All modern societies owe a debt to domesticated animals. The wealth of Britain was largely established on wool and woollen products, and that is why one of the nation’s most potent symbols is still the Woolsack, the seat of the Lord Chancellor in the House of Lords. Horses, mules and donkeys provided much of the energy for Britain’s Industrial Revolution in the days before steam power.

The millions of animals who made a contribution to Britain’s economic success mostly remain nameless and unknown. Only rarely has an individual animal left a history, recorded by the humans who knew them. The tale of Old Billy, 1760 – 1822, a horse who worked for the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company until 1819 and died at the age of 62, is one of the finest examples.

Old Billy has made it into the record books as the holder of the record for equine longevity, though some sceptics have questioned whether he really did live to such an advanced age. Modern veterinary medicine and good horse welfare mean that the usual lifespan for a healthy domesticated horse is between 25 and 30 years. There are well-recorded instances from the 20th century of domesticated horses living into their 40s and even 50s, but none has ever matched Old Billy. Was he really so old when he died, or is it simply the case that the records of the time were unreliable?

The evidence for Old Billy having achieved his great age is in fact good, thanks to the appearance at the start and end of his life of the same man, Mr Henry Harrison. Old Billy was bred by a farmer, Edward Robinson, at Wild Grave Farm, Woolston, near Warrington, in 1760. Henry Harrison was 17 when he began to train Billy as a plough horse at the farm and Billy was just two years old, according to Harrison’s account.

