Monuments and statues to the events and figureheads of imperial history became battlegrounds in the ongoing culture wars for the past, present and future of British society during 2020. One such monument to the Royal Marines was erected next to Admiralty Arch on the Mall in 1903. One of the bronze reliefs on the memorial is dedicated to the Marines who died defending the Peking (Beijing) International Legations (Settlement) in 1900 against Chinese anti-foreign fighters, colloquially dubbed ‘Boxers’ in the British press. The Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) and much of Britain’s past and present involvement with China is often a subject of mystery and mistranslation.

In this case the recent wave of well-intentioned iconoclasm will not in itself help us publicly engage with the legacies of Britain’s East Asian Empire, but it does offer a gateway. If we look past the stone and granite and instead to how the crises of empire registered in the vibrant yet ephemeral atmosphere of popular theatre and entertainment, we gain a greater window into the fashions which saturated and reflected the society of Imperial Britain at the dawn of Edwardian period. The article focuses on one play called ‘Sen Yamen’ performed on the provincial stage at the Rugby Theatre Royal in October 1901 which fused comedy with colonialism to create a bizarre angle on the Chinese rebels.

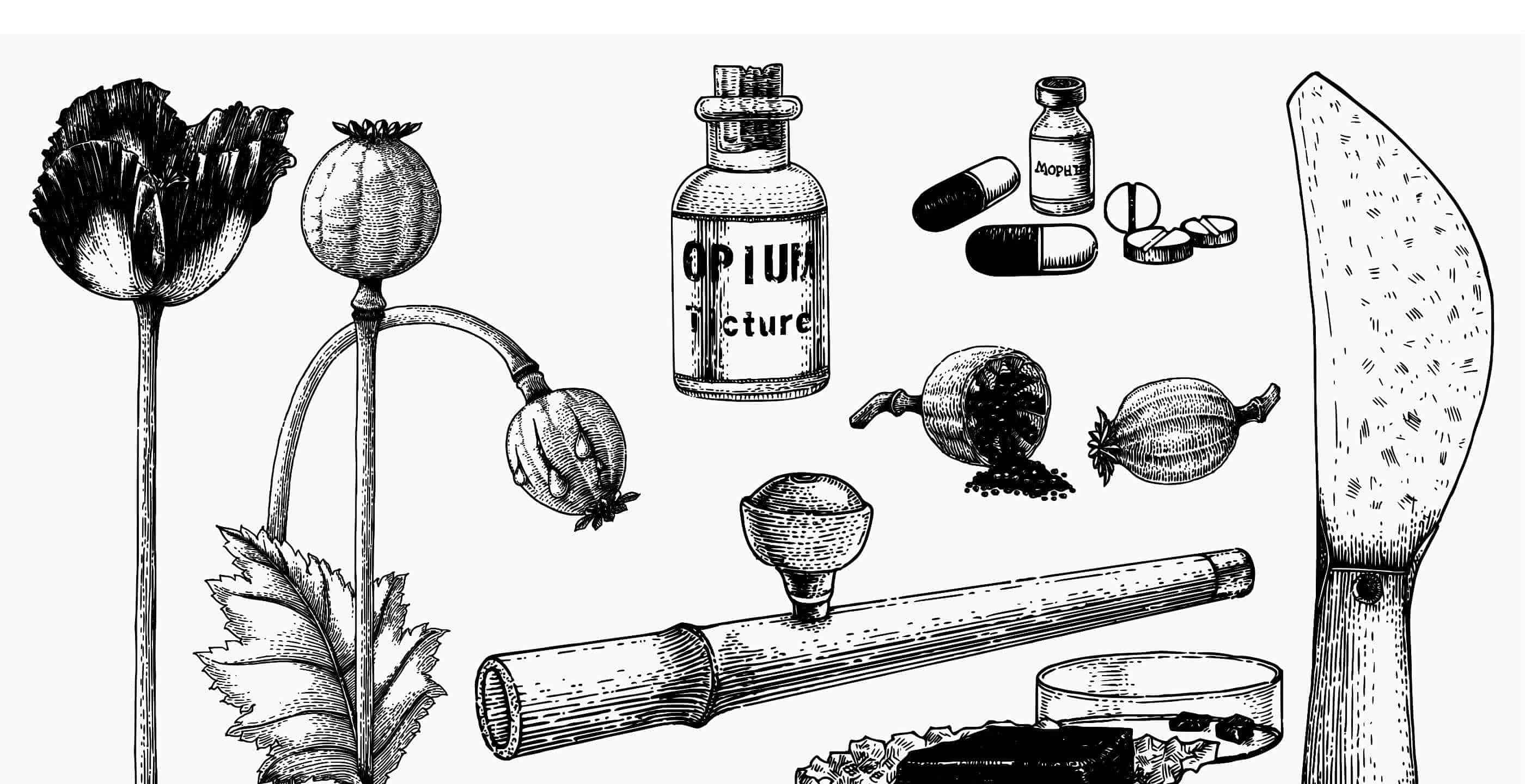

After the First Opium Wars (1839-42) against the Qing Empire and Treaty of Nanjing (1845), Britain and other foreign empires steadily acquired enclaves of economic control and extraterritorial rights in coastal cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Nanjing. These were collectively known as the Treaty Ports after the unequal access agreements the Qing were compelled to sign.

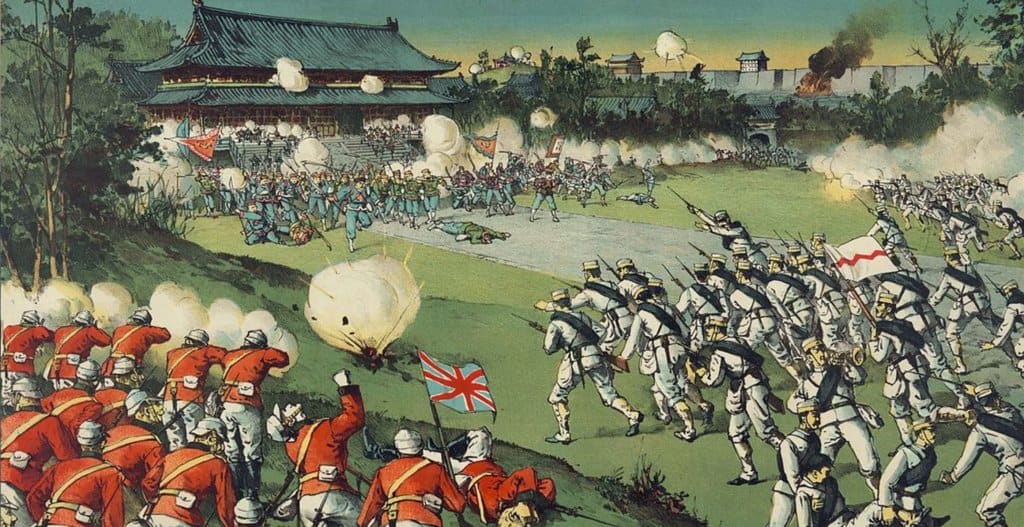

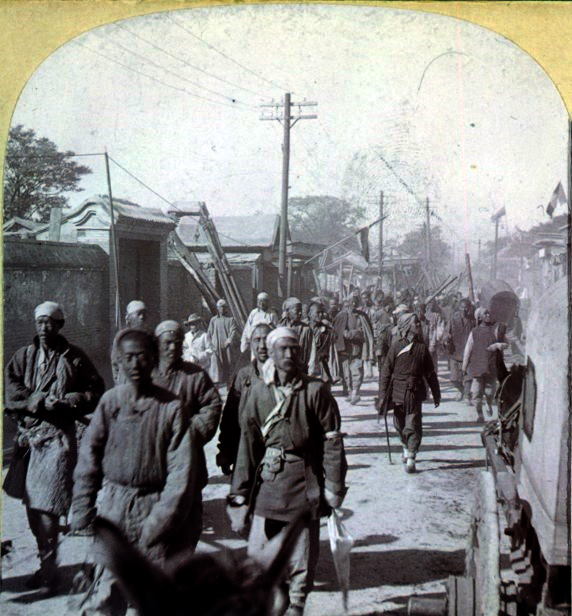

The Boxer Rebellion was the fourth in a long line of conflicts whereby British power in China was contested. A movement in Shandong, North Western China proliferated known as ‘Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists’. Deeply anti-Christian, these martial arts fighting groups attacks on Western and Chinese Christians snowballed into an orgy of xenophobic violence and besiegement of Peking (June-August 1900). An eight-power reaction force was deployed and took revenge with punitive expeditions and a heavy indemnity exacted on the Qing in the protocol of 1901.

