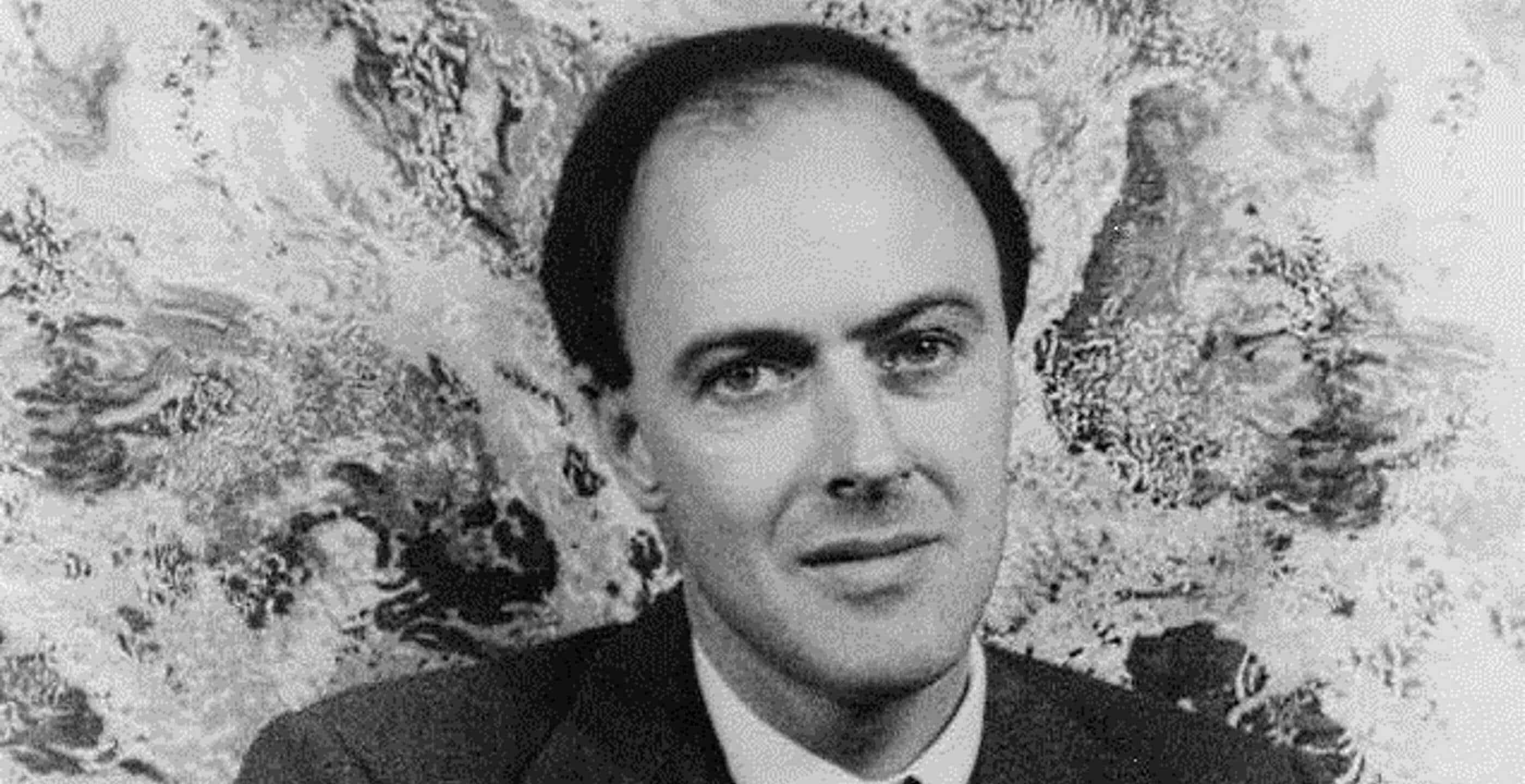

He once said it was the head injury he sustained and the resulting six weeks of blindness after crashing his World War II 3 Gloster Gladiator airplane in the Libyan desert, that changed something inside him.

That incident, Roald Dahl claimed, was what ignited an imagination that would propel him into the annals as one of the world’s greatest children’s writers, creating such classics as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, and James and the Giant Peach. Along with being one of the most successful writers of juvenile fiction, he was also an adventurer and a prolific golfer.

Dahl loved playing golf so much that his clubs were never far from his side, no matter where he was on the planet. He first swung a golf club at the age of nine and the feeling grabbed hold of him with the same energy and enthusiasm as his ideas for stories. He would never be much better than an average golfer in his lifetime but he played with a passion each and every time he stepped on a course, it was as if he was playing on Sunday at the Open Championship.

After primary school, a poor student at that, he decided to forgo college and travelled to Newfoundland with a group of students to explore the uncharted island. His time in the bush only intensified his desire for adventure and to travel.

Upon returning to England he landed a job with Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company and was stuck in an office, much to his discontent. Life in the office, shuffling paper and wearing grey suits wasn’t for him. The one aspect of the job he did like was playing in the company golf tournament; in 1936 he finished runner-up and had his name published in the Shell Magazine. He was very proud of this achievement.

