Who are the British? Do they really drink tea, eat roast beef and Yorkshire pudding and never leave home without an umbrella?

This is how we introduce the Culture section of our on-line magazine and for many, this is quite true: we do love a roast dinner on Sunday, we do drink a lot of tea, and an umbrella is a very sensible accessory! Our weather changes so often that you can sometimes experience all four seasons in one day, and so most conversations open with a discussion on it.

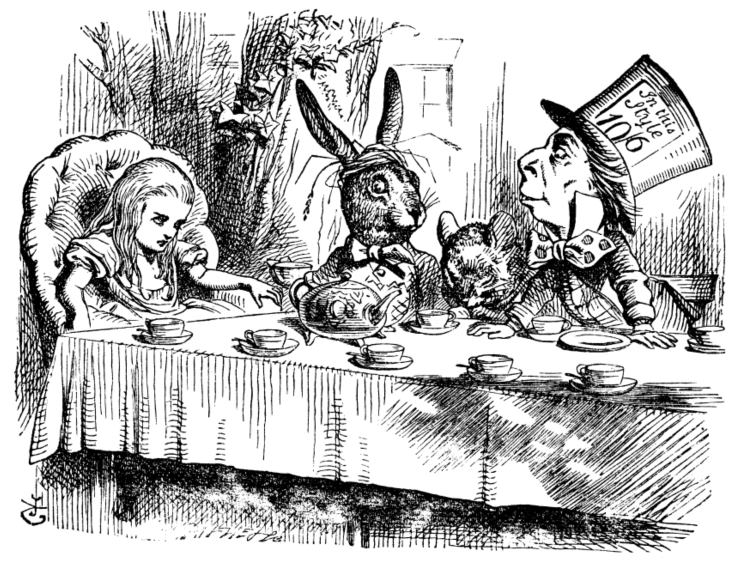

As for tea, this is an integal part of the rich tapestry of British life. After a shock, sweet tea is offered to make you feel better. Problems are shared and halved over a cup of tea. Afternoon tea is a British institution, so much so it appears in our literature.