The siege gripped the British press with extreme anxiety and xenophobic outrage. The Boxers themselves gained notoriety as a ‘yellow peril’ threatening the fabric of a British Christian world order. This fed a glut of cartoons, memoirs and plays from British publishers and protagonists. Even a short film, a dramatization called ‘Attack on the China Mission’ was shown in Hove, England on 17 November 1900.

However, some British producers reacted very differently, and Racial-Imperial geo-politics collided with mass market entertainment and fanciful chinoiserie to produce some bizarre results.

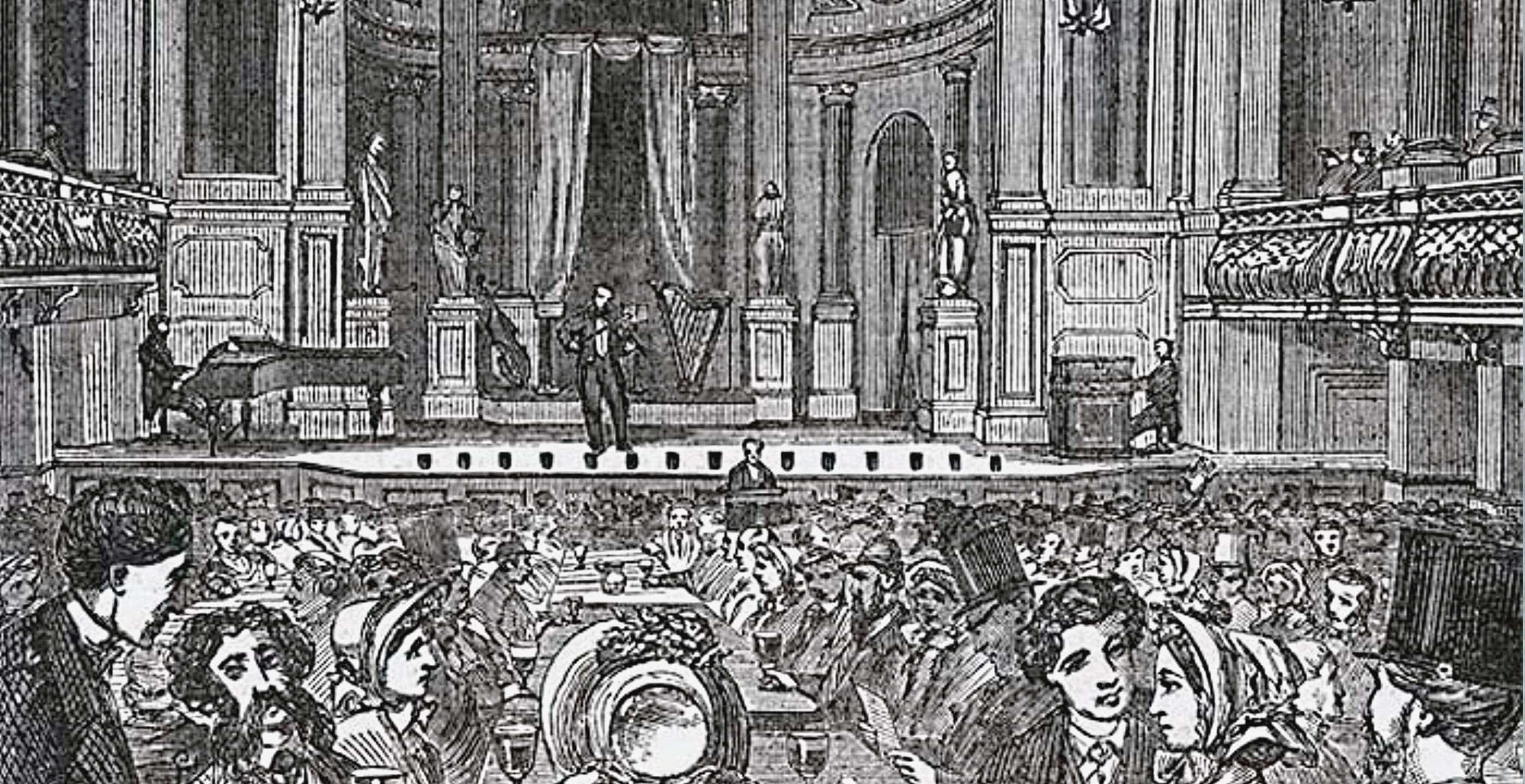

Chinoiserie represented the trend for a more fantastical imitation or reimagining of China and the East. Pantomimes such as ‘Arabian Nights’ which deployed a scattergun assortment of themes, costumes and props plucked from the figurative ‘Orient’ were wildly popular in the Victorian music halls. Decorative pagoda-style pavilions and Chinese lantern walks became ubiquitous fixtures of leisure, dotting Britain’s public parks. With the Boxer outbreak, Chinese rebels were both reviled and glamorised, incorporated into a new negotiation of Chinoiserie for the Edwardian era.

A playwright called Alfred Dawe politicised the Boxer motif by taking it literally, relating it to the sport of boxing. The rebels had engaged in Meihuaquan or ‘Plum Flower Boxing’ and calisthenics rituals that they believed granted them invulnerability to Western bullets. Baffled by this raised fist against Christian modernity, Western observers coined the nickname ‘Boxers’ to rationalise and simplify a complex crisis, giving the rebels a certain air of physical prowess in the process. Dawe clearly decided this would resonate with local audiences as he equipped his stage protagonists with oversized boxing gloves rather than the sword and bayonet, making this a central trope of the action.

According to the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays Archive, the play opened at Rugby’s Theatre Royal on 7 October 1901 as, ‘An Entirely Oriental Farcical Comedy: Sen Yamen, Or, An Overdose of Love In Two Acts’. With the music composed by Frederic William Sparrow, the broad plot arc ran as follows. ‘Chefoo’ the chief of the Boxers, and ‘Li Ching’ the local chief of police, fell in love with two women, who in turn