He spent two miserable years in the London office, thirsting for adventure and the opportunity to travel and explore the world. When a few positions abroad opened, he applied for them at one of the company’s outposts either in Africa or the Far East. As luck would have it, he was granted a post in Africa, supplying oil to customers primarily for farm equipment and aviation. In 1933 Africa was still very much a blank space on the map and considered the Dark Continent.

Much like a Joseph Conrad novel, he was stepping into the unknown. Stories of wild beasts and hostile warring native tribes, vanishing coteries of explorers and disease were common themes hastily scribbled in diaries. Dahl was fairly conscious of what he was getting into, but it was just the buffet of danger and risk that would satisfy an unquenchable appetite for the high-octane exploits he craved.

Back then most people didn’t make quick travel by air. Instead it was a three and four week trip by way of ships. Without instruments to detect approaching weather of heavy seas and storms, ships just had to ride them out.

For Dahl, sailing journeys sparked his imagination and he liked to say in older age how kids today don’t understand how wonderful it was to be stuck on a ship for weeks travelling to your destination. Dr. Seuss, famed writer of the Cat in the Hat, wrote his first book on a ship in the middle of the ocean during a storm while sipping a glass of vodka.

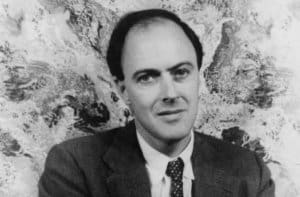

Dar-es-Salaam

Dar-es-Salaam

Africa was everything that Roald Dahl imagined and more. When the ship pulled into Dar-es-Salaam harbour he gazed out of the porthole at the view and said it was, “photographed on my mind ever since.” He remembers it well: “Over to one side lay the tiny town of Dar-es-Salaam, the houses white and yellow and pink, and among the houses I could see a narrow church steeple and a domed mosque and along the waterfront there was a line of acacia trees splashed with scarlet flowers. A fleet of canoes was rowing out to take us ashore and the black-skinned rowers were chanting weird songs in time with their rowing…to me it was all wonderful and beautiful and exciting.”

Years later in his autobiography Going Solo about his time in Africa, Dahl would reflect, “I loved it all. There were no furled umbrellas, no bowler hats, no somber grey suits—all common sights in England at the time, and I never once had to get on a train or a bus.” Not to mention there were also wonderful rounds of golf to be played.

Dahl teed up in Egypt in the shadow of the great pyramids, in the northwest of the continent and coastal marshes of Sierra Leone on the Atlantic. He would putt for birdies in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Kenya, France, America and anywhere else he could get a tee time. During a few rounds in Dar es Salaam he and his playing partners stumbled upon cobras, and in Lagos they were pelted with unripe mangos by a contingent of monkeys.

One morning he was standing in his bathroom shaving. Out of the window he could see the shamba-boy servant, Salimu, raking the gravel of the driveway. Just then movement caught Dahl’s eye. It was a highly poisonous black mamba snake heading straight for Salimu. Dahl would describe the snake as being six feet long and as thick as his arm. He leaned out the window and shouted to the boy in Swahili “Salimu! Angalia nyoka kubwa! Nyuma wewe! Upesi upesi!” “Beware huge snake! Behind you! Quickly!”

The snake was moving at the speed of an agile race dog. The boy spun around and crouched holding the rake at the height of his shoulders, stiff, alert, ready for the confrontation. He eyed the charging snake in khaki pants and bare feet. The black mamba is the only snake that has no fear of man and will attack without provocation. Its head was up and ready to strike and all Dahl could do was lean out the window and wait and watch as horrible images of what might occur raced through his mind.

When the reptilian monster was no more than five feet from Salimu, the boy slammed the rake down on its back, trapping it. The snake fought and tried to attack. Completely naked, Dahl ran down the stairs. By the front door were his golf clubs. He grabbed a club and exited the house. Dahl was standing in the driveway, without clothes, gripping his golf club. A few paces away stood Salimu with the trapped snake. It was injured and weakened and the boy was able to kill the mamba with a blow to the head using the metal prongs of the heavy rake.

During his time in Africa Dahl was surrounded by wild animals, including lions, rhinos, and hyenas, but none of them frightened him as much as the snakes.

Also while in Africa, World War II began. Dahl enlisted as a special constable. He was put in charge of a company of native soldiers who hunted fleeing Germans nationals, in support of the war, trying to return to Germany. The Germans they caught were arrested and transported to internment camps.

One day Dahl and a few men were at a roadblock when about 50 cars of Germans approached. Dahl and his unit blocked the road with trucks. A bald German, the leader, exited the lead car. About 70 or so other men exited cars within the caravan and made a semi-circle behind the leader. He looked hard at Dahl and angrily said to his people, “We will move the trucks.”

Dahl said, “Hold it right there. We are ordered to stop you from leaving. If you don’t comply we will be forced to shoot.”

