Jane Austen’s appeal never fades. Maybe that’s why each year thousands of visitors continue to flock to Winchester in the county of Hampshire to get closer to the ‘real’ Jane Austen. Here we look at her life and legacy to examine why visiting the area is leaving so many Austen readers with a lasting sense of history, place and person.

Early days

‘Give a girl an education and introduce her properly to the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well.’ Jane Austen

Jane Austen was born on 16th December 1775 at Steventon Rectory in North Hampshire, where her parents had moved a year previously with her six older siblings – another child, Charles, was yet to be born – meaning the brood of children totalled eight in all.

Jane’s father, George Austen, was the rector of St Nicholas Church in the parish. Reverend Austen took in boys to tutor while his wife Cassandra (nee Leigh) (1731-1805) was a sociable, witty woman whom George had met while studying in Oxford. Cassandra was visiting her uncle, Theophilus Leigh, Master of Balliol College. When Cassandra left the city, George followed her to Bath and continued to court her until they got married on April 26th 1764, at the church of St. Swithin in Bath.

Although a close knit family, by today’s standards the household was subject to somewhat fluid arrangements regarding the care of offspring. As was customary for the gentry at the time, Jane’s parents sent her to be cared for by a farming neighbour, Elizabeth Littlewood, as an infant. Her older brother George, who is thought to have suffered from epilepsy, also lived away from the family estate. And the eldest child Edward was taken in by his father’s third cousin, Sir Thomas Knight, eventually inheriting Godmersham, and Chawton House close to the house in Chawton where Jane and Cassandra moved to with their mother. Although shocking by today’s standards, arrangements like these were normal for the time – the family was close and affectionate and recurring themes of family bonds and respectable rural living would play a strong part in Jane’s writing.

It was Jane’s older sister, Cassandra, who sketched the only first hand likeness of the author allowing us a glimpse of the novelist as a young woman. The tiny portrait, painted in 1810, bears lasting witness to the description of her by Sir Egerton Brydges who had visited at Steventon, ‘Her hair was dark brown and curled naturally, her large dark eyes were widely opened and expressive. She had clear brown skin and blushed so brightly and so readily.’

Education and early works

George Austen, known as ‘the handsome proctor’ at Balliol, was a reflective, literary man, who took pride in his children’s education. Most unusually for the period, he owned more than 500 books.

George Austen, known as ‘the handsome proctor’ at Balliol, was a reflective, literary man, who took pride in his children’s education. Most unusually for the period, he owned more than 500 books.

Again unusually, when Jane’s only sister Cassandra left for school in 1782, Jane missed her so acutely she followed – aged just seven. Their mother wrote of their bond, ‘If Cassandra’s head had been going to be cut off, Jane would have hers cut off too’. The two sisters attended schools in Oxford, Southampton and Reading. In Southampton the girls (and their cousin Jane Cooper) left the school when they caught a fever brought to the city by troops returning from abroad. Their cousin’s mother died and Jane also contracted the illness becoming very unwell but – luckily for literary posterity – survived.

The girls’ brief schooling was curtailed due to restraints upon the family’s finances and Jane returned to the rectory in 1787 and began writing a collection of poems, plays and short stories which she dedicated to friends and family. This, her ‘Juvenilia’ eventually encompassed three volumes and included First Impressions which later became Pride and Prejudice, and Elinor and Marianne, a first draft of Sense and Sensibility.

Selected works from the three volumes are available to browse online and A History of England, perhaps the most celebrated of her early works, can be viewed on the British Library website. Even in this, one of Austen’s earliest texts, the reader glimpses the wit that was to come. The prose is peppered with phrases illustrating her flair for detached, literary anticlimax: ‘Lord Cobham was burnt alive, but I forget what for.’

Steventon today: what to see

Other than a towering lime tree, planted by Jane’s brother James and a clump of nettles that marks the spot where the family well used to stand, nothing remains at the site of the rectory other than the rural tranquillity that was perhaps as central an element of Austen’s creativity as the society of her day.

At St Nicholas Church there is a bronze plaque dedicated to the writer and, set into the wall to the left of the pulpit, is a small collection of finds from the site of the Austen’s rectory. In the churchyard, you can see her elder brother’s grave, along with those of other relatives. The 1000-year old yew, which used to house the key in the time of the Austens, still yields berries, its secret, central hollow intact.

The dancing years

Coming from a respectable family associated with the church, Jane and her sister Cassandra occupied a social stratum bracketed as ‘low gentry’.

The well spoken girls enjoyed a busy round of dances and house visits, mingling with the higher echelons of local Georgian society in the great houses dotted throughout the rolling green countryside.