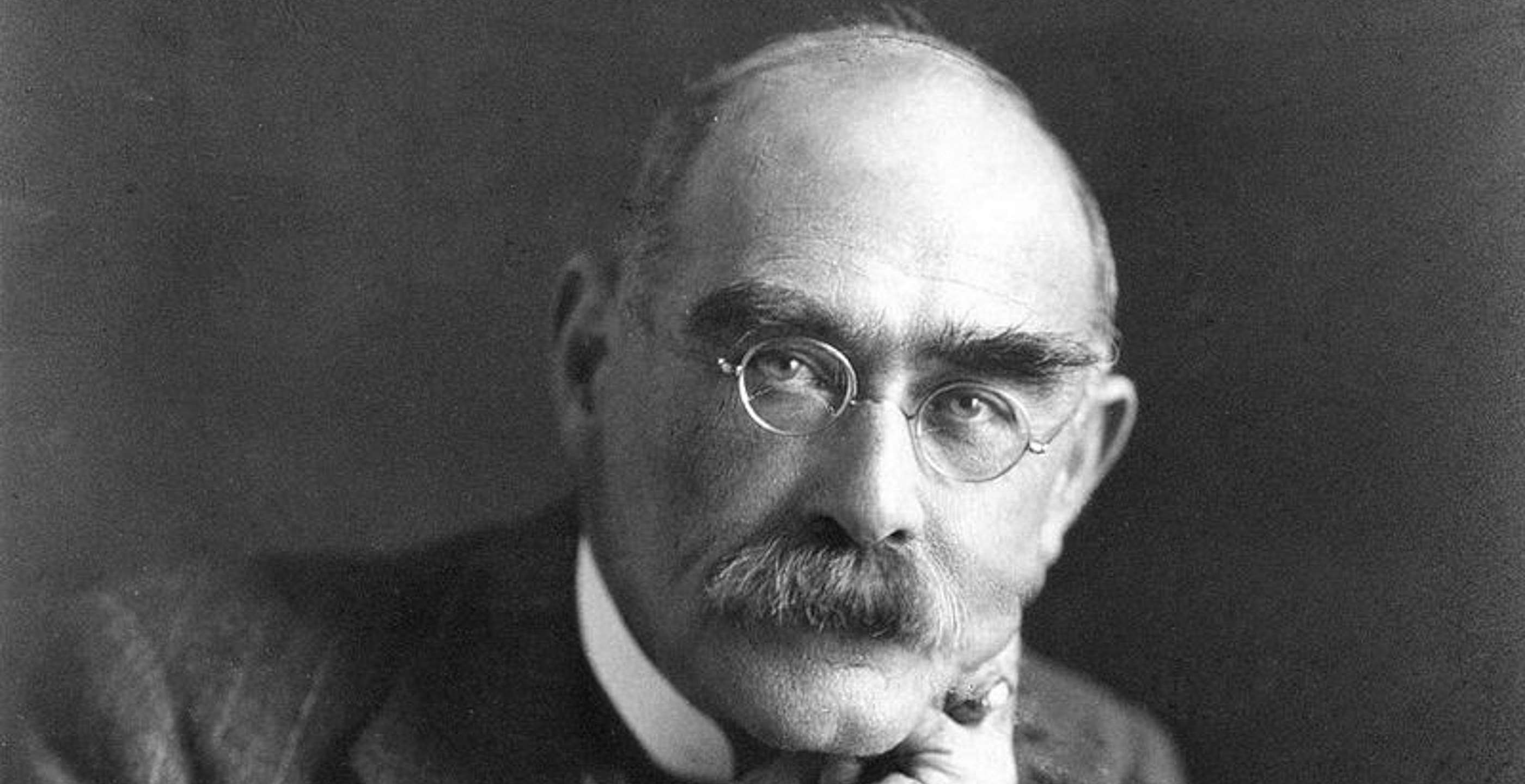

But there is much more to the British psyche. Take Rudyard Kipling’s poem first published in 1911, ‘The Norman and the Saxon’:

“My son,” said the Norman Baron, “I am dying, and you will be heir

To all the broad acres in England that William gave me for share

When he conquered the Saxon at Hastings, and a nice little handful it is.

But before you go over to rule it I want you to understand this:

“The Saxon is not like us Normans. His manners are not so polite.

But he never means anything serious till he talks about justice and right.

When he stands like an ox in the furrow – with his sullen set eyes on your own,

And grumbles, ‘This isn’t fair dealing,’ my son, leave the Saxon alone.

“You can horsewhip your Gascony archers, or torture your Picardy spears;

But don’t try that game on the Saxon; you’ll have the whole brood round your ears.

From the richest old Thane in the county to the poorest chained serf in the field,

They’ll be at you and on you like hornets, and, if you are wise, you will yield.

“But first you must master their language, their dialect, proverbs and songs.

Don’t trust any clerk to interpret when they come with the tale of their wrongs.

Let them know that you know what they’re saying; let them feel that you know what to say.

Yes, even when you want to go hunting, hear ’em out if it takes you all day.

They’ll drink every hour of the daylight and poach every hour of the dark.

It’s the sport not the rabbits they’re after (we’ve plenty of game in the park).

Don’t hang them or cut off their fingers. That’s wasteful as well as unkind,

For a hard-bitten, South-country poacher makes the best man-at-arms you can find.

“Appear with your wife and the children at their weddings and funerals and feasts.

Be polite but not friendly to Bishops; be good to all poor parish priests.

Say ‘we,’ ‘us’ and ‘ours’ when you’re talking, instead of ‘you fellows’ and ‘I.’

Don’t ride over seeds; keep your temper; and never you tell ’em a lie!”