fell in love with the wrong partner. In order win over the objects of their affection they purchased love potions. However, the scheme went horribly wrong as the women also bought love changing potions, and their affections became increasingly muddled. By the plays conclusion they decided to marry other suitors that they did not love and make the best of things.

Chefoo, one of the main characters, is depicted as strong, with large boxing gloves primed for a fight with British and Chinese alike. In the first scene alone, he knocks three boxers over in the street and hits Li Ching the policeman. The chorus chimes,

Putting heads in chancer-ee,

Hard blows and cruel knocks,

This is how we learn to box.”

As the Grandmaster of the ‘Secret Brotherhood of Bruising Boxers’, Chefoo then tries to recruit Ching into the movement, showing him the secret sign of the brotherhood. Becoming a brother, he says, means being taught how to box and having, ‘a lodge meeting once a fortnight, when by the rules we are allowed to get drunk’. Ching then endures a hot poker initiation!

Overall ‘Sen Yamen’ was a comedy, an overdose of laughter replete with mock Chinese accents that capitalised on the entanglement of ‘Boxers’ and boxing in British popular culture. Throwing together a jumble of stereotypes and ‘oriental’ props, the play engaged with the conflict’s brutality and tensions on a superficial level that sidestepped the complex rivalry between Britain and China. There were references to secret signals to ‘kick all of the interfering foreign devils out of China’, but this was as serious as the script became.

Play runs finish. Props are thrown away. Styles fall out of fashion. ‘Sen Yamen’ is a window on a moment when some chose not to take their empire too seriously. Traces of culture are often more ephemeral than statues of steel and stone, but no less valuable to investigate if we are serious about finding what kind of a raucous, vibrant, contradictory society Imperial Britain really was.

Dr. Robert Brown is a Teacher of History at the Guanghua Cambridge International School in Pudong, Shanghai. He gained his PhD in Modern British History from the University of Birmingham, UK in 2017. His research interests include Modern British History, Trans-Imperial History, and histories of race and anthropology.

Published: 4th December 2020