In Britain in the late 19th century and early 20th century, there were nearly as many pawnbrokers as public houses, lending money on anything from bed linen and cutlery to father’s ‘Sunday best’ suit.

Hanging over the lives of the poor was the fear of the workhouse. They would do anything to avoid it, even if it meant pawning their belongings to gain some cash temporarily. Clothes, shoes and even wedding rings would be pawned to be redeemed later if the owner’s circumstances improved.

“Half a pound of tuppenny rice,

Half a pound of treacle,

That’s the way the money goes,

Pop goes the weasel!”

This song from around 1850 is reputedly about pawning (“popping”) a coat or “weasel” (from the rhyming slang “weasel and stoat”) in order to get money to buy simple foodstuffs.

Eventide: A Scene in the Westminster Union (workhouse), 1878, by Sir Hubert von Herkomer

Pawnbrokers were easily identified by their signs of three golden balls, a symbol of St Nicholas who, according to legend, had saved three young girls from destitution by loaning them each a bag of gold so they could get married.

So how does pawning work? An item is taken to the pawnbroker who lends an amount of money to the owner of the object. The item is held by the pawnbroker for a certain length of time. If the owner returns within the agreed time limit and pays back the money lent plus an agreed amount of interest, the item is returned. If the loan is not paid within the time period, the pawned item will be offered for sale by the pawnbroker.

The word pawn comes from the Latin word pignus or ‘pledge’, and the items being pawned to the broker are called pledges or pawns. Pawnbrokers came to England with the Normans and the settlement of Jews in England. Ostracized from most professions, they had been pushed into unpopular occupations such as money lending and pawnbrokering which, as interest was charged on the loan, was condemned by Christians.

Tensions soon arose between creditors and debtors and these tensions, along with the social, political and religious differences, added to the rise in anti Jewish feeling. It also didn’t help that some Jews had become incredibly wealthy: Aaron of Lincoln is believed to have been the wealthiest man in 12th century England, even wealthier than the king.

In England, this tension resulted in the terrible massacres of Jews at London and York by departing Crusaders and crowds of debtors in 1189 and 1190. Today, there is a plaque at Clifford’s Tower in York which states: “On the night of Friday 16 March 1190 some 150 Jews and Jewesses of York having sought protection in the Royal Castle on this site from a mob incited by Richard Malebisse and others, chose to die at each other’s hands rather than renounce their faith.”

Clifford’s Tower, York

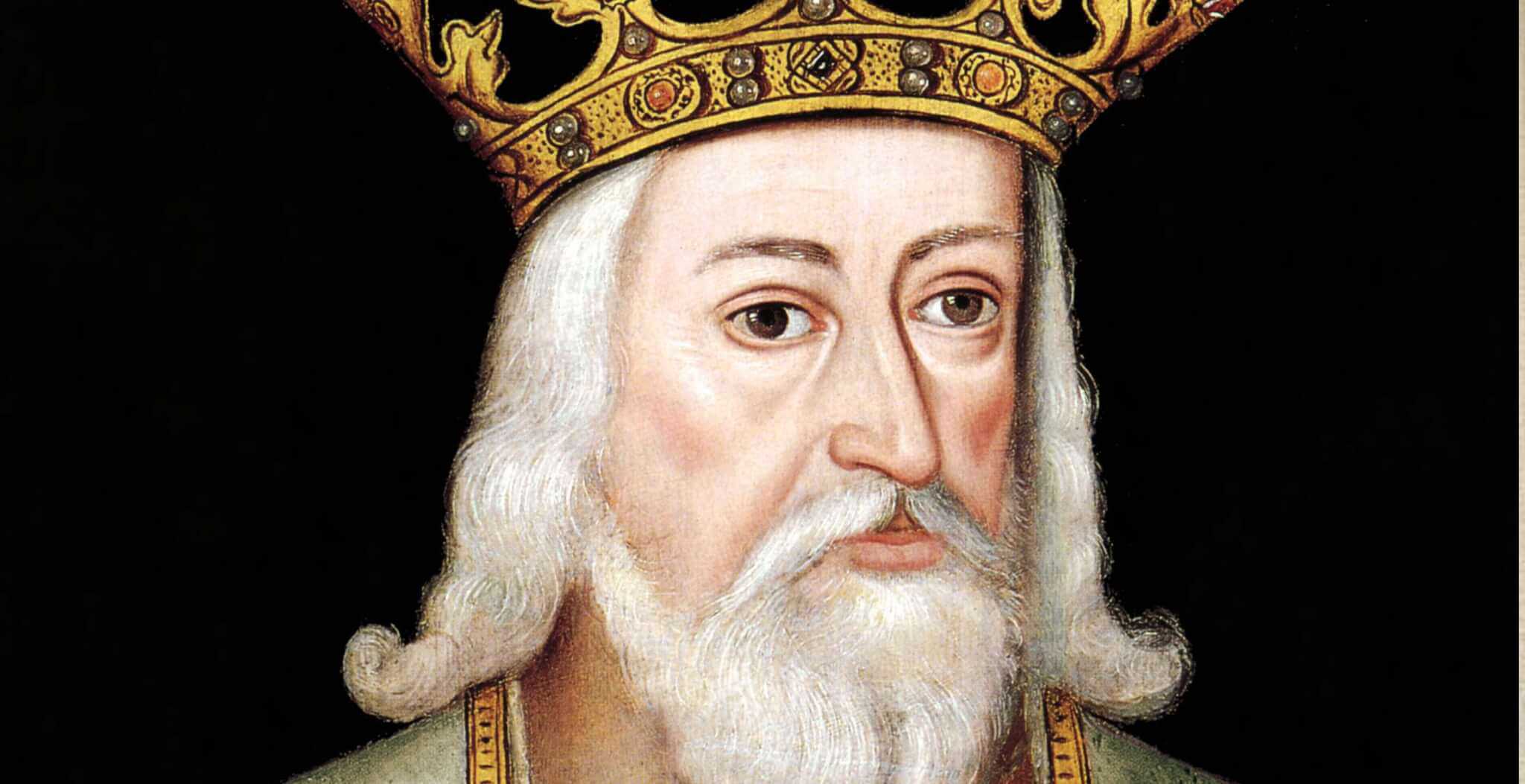

In an attempt to acquire the great wealth of the Jews, in 1275 King Edward I passed the Statute of Jewry which made usury illegal. Usury is the lending of money whilst charging interest at an exorbitant or illegally high rate. Scores of English Jews were arrested, 300 were hanged and their property seized by the Crown. In 1290, all Jews were expelled from England. Usury was used as the official reason for the Edict of Expulsion.

However this was not the end of the pawnbroker: in 1361 the Bishop of London bequeathed 1000 silver marks for the establishment of a free pawnshop. And it was not just ordinary people who had need of a pawnbroker: in 1338, Edward III pawned his jewels to raise money for his war with France, the Hundred Years’ War.

The rather dubious image of pawnbroking has changed over the past thirty years or so. The 1980s credit boom and the recent recession have resulted in many people preferring this convenient form of High Street borrowing to a loan from the bank or a payday loan. The resurgence of pawnbroking is even reflected in the ITV soap ‘Coronation Street’ where the new shop on the Street is Barlow’s Buys – a pawn shop.