circa 1880

Thomas Cook circa 1880

“We carried music with us, and music met us at Loughborough Station … and cheered us all along the line with the heartiest welcome … the whole affair being one which excited extraordinary interest, not only in the county of Leicester but throughout the whole country … All went off in the best style … and thus was struck the keynote of my excursions, and the social idea grew upon me.”

Thus wrote an exuberant Thomas Cook after his first organised day out for working class people of the Temperance Movement on 5th July 1841. A society devoted to encouraging others to give up alcohol and to try education instead, the Temperance members organised meetings, readings and family picnics as an alternative to hours spent in a pub. A member of the movement himself, Thomas decided to try something bigger to spread the word.

A fervent Baptist, Thomas believed in people helping themselves but recognised they could only do this if they were given the education and opportunity. At the same time, he surmised that travel educated a person by broadening their mind and firing the imagination, relaxing people and giving them hope. So he hoped to practise his ideas by arranging for 500 working class people to travel by train from Leicester to Loughborough to visit the Temperance quarterly meeting.

For most of his passengers, this was their first time on a train. Despite travelling Third Class in open air carriages, the whole trip was imbued with a holiday atmosphere, with villagers waving flags at the side of the tracks and Loughborough station decorated with banners, flags and props.

Mr Paget, a local dignitary, opened up his property Southfields for the day-trippers to use. White tablecloths were laid out under the shelter of trees and a typical English picnic of bread and ham and later crumpets and cake was consumed. Family games were arranged, and a cricket match enjoyed before minister after minister made rousing speeches accompanied by the band. It was the biggest teetotal party they had ever seen.

Thomas always wanted to help the poorer people in society as he had encountered his fair share of hardship. His father and stepfather both died when he was young and 10-year-old Thomas was apprenticed to a carpenter, working long hours and spending his free time in church. He grew up wanting a fairer society and a better democracy.

After Thomas married Marianne Mason in 1833, they opened up their home in Leicester to temperance travellers, as local inns were noisy, dirty, expensive and full of drunks. Leicester, like many towns in the north of England, had low life expectancy due to poor sanitation, a lack of freshwater reservoirs, hardly any drainage and an excess of factory pollution in the river Soar. It did a roaring trade in shoes and hosiery so there was the inevitable Victorian slum housing.

According to the Temperance Messenger magazine, Leicester was also home to 700 spirit shops, beer shops and pubs. It claimed the town had an above average amount of drunkards, prostitutes and cases of alcohol related diseases.

Fired up by the success of his first trip, Thomas set to organising more cheap Temperance days out for the working classes, volunteering his time and his own money to ensure success. Trips to Derby, Birmingham and Nottingham ensued, all underpinned by Thomas’ belief in feeding the soul with education and relaxation. In the summer of 1843, he took a crowd of Leicester teetotallers to the peaks of Derbyshire and parts of Yorkshire to breathe uncontaminated air.

Thomas tirelessly promoted his trips by printing and distributing leaflets and posters throughout the town. He gave promotional talks in the local Temperance Hall. In fact, although Thomas’s May Day trip wasn’t the first organised excursion by rail, it was the first to be promoted through the use of print material and proved a resounding success.

Thomas’ help for the working class didn’t stop at organising days out for them to try to forget their worries. He deeply abhorred alcohol and blamed it for the many problems the poor faced during the hungry Forties. He was a voracious anti-Corn Law protestor and orator, damning the use of cereal crops to make alcohol when hundreds of thousands of people were starving across the country.

He also promoted gardening, a new Victorian pastime, and bought potato seeds to distribute among the working class to encourage them to grow their own food. He even started printing a gardening magazine called The Cottage Gardener, covering the basics on how to grow vegetables and cultivate a cottage garden, although the copies no longer exist. He went onto help found the Leicester Allotment Society as another way of helping the poor to be fed but self-sufficient.

All this work came at the expense of Thomas’s own pocket and in August 1846 he filed for bankruptcy. Luckily, this no longer meant the shame and prison sentence it used to, and Thomas held onto his printing works and his home. This did teach him a valuable lesson though: he needed to make a hefty profit to continue helping the poor, and the best way to do this was to organise excursions for the middle classes.

Thomas had already decided to take the plunge in 1845, when he gathered up his courage and advertised his first commercial tour to Liverpool, with the opportunities to climb Mount Snowdon, explore Bangor and sail in a steamboat along the way, all backed up with his printed historical booklets. Despite tickets costing 10-15 shillings each, so clearly aimed at the middle class, demand for this trip far outstripped supply and another was planned a fortnight later. Thomas had found his niche. Cook’s Tours was born.

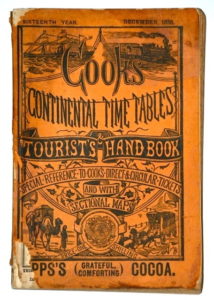

Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook

Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook

Although the company went on to become a package holiday phenomenon, Thomas never cared for gentrification. Large houses, country pursuits and members clubs passed him by as he continued to promote cheap travel for the masses.

In fact, he fell out with his son, as John Mason wanted to stop all non-profit making tours, but this went against everything Thomas stood for. He said of his son, “He does not like my mixing of missions with business; but he cannot deprive me of the pleasure I have had in the combination.”

Thomas’ last act of philanthropy was to build a pretty row of 14 memorial cottages and gardens in Melbourne, alongside a Baptist hall, a bakery and a laundry. Four flats were included for visiting Baptist ministers and their families, and a caretaker oversaw the upkeep.

When Thomas died on 18th July 1892, he had just £2731 in his bank.

William Gladstone summed up Thomas Cook in the Leicester Daily Post on the 20th July: “Thousands and thousands of the inhabitants of these islands who never would for a moment have passed beyond its shores have been able to go and return in safety and comfort, and with great enjoyment, great refreshment and great improvement to themselves.”

Written by Shona Parker. I blog about the social history behind the novels studied for GCSE English and drama at www.backinthedayof.co.uk. I include the type of social, political and economical paraphernalia which will pad out your knowledge and understanding, dispel your misgivings and make English history come alive!

Published: May 3rd, 2021.