As well as spending time with the family friend Madam Lefroy, who lived at Ashe Rectory, we know that Jane and Cassandra came into contact with the infamous Boltons of Hackwood Park, (Jane dryly comments after meeting the illegitimate daughter of Lord Bolton in the Bath Assembly Rooms that she was ‘much improved with a wig’); the Hansons of Farleigh House; and the Dorchesters of Kempshott Park where Jane attended a New Year’s ball in 1800.

Jane’s keen observation of the manners and morals of her extended social network was to give rise to her infamous plotlines revolving around unsuitable suitors and social position – she started draftingPride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility and Northanger Abbey whilst living at the rectory.

Portsmouth

Jane’s brothers Charles and Frank, were both serving officers in the Royal Navy in Portsmouth and it is likely that she could have visited them – which may explain the references to the city in Mansfield Park.

In the novel she portrays the old city convincingly, touching on the squalor of its poverty. The naval dockyard she describes in Mansfield Park is now a sports field in neighbouring Portsea but the city still features the Georgian architecture which marks its development as a suburb serving the naval personnel who guarded the once heavy coastal fortifications.

Southampton

Jane, her mother and sister Cassandra moved to Southampton upon the death of her father in 1805. Jane found living in a city a challenge after her country childhood and we know that the women spent much time out of doors – promenading along the city walls and taking excursions to the River Itchen and the ruins of Netley Abbey. Surviving correspondence also tells us that the three women travelled up the Beaulieu River passing Buckler’s Hard, an 18th century shipbuilding village and Beaulieu Abbey.

Jane Austen’s House and Museum, Chawton

From 1809 until 1817 Jane lived in Chawton village near Alton with her mother, sister and their friend Martha Lloyd. Restored to the rural Hampshire she loved, Jane turned again to writing and it was here that she produced her greatest works, revising previous drafts and writing Mansfield Park,Emma and Persuasion in their entirety.

A few lines of poetry penned upon her arrival hint of her delight in the return to a more rural living upon their return to Chawton:

‘Our Chawton home – how much we find

Already in it, to our mind,

And how convinced that when complete

It will all other Houses beat,

That ever have been made or mended,

With rooms concise or rooms distended.’

Today, the approach to Chawton is not so changed by progress as to be unrecognisable from what it was in Jane Austen’s day, with thatched cottages remaining. And the risk of flooding was a fact of life in eighteenth century Hampshire too, Jane bemoans in March 1816… ‘Our Pond is brim full and our roads are dirty and our walls are damp, and we sit wishing every bad day may be the last’.

A museum to Jane’s life, the house in which Jane lived so happily now showcases Austen family portraits and touching memorabilia such as the handkerchief she embroidered for her sister, original manuscripts and a bookcase containing first editions of her novels. Visitors can stand behind the modest occasional table at which Austen wrote to admire the peaceful garden cultivated to feature 18th century plants.

Although there were adequate bedrooms for the sisters to have their own rooms, Jane and Cassandra chose to share a room, as they had done at Steventon. Jane rose early and practised the piano and make breakfast. We know that she was in charge of the sugar, tea, and wine stores.

Also in the village is Jane’s brother Edward’s home – now Chawton House Library. The collection of women’s writing from 1600 to 1830 stored here is accessible to visitors by prior arrangement.

Winchester

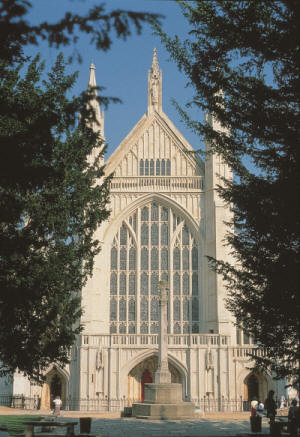

In 1817, suffering from a kidney disorder, Jane Austen came to Winchester to be close to her physician. Jane only lived a few weeks in her house in College Street but continued to write – penning a short poem called Venta which was about the Winchester Races, traditionally held on St Swithin’s Day. She died – only 41 years old – on July 18th, 1817 and was laid to rest in the ‘long old solemnly grey and lovely shape of the cathedral’. As a woman, the heartbroken Cassandra was not able to attend the funeral, despite losing a sister she described as ‘the sun of my life’. The original memorial stone over Jane’s tomb makes no reference to her literary achievements, so a brass plaque was added in 1872 to redress this. In 1900 a stained glass memorial window, funded by public subscription, was erected in her memory.

Today, the City Museum in Winchester displays a small collection of Austen memorabilia, including a handwritten poem which she wrote while living the city.

© Winchester City Council, 2011

External Links:

Winchester’s Austen trail (UK) (links to much of the material and information mentioned in the article above can be found on this site).

The Jane Austen Society of the United Kingdom.