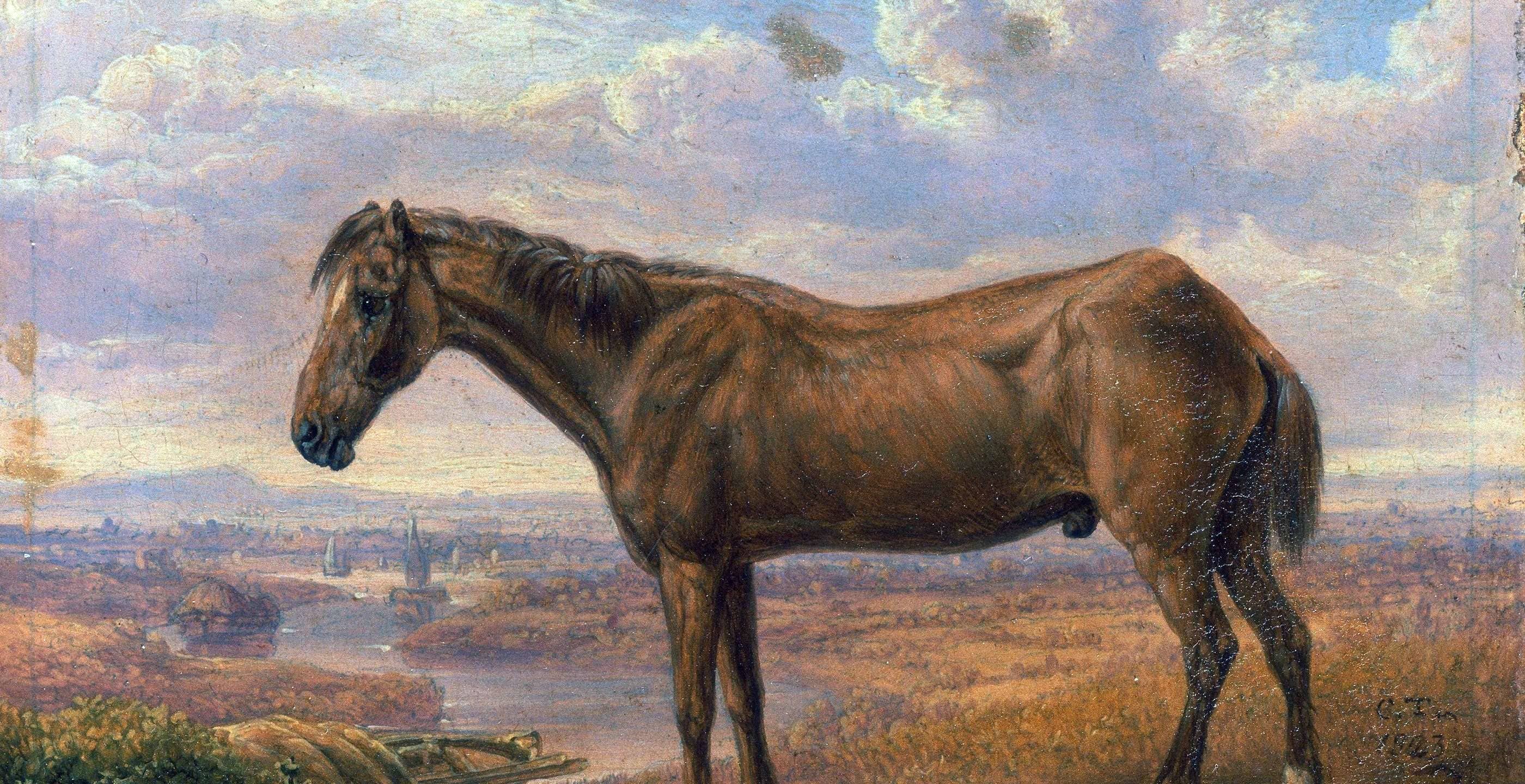

Due to his celebrity, there were various accounts of Old Billy’s life, from which it is possible to piece together the facts. He was also the subject of paintings by several 19th century artists, the best-known being Charles Towne and William Bradley. Bradley was a rising star portraitist from Manchester when he painted Old Billy in his retirement in 1821, the year before Old Billy’s death. According to one account, Old Billy was in the care of Henry Harrison then, who had been given the job by the navigation company to care for the horse as “a special charge to one of their old servants, like the horse, also a pensioner for his long service, to look after him.”

Harrison also appears in the portrait, which was engraved and used to create a number of coloured lithographs, under which was the following description: “This print exhibiting the portrait of Old Billy is presented to the public on account of his extraordinary age. Mr. Henry Harrison of Manchester whose portrait is also introduced has nearly attained his seventy-sixth year. He has known the said Horse Fifty Nine Years and upwards, having assisted in training him for the plough, at which time he supposes the Horse might be two years old. Old Billy is now playing at a farm at Latchford, near Warrington, and belongs to the Company of Proprietors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, in whose service he was employed as a Gin horse until May 1819. His Eyes and Teeth are yet very good, though the latter are remarkably indicative of extreme age.”

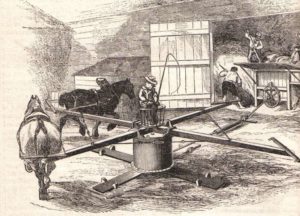

Although Old Billy has often been described as a barge horse, this may be due to the fact he was owned by a navigation company, as he is most frequently described as a gin horse in early accounts. “Gin” is short for engine, and gins were horse-powered machines which provided energy for a range of tasks, from lifting coal from coal pits to raising goods from the decks of ships, which was probably one of Billy’s jobs. The mechanism consists of a large drum encircled with a chain, to which a harnessed horse is attached via a beam. As the horse walks round and round, the energy can be transferred to pulley wheels via ropes to lift items. A similar mechanism was used to grind corn. In the north east of England, gins were known as “whim gins”, from “whimsical engines”, and this developed into “gin-gans”, because in Tyneside dialect, the “gin gans (goes) roond (round)”.

It’s possible that Billy was involved in both gin and barge work, depending on the season and the work that needed doing. He carried on working until at the age of 59, when he was retired to the estate of one of the directors of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company, William Earle. When Earle invited the artist Charles Towne to view and paint the pensioner horse in June 1822, Towne was accompanied by a veterinary surgeon, Robert Lucas and a Mr. W. Johnson who wrote a description of the horse as having cropped ears and a white hind foot. Johnson noted that the horse had “the use of all his limbs in tolerable perfection, lies down and rises with ease; and when in the meadows will frequently play, and even gallop, with some young colts, which graze along with him. This extraordinary animal is healthy, and manifests no symptoms whatever of approaching dissolution.”

In fact, this was written shortly before the horse’s death, as a note appeared in the Manchester Guardian on 4th January 1823 stating that “Wednesday se’nnight this faithful servant died at an age which has seldom been recorded of a horse: he was in his 62nd year.” (He actually seems to have died on 27th November 1822.) Johnson had also been told that until Old Billy reached the age of 50, he had a reputation for viciousness, “particularly shown when, at the dinner hour or other periods, a cessation of labor took place; he was impatient to get into the stable on such occasions and would use, very savagely, either his heels or his teeth (particularly the latter) to remove any living impediment….that happened, by chance, to be placed in his way…” Like all good workmen, he probably believed, quite rightly, that his free time was his own!

This behaviour seems to have given rise to a story that when Old Billy was supposed to take part in a Manchester celebration of the coronation of George IV in 1821 he caused plenty of trouble in the procession. He would have been 60 at the time! In fact, another, more likely story from the Manchester Guardian correspondence of 1876 says he never attended the celebration since “he was too old and could not be induced to leave the stable”. By that point he had surely earned his right to a peaceful retirement.

Old Billy’s skull is in the Manchester Museum. The teeth show the type of wear that is typical of very aged horses. It is possible that this caused him to have malnutrition, as it was noted by Johnson that Old Billy received mashes and soft food (possibly bran mashes) in the winter. His stuffed head is in the Bedford Museum, fitted with a set of false teeth to give a more authentic appearance. The ears are cropped, as in the portraits, and he has the lightning flash blaze that appears in the portraits. Old Billy’s mortal remains stand as a reminder of the millions of horses, donkeys and ponies who helped to create Britain’s wealth.