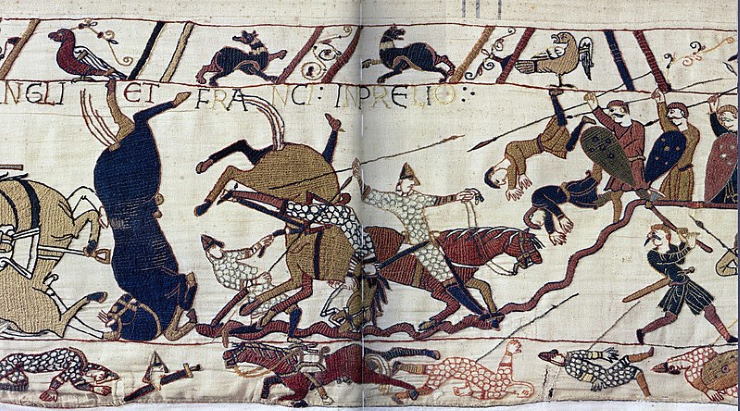

This poem is set in the year 1100 after the Norman invasion of England in 1066, when Norman barons were imposed as overlords over the native Anglo-Saxons. This is a dying Norman lord’s instructions to his arrogant son of how to get along with the Saxons after he has gone.

In the second paragraph Kipling refers to perhaps the strongest traits running through the average Brit: those of justice and fairness:

“But he never means anything serious till he talks about justice and right.

When he stands like an ox in the furrow – with his sullen set eyes on your own,

And grumbles, ‘This isn’t fair dealing,’ my son, leave the Saxon alone.”

The British do indeed hate unfairness: “it’s just not cricket!” we cry.

Talking about our national game – no, not soccer – Henry Newbolt’s powerful poem Vitai Lampada, written in 1892, is a must-read to understand the values for men that Victorian Britain held highly, those of gentlemanly conduct and ‘stiff upper-lip’. “Play up and play the game!” is the cry throughout the poem, which takes us from the school cricket field to an unnamed battlefield somewhere in the British Empire. At the centre of the poem is an inherent belief in fairness, courage and duty and it shows eerie parallels between the cricket field and the battlefield.

So here are two poems written over a century ago that give us an idea of traditional British values and traits. The British love fair play and for things to be fair: injustices are felt keenly. There is a strong sense of honour, loyalty and duty: to oneself, to one’s family and friends, and ultimately to King and country.

And we can queue. Boy can the Brits queue. This has its origins in our sense of fairness: it is unfair to jump the queue, unfair to those who have ‘played the game’ and stood in line. We queued for days to pay our respects to the late Queen Elizabeth in 2022: The Queue, as it became known, even had a daily weather forecast all of its own! To quote George Mikes, “An Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.”

The British also love to apologise: “Sorry” is probably the most over-used word in the average Brit’s vocabulary. We will apologise for anything, sometimes even things we have not done. If someone bumps into a British person, they will say sorry even though they are not at fault. If they should accidently blunder into a door, they will – almost without exception – apologise to the door. A rather eccentric thing to do, you might say.

And yes, you would be right. We Brits are eccentric.

Just take the London Olympics opening ceremony in 2012 as an example. A wonderful introduction to Britain and the British, through British history, literature and music. And with a large dose of eccentricity.

Witty, wacky and quintessentially British, according to the foreign press. Who can forget James Bond 007 apparently parachuting into the stadium with her late majesty, Queen Elizabeth II? Or hundreds of children bouncing on beds while celebrating the NHS? Or Mr Bean playing the iconic theme ‘Chariots of Fire’ with the London Symphony Orchestra?

Brits have a great sense of humour. We love slapstick and innuendo – the Carry On films for example. We love poking fun at ourselves, like the pretentious Hyacinth Bucket (“Bouquet”) in ‘Keeping Up Appearances’.

Produced as part of the Platinum Jubilee celebrations in 2022, the short film of Queen Elizabeth and Paddington Bear having tea – “Ma’amalade sandwich your Majesty?” – is an excellent example of our love of the ridiculous. And reminds us of our late monarch’s great sense of humour. God bless you Ma’am.

By Ellen Castelow.

Published: 23rd August 2024.