“Who will shoot?” The leader said in a thick German accent. He then produced a large lugar pistol from the waistband of his khaki pants. The men behind him also produced similar lugers. The leader pointed his luger at Dahl’s chest. Dahl would say later, “I had seen this sort of thing done a thousand times in the cinema, but it was a very different thing in real life. I was properly frightened.”

Dahl put his hands above his head. The man smiled, thinking that Dahl was surrendering, when gunshots rang out. The bullets whizzed over their heads startling everyone including the Germans. One of the guns that opened fire was a machine gun that had come from Dahl’s men. The Germans then knew they were outgunned. Dahl was again in control and told the Germans they couldn’t pass. He knew that their plan was to go to Portuguese East Africa, sail back to Germany and become soldiers. Dahl’s orders were to prevent that from occurring but the leader aggressively grabbed Dahl’s arm and put the pistol to his chest. He then screamed in Swahili at Dahl’s native soldiers that their officer would be killed in cold blood if they didn’t clear the road. Just then, unseen from the wood line, a sniper took a single shot that struck the leader in the face, killing him instantly. “It was a horrible sight,” Dahl recalls. “The luger dropped to the ground and the leader fell dead beside it.” The rest of the Germans surrendered and were transported to a prison camp.

Gloster Gladiator

Gloster Gladiator

Later, Dahl signed up to become a pilot and traveled to Iraq for training. After six months of training he passed the exams and flight tests. He returned to Africa, to Egypt where he would take control of his own airplane, a 3 Gloster Gladiator. Dahl was given orders, by the RAF, to fly from Abu Suweir airfield in Egypt to the Western Desert of Libya, to rendezvous with his 80 squadron, where they would see real action. Dahl would never see this action. Having no radio and no navigational assistance except a map strapped to his knee, he was unable to locate the airstrip and crash landed in the desert, striking a large bolder.

He sustained a fractured skull and numerous other injuries. The plane was completely destroyed by the impact and the inferno that followed. As the plane ignited Dahl vaguely remembers hearing a whoosh sound as the fuel tank on the right wing caught fire. After hearing a second whoosh the tank on the starboard side exploded. He said he felt no pain and because of his head injury just wanted to go to sleep at that moment. The heat from the fire, however, was becoming so intense that he unstrapped himself from the cockpit and began dragging himself away from the aircraft. By now darkness had fallen over the desert. The location of his crash, he learned later, had been in “no man’s land,” right between the British and Italian lines. Both sides had seen his plane burning in the distance. Luckily for Dahl three members of the RAF made it to him first that night. He was found semi-conscious with terrible injuries and his overalls burned by the flames. He was dragged back to the British lines without a stretcher.

For six weeks he suffered blindness due to massive swelling. The recovery was slow, but he fully healed and was sent back to war. It was in Greece flying a Hawker Hurricane patrolling the airspace that he would shoot down his first enemy plane. During this time he had been suffering from headaches that continued to worsen. Soon he began blacking out and it was determined that he was unfit to fly. That was the end of his time in air. He had spent a total of 32 days as a combat fighter pilot.

After the war ended, Dahl took a job working for British Government in Washington D.C. as a public speaker trying to champion Americans in favour of the British war effort. It was a job he loathed. He was also a spy with MI6 and worked alongside another spy, Ian Fleming, who would go on to create the hit James Bond 007 series. A third spy in their network was future advertising tycoon David Ogilvy.

While in Washington, Dahl was approached by a colleague who worked for a newspaper. He asked Dahl to send him a written account of his wartime experiences so he could put it in a story. Instead, Dahl wrote his own experiences and the newspaper paid him three hundred dollars for the story.

After that he continued to write stories for various publications. One of his stories, published in 1943 in Cosmopolitan magazine, was a tale called Gremlin Law about little creatures called Gremlins that pilots and mechanics blamed for mysterious problems with their aircraft. It became a popular read.

It was that story that got him inadvertently discovered. Walt Disney happened to read it and decided that he wanted to turn it into a children’s film called Gremlins. He invited Dahl to Warner Brother’s studios and set him up with half a dozen artists to bring the story to life.

The movie, however, was never produced because the company felt that public interest in wartime stories was decreasing, Disney went on to publish the story as a book instead. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt read the story to her grandchildren and was so charmed by Dahl that she invited him to dinner at the White House. The two became lifelong friends.

And for Roald Dahl, the rest is history. He began churning out some of the most loved and recognized children’s classics to ever reach print and film.

Later in life, after a day writing in Gipsy House, his tiny writing hut that sat in the back of his garden, he would grab his golf clubs and beat balls around his property for hours. Whenever a golf tournament was on television Roald would be watching. He loved watching sports and loved watching golf. He considered golf to be “One of the loveliest games in the world.”

Dahl passed away in 1990. His legacy as one of the world’s greatest children’s writers will live on forever.

By Greg Evans. I am a history buff and journalist. My work has appeared in numerous publications around world. I especially enjoy writing biographical sketches about